The Eastern Roots of Secularism

China’s Role in the West’s Path to Secularization

Esra Çifci

The Eastern Roots of Secularism

China’s Role in the West’s Path to Secularization

Esra Çifci

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, Christian Europe’s encounter with Confucian China exerted an influence upon the emergence of modern Europe that was no less profound than the discovery of the Americas. Yet, the Eurocentric and Orientalist historiographical tradition, formulated during the colonial era and subsequently globalized, long obscured this critical interaction from scholarly attention. The historical perspective commonly imparted from secondary education onwards presents Europe as having endured a “dark” Middle Ages under the sway of the Church until the fifteenth century, only to awaken through the twin forces of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, rediscovering reason as a guiding principle. Enlightenment thinkers, by relegating religion to the realm of theology and ritual and severing it from rational inquiry, reimagined faith as an individual, internal, and conscience-based phenomenon. In so doing, they forged secularism — the separation of religion and state — as a foundational pillar of the modern world.

Many European intellectuals pondered why secularism — the defining characteristic that distinguished modernity from classical antiquity — had emerged solely in Europe and not elsewhere. After surveying civilizations from Egypt to India to China, they attributed this phenomenon to Europe’s unique internal dynamics. From an evolutionary and progressivist standpoint, rationality was thought to have attained its fullest expression within Europe, thus enabling modernity to take root uniquely in its soil. From the sixteenth century onward, Europe’s ascendance upon the global stage unwittingly reinforced the perception of other civilizations as stagnant, inert, and incapable of genuine progress. However, beginning in the 1960’s, the rise of postcolonial scholarship dismantled Eurocentric and Orientalist narratives, rendering visible the hitherto obscured contributions of non-European civilizations to the making of modernity. A closer examination of the missionary texts produced prior to the advent of large-scale colonial enterprises reveals an even more original dynamic: these writings uncover a curious and suggestive connection between China and the secularizing impulse that reshaped Europe. Before delving into this remarkable connection, however, it is necessary to first grasp how Europe conceived of reason prior to its encounter with China.

The Definition And Conceptual Framework Of Secularism

If one were to begin with a fundamental question, it would be: What is secularism? Classical definitions typically describe secularism as the separation of church and state. Even today, if one were to ask a high school or university student, “What is secularism?”, this would likely be the response. In a broader framework, however, secularism may also be defined as the autonomization of philosophy, science, and reason from religious authorities.

Yet, when examined more deeply, it becomes clear that secularism is not confined solely to the relationship between church and state. Rather, it pertains to the process of distinguishing between the sacred and the profane realms. With the advent of secularization, religion was confined to a narrowly defined space, restricted to “theology” and acts of worship.

The reduction of religion to a matter of personal belief is a profoundly modern phenomenon. Until the sixteenth century, the global intellectual landscape knew no clear distinction between a “religious” and a “non-religious” sphere, nor any domain deemed wholly beyond the reach of religious authority.

In the modern era, with the consolidation of secularism, religion was increasingly relegated to the realm of personal faith and private ritual, while its influence over the social, cultural, and legal dimensions of daily life was progressively diminished. This transformation was, above all, peculiar to the Christian West. Yet, through the dynamics of modernity, this Western conception of secularism was universalized and imposed as a normative model across all civilizations.

At this juncture, an intriguing point warrants attention: The English term religion — used today as a general label for all systems of belief — originally emerged within the specific context of Christianity. Through the West’s secularization process, the term was generalized and applied indiscriminately to all belief systems. However, in civilizations such as China, whose cultural and intellectual structures differ markedly from those of the West, the concept of “religion” as understood in Western thought did not exist in the same form. For instance, for a Chinese thinker, the question “Is Confucianism a religion, a moral and political system, or a philosophy of life?” admits no definitive answer. In China’s intellectual tradition, the distinction between religion and culture was shaped along fundamentally different lines than in the West.

The Origins Of Secularism

It would not be an exaggeration — though it would indeed be a bold assertion — to characterize the trajectory of European intellectual history as, in part, a prolonged reckoning with Augustine of Hippo (354–430), one of the formative figures of Christian Western thought. Writing at a time when the Roman Empire was on the verge of collapse, Augustine posited revelation as the sole and ultimate truth, and argued that reason, unaided by revelation, could neither fully comprehend God nor develop a proper conception of morality. Through this vision, Augustine subordinated reason to revelation, and earthly governance to the authority of the Church, which he regarded as the temporal embodiment of divine will. While Augustine did not seek to abolish reason entirely, his primary concern lay in explaining the mysteries of incarnation and the Trinity. By embracing the doctrine of original sin and embedding it at the very heart of Christian theology, he asserted that human reason had been irreparably damaged by the Fall and was therefore incapable of attaining truth independently. This approach reinforced the supremacy of revelation, diminishing reason to a mere servant of faith, and fostered the notion that societies not illuminated by Christian revelation — including Muslims, Indians, and Chinese — were incapable of arriving at true knowledge of God and morality by reason alone. Throughout the medieval period, concepts such as paganism, idolatry, and barbarism were deployed to characterize the non-Christian world. Augustine, who laid the foundations of medieval scholasticism and shaped the trajectory of Western philosophical heritage, thus exerted an indirect yet profound influence on the course of modern secularization. In Augustine’s thought, the relationship between reason and revelation was clearly delineated. The fundamental elements of the system he constructed may be summarized as follows:

-

- The Supremacy of Revelation: Reason alone cannot attain truth; only when guided by revelation can it find the correct path without error.

- The Subordination of Political Authority to the Church: The Church, as the earthly representative of revelation, must direct political governance according to divine imperatives.

- The Exclusion of Non-Christian Civilizations: Societies lacking revelation (Muslims, Hindus, Chinese, etc.) were deemed incapable of forming a true understanding of God and morality and were thus labeled as barbaric, uncivilized, or even savage.

This mode of thought rendered the Western worldview insular and self-referential. From the sixth century onward, Europe transformed, as it were, into a “castle” encircled by towering walls. The defining characteristic of this mentality was its perception of the non-European world as pagan, idolatrous, and primitive. Indeed, this perception extended so far that, up until the sixteenth century, even Muslims were often categorized as pagans.

Even Thomas Aquinas classified Muslims as pagans and associated Islam with idolatry. This historical reality reveals that the process leading toward secularization in the West cannot be explained solely by scientific advancement or the development of rational thought. Rather, it emerged as the consequence of internal intellectual tensions within Europe and its particular gaze toward the outside world.

The revelation-centered epistemology developed by Augustine, though shaped by specific theological concerns, had a dual effect: on one hand, it drew Europe inward and precipitated the onset of the medieval period; on the other, it became one of the greatest intellectual constraints on the history of Christianity in the West. The Church, by deriving its authority from revelation, gradually consolidated power. The first serious challenge to this intellectual paradigm arose among the Latin Averroists, influenced by Andalusian thought. They posited that reason and revelation constituted two independent sources of knowledge, an idea that caused a profound rupture within medieval thought. Yet it was Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) who sought to resolve this tension. Aquinas admitted that reason, even without revelation, could attain certain truths about God and morality, though it would remain insufficient in grasping ultimate truths such as the essence of God. Thus, by establishing a balance between reason and revelation — interpreting them as complementary rather than antagonistic — Aquinas carved out a broader space for reason compared to Augustine. Unwittingly, Aquinas set into motion a fundamental shift whose reverberations would be felt not only across Europe but eventually in civilizations such as China as well.

This transformation provided the intellectual groundwork for Renaissance thinkers to accept that even non-Christian societies might, through the use of reason, make significant progress in understanding God and morality. At the same time, however, Martin Luther and his followers vehemently opposed this Thomistic openness. They accused thinkers like Aquinas of “paganizing” Christianity by placing undue trust in reason and called for a return to an Augustinian world, grounded firmly in the authority of revelation — though now proposing that reason should be entirely excluded from the realm of the Church. These debates, though intellectual in nature, soon acquired an unmistakable political dimension, intensifying the struggle between ecclesiastical and secular authorities. From the sixteenth century onward, this escalating conflict culminated in a period of bloodshed, poverty, death, plague, and widespread suffering — plunging Europe into an era of chaos and profound crisis. In response, the Catholic Church, seeking to reassert its authority and contain the turmoil, adopted a new strategy: an appeal to the infinite expanses beyond Europe. The Papacy, together with the kingdoms of Portugal and Spain, supported missionary activities alongside colonial expansion, aiming to spread Catholicism across the world, secure the obedience of foreign peoples to Rome, and profit from their resources. The reports produced by missionaries — who were the first to establish contact with diverse cultures and civilizations — simultaneously broadened Europe’s intellectual horizons and destabilized Augustine’s revelation-centered worldview, thereby laying the foundations for secular thought.

China’s Opening Doors To The Missionaries

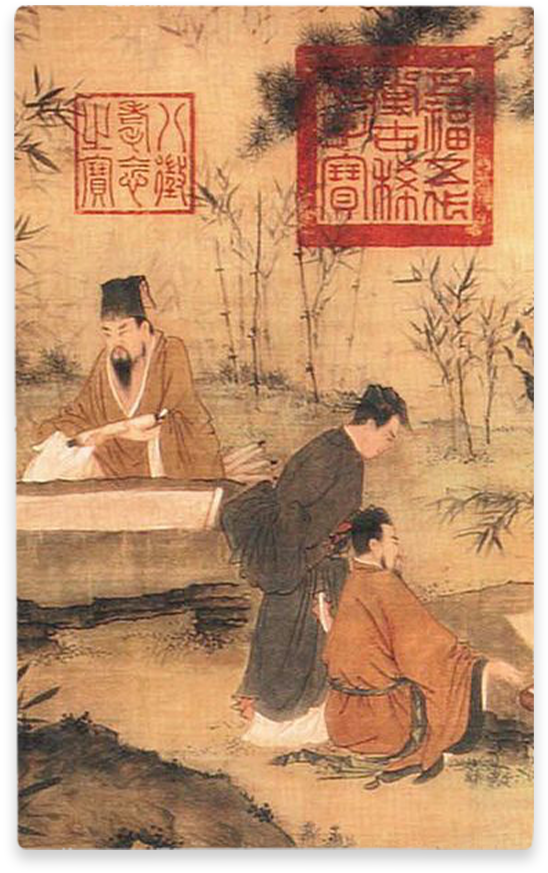

With mathematical and physical treatises intended to impress the Chinese in one hand and the Bible in the other, Jesuit missionaries boarded Portuguese colonial ships and set sail for China, making stops along the way in India, Malaysia, and Japan before finally reaching their destination. Although the peoples they encountered during their journey largely confirmed the European stereotype of barbarous and idolatrous pagans, what they found upon entering China left them astonished. The missionaries had to wait nearly forty years before gaining real access to the interior of China, during which time they were compelled to learn Chinese and present themselves as Buddhist monks.

However, after departing from an embattled Europe — a continent plagued by war, famine, pestilence, and poverty — they found themselves in the midst of vast, fertile lands, a merit-based bureaucracy, social peace, order, and stability, all of which deeply impressed and captivated them. The missionaries’ observations regarding China can be summarized as follows:

-

- China possessed extraordinary wealth.

- Unlike Europe, China was not ravaged by plagues and civil wars; instead, it exhibited a remarkable degree of social order.

- Although the Chinese were not Christians, they nevertheless lived by a highly moral code.

In their reports back to Europe, the missionaries offered a striking admonition: “If you intend to send anyone here, send only the most educated and virtuous priests. The Chinese are disciplined and morally upright people; to influence them, we must possess the highest standards of character ourselves.”

These reports marked the first moment in which Europeans were compelled to question the narrative of their own civilizational superiority. China was not, as previously assumed, a barbaric, backward, or chaotic society. At first, missionaries conjectured that the Chinese were preserving a vestige of the ancient monotheistic tradition descending from Noah. However, upon realizing that the Chinese traced their teachings not to foreign prophets but to indigenous ancestors, the missionaries were forced to account for Chinese moral and social achievements through reason alone. As Thomas Aquinas had articulated, it appeared that the Chinese, by the power of reason, had reached many truths ordinarily attributed to divine revelation — constructing a flourishing civilization without the aid of prophetic guidance.

Yet, despite their profound moral development, the Chinese conception of the divine fell short of European expectations: they believed not in a personal Creator God, but in an immanent, impersonal cosmic principle. This absence of a theistic framework deeply disappointed the missionaries. Recognizing that neither a religious nor a military conquest of China was feasible given the latter’s overwhelming superiority, Matteo Ricci adopted a strategic approach: he presented Confucianism, the foundational doctrine of Chinese governance, not as a religion but as a philosophy, and Confucius himself as a rational philosopher akin to Aristotle. He argued that the Five Classics, revered texts in Chinese tradition, could be regarded as the Chinese equivalent of sacred scriptures, and that the concept of Tian corresponded to the Christian notion of God. Practices that might seem idolatrous to a Christian observer — such as the veneration of ancestors and ritual offerings to spirits — Ricci framed as civil and political customs, rather than religious worship. In portraying China as a monotheistic, moral, and civilized “pagan” society, Ricci subtly departed from the traditional Western view that morality and culture must be rooted in divine revelation. Thus, he inadvertently laid the groundwork for a novel concept in Western thought: the idea of a secular domain independent of religion.

Ricci’s depiction of a rational, theistic China generated great excitement within the Vatican. However, missionaries who followed in his footsteps encountered a reality that diverged significantly from Ricci’s optimistic portrayal. They reported that Confucianism, the doctrine that shaped Chinese governance and society, amounted to a form of atheism or deism, while the more popular traditions of Daoism and Buddhism were characterized by elements of idolatry.

Although Ricci’s narrative was warmly received by proponents of the Thomistic (Aquinas-inspired) Catholic tradition — especially those seeking to counter Protestant critiques — its unintended consequences would only fully manifest in later centuries.

From China To Europe: The Story Of The Liberation Of Reason

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Europe’s search for an escape from the chaos and crisis engulfing the continent led Enlightenment thinkers to trace the roots of this turmoil to the subordination of reason to revelation. For deist thinkers — who argued that reason should concern itself with worldly affairs, while revelation should be confined to theology and worship — China emerged as a dangerous yet alluring example, demonstrating that morality and political order could flourish independently of divine revelation, and that reason could succeed without recourse to sacred authority. This perspective did not merely contribute to the separation of church and state; it laid the foundations for a new conceptual architecture in Europe — the separation of the sacred and the profane, the very essence of secularism.

Some missionaries dispatched to China, influenced by these unfolding debates, returned with reports asserting that the Chinese were not deists or monotheists, but atheists. Such claims provided potent arguments for Enlightenment figures like Pierre Bayle, who moved along the frontier between skepticism and atheism.

Thus, China came to represent not only the possibility of separating church and state but also the invention of a secular sphere entirely independent of religious authority — a revolutionary idea for the European imagination. In other words, China served as an inspirational model for the emergence of the distinction between the sacred and the profane realms. This conceptual shift shattered Augustine’s revelation-centered worldview, simultaneously elevating reason to a position of supreme authority. By the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, a period of admiration for the East — and especially for China — had dawned among Enlightenment thinkers. Figures such as Voltaire and Leibniz held up China as a model for Europe, emphasizing its system of governance grounded in reason and merit. Indeed, China’s example played a pivotal role in shaping Europe’s transition into the modern world. However, with the triumph of secular thought and the rise of the modern West, China’s catalytic role was gradually forgotten. The East, once a source of admiration and inspiration, was eventually relegated to the forgotten and dust-laden recesses of history, treated as little more than a tool that had outlived its usefulness.

Conclusion

Although China and Confucianism did not directly construct secular thought, they exerted an indirect yet profound influence on its realization. During Europe’s secularization process, China served Enlightenment thinkers both as a source of inspiration and as an instrument of paradigm shift. The rational and ethical orientation of Confucianism, the clear separation between religious and political spheres, the Chinese system of bureaucratic meritocracy, and the pervasive social order compelled European intellectuals to reassess their traditional Christian-centered worldview.

The observations made by Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit missionaries in China shook the theological dogmas of Europe, demonstrating that political governance and social order could indeed be constructed independently of religious authority. This realization paved the way for the rapid rise of intellectual movements such as atheism, deism, and secularism during the Enlightenment. Thinkers like Voltaire and Leibniz held up the Chinese model as compelling evidence that a society shaped by reason and virtue could thrive without dependence on religious dogma. Thus, the discourses developed through the lens of China significantly contributed to the entrenchment of key elements of the secular worldview in Europe — particularly the notions of the separation of religion and state and the existence of a non-religious public sphere.

By the nineteenth century, however, China’s role in Western thought began to fade into obscurity. Europe’s military and economic ascendancy, fueled by the Industrial Revolution, replaced earlier admiration with Orientalist and evolutionist discourses. China came to be perceived not as an exemplar of reasoned governance but as a “developing” or “backward” civilization, and the intellectual contributions it had inspired during the Enlightenment were gradually effaced from memory.

In conclusion, China’s impact on Enlightenment thought serves as a compelling example of the cross-cultural and transnational character of the history of modern ideas. The development of secularism in the West cannot be fully understood merely through the lens of internal European reforms and conflicts; it must also be situated within the context of Europe’s encounters with the outside world — especially with ancient civilizations like China. Exploring these interactions offers a powerful corrective to traditional intellectual historiography, giving voice to the long-silenced “other” and restoring to it the dignity, recognition, and historical significance it rightly deserves.

|

Esra Çifci Esra Çifci completed her undergraduate studies at the Faculty of Theology, Marmara University, between 2008 and 2012. In the same year, she began her master’s studies in the Department of History of Religions at the same university, where she prepared her thesis titled “The Emergence and Development of Confucian Muslims in the Context of Islam and Confucianism” (2015). In 2015, she commenced her doctoral studies in the field of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Marmara University. During this period, she completed a short-term internship as an assistant coordinator at the Muslim Council of Britain (2014). In 2017, she further deepened her research on East Asian religions at the International Islamic University of Malaysia. In 2018, she participated in the Researcher Training Program (AYP) at the Turkish Religious Foundation’s Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM). In 2019, she pursued one year of Chinese language education at Fudan University in Shanghai. During her doctoral studies, she examined “The Influence of Confucianism on Enlightenment Thought and Modern Western Philosophy”, and in 2024, she completed her dissertation titled “Debates on the Religious Nature of Confucianism in the 16th to 18th Centuries”. Currently, she is conducting her postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina. |

Esra Çifci

Esra Çifci completed her undergraduate studies at the Faculty of Theology, Marmara University, between 2008 and 2012. In the same year, she began her master’s studies in the Department of History of Religions at the same university, where she prepared her thesis titled “The Emergence and Development of Confucian Muslims in the Context of Islam and Confucianism” (2015). In 2015, she commenced her doctoral studies in the field of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Marmara University. During this period, she completed a short-term internship as an assistant coordinator at the Muslim Council of Britain (2014). In 2017, she further deepened her research on East Asian religions at the International Islamic University of Malaysia. In 2018, she participated in the Researcher Training Program (AYP) at the Turkish Religious Foundation’s Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM). In 2019, she pursued one year of Chinese language education at Fudan University in Shanghai. During her doctoral studies, she examined “The Influence of Confucianism on Enlightenment Thought and Modern Western Philosophy”, and in 2024, she completed her dissertation titled “Debates on the Religious Nature of Confucianism in the 16th to 18th Centuries”. Currently, she is conducting her postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina.