From Goethe to Rilke

The Conception of Prophethood and the Image of the

Prophet Muhammad in Western Poetry

Senail Özkan

From Goethe to Rilke

The Conception of Prophethood and the Image of the

Prophet Muhammad in Western Poetry

Senail Özkan

“You did not recite any book before it,

nor did you write it with your right hand.

Otherwise, the falsifiers would have

had cause for doubt.”

(Qur’ān, al-‘Ankabūt 29:48)

Interest in Islam and the Prophet Muhammad within Western literature exhibits a continuity stretching from Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan to Rilke’s prophetic poetry. Rilke, who depicted with great lyricism the moment in which revelation touches the human being, in fact found his own voice in the cultural and literary encounter initiated by Goethe through the West-östlicher Divan. Goethe, in composing this work (1819) as a poetic response to Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn Ḥāfiẓ’s Divan, opened the gates of the Islamic Orient to German letters. In this “Divan,” the “Prince of Poets” not only engaged with mythological, historical, and legendary themes of the Islamic world but also sought to grasp the religion of Islam on the plane of thought through his poetry and art. He emphasized that Muslim poets and artists were among the first to proclaim that humanity’s salvation was possible through art. In the West-östlicher Divan, Goethe gave place to the luminaries of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish literature, to distinguished thinkers and poets, poetic sovereigns and wits, composing poems in response to theirs. With this masterpiece, he not only influenced his own era but also guided later poets and intellectuals, serving as a mentor in their discovery of the hitherto little-known world of Islam and its ancient culture. Seeking to comprehend the Orient within its three-thousand-year historical formation, Goethe articulated the coordinates of his thought in the following verses:

Wer den Dichter will verstehen,

Muss in Dichters Lande gehen;

Er im Orient sich freue,

Dass das Alte sei das Neue.

He who wishes to understand the poet

Must go to the poet’s own land;

Let him rejoice in the Orient

That the Old is become the New.

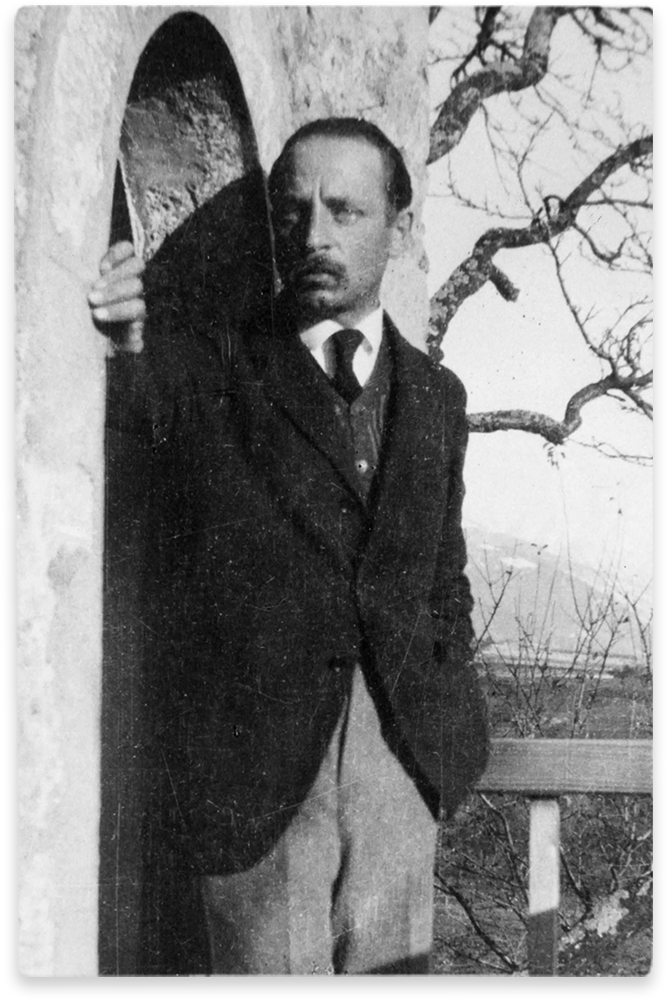

(August 28, 1749 – March 22, 1832)

(December 4, 1875 – December 29, 1926)

Believing that henceforth the West and the East were inseparably united, Goethe, through the guidance of his teacher Herder, discovered the treasures of the Orient. The Zoroastrians from three thousand years prior, their Magian priests, the Prophet who conveyed Islam to humanity one thousand four hundred and thirty-two years before Goethe’s own birth, the Muslims, Persian, Arab, and Ottoman poets, dervishes, and witty sages—all these captivated Europe’s wise poet. In his own land, however, he was deeply wearied by the political upheavals, unending crises, and social tensions that gripped Europe. Thus, one day he suddenly found himself beneath the dizzying starry sky of the Orient. His poem entitled Hegira is a product of these Oriental airs; it is a testament to the poet’s imaginative “migration to the pure East.” Indeed, Goethe had already, as a flamboyant youth, been enamored of the Qur’ānic narratives. His Mahomed’s Gesang (The Song of Muhammad) reflects the genius’s vision of the Prophet of Islam. With extraordinary sensitivity, he portrays the Prophet’s life journey through the metaphor of water and flow: a clear spring bursting forth from the rocks, swelling into a mighty river of unity, and rushing toward the ocean. This lengthy qasīda begins as follows:

Look at the spring of joy,

bursting forth from the rocks,

like the sudden flash of a star;

its youth was nourished

by exalted spirits above the clouds,

in a grove among the cliffs.

…

The West-östlicher Divan ranks among the most creative and influential works born of contact with the faith and intellectual system of another religion, and with a foreign culture, literature, poetry, art, and philosophy. This work complements Faust much like the contraction and expansion of the heart in systole and diastole. Civilizations and cultures become aware of their own powers and limits only through encounter with other cultures; thought and art are fertilized, enriched, and strengthened by such exchanges. Without this contact—which requires both courage and sincerity—our intellectual and spiritual life cannot flourish; it risks instead becoming barren and shallow. This principle holds true for nearly all traditions of thought and culture. In this sense, Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan constitutes an extraordinarily bold and creative initiative. One may even say that Goethe’s sincere endeavor generated a wave that prepared the ground for new waves of thought. Poets and thinkers such as Hofmannsthal, Hesse, Rilke, and Muḥammad Iqbal stand as powerful representatives of this current, carrying the tradition across continents. At times, when one encounters how closely some of these poets’ sentiments and modes of thought resemble those of Goethe—occasionally even drawing upon the same metaphors—one cannot help but be struck by the affinity.

As noted earlier, Goethe portrayed the Prophet Muhammad and his blessed journey through the metaphor of water. What is truly striking is that, one hundred and sixty years later, Rilke—the great lyrical voice of Europe—expressed his admiration for the Prophet with the very same image:

Muhammad, in every respect, was the nearest; like a river cutting its course through the ancient mountains, he made his way toward the One God—toward a God with whom, each morning, one could converse in wondrous intimacy, without the need for that so-called ‘Christ’ who functions as a telephone intermediary, always asked ‘Who is there?’ yet never providing an answer.

Rilke, by temperament, was a cosmopolitan poet; his perception and faith were open to all cultures and religions. Although the roots of his thought allowed him to grasp Christian culture in all its depth, he was never fully reconciled with Christianity. There were many elements within this religion and its cultural manifestations that he found alien and even repellent. For instance, he had no fondness for Gothic architecture. By contrast, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, with its architecture and ribbed interior arches, enchanted him. In a letter written from Seville on December 4, 1912, to Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis, Rilke openly condemned the devastation left by the Christian conquest of Andalusia, laying it bare with a candor that reads almost like a moral indictment:

[…] Toledo escaped with only minor losses, even Córdoba itself. That mosque—yet what has been made of it! The structure built within it is a grief, a sorrow, a disgrace: those churches squeezed into its ribbed interior, one longs to comb them out like knots from beautiful hair. Chapels thrust into the darkness like heavy masses, whereas the space itself was attuned to receive God unceasingly, gently, like the juice dissolving from a ripening fruit. Still, to hear the sound of the organ and the responses of the choir of priests in that space was utterly unbearable (qui est comme le moule d’une montagne de Silence [as though molded from a mountain of silence]). Unwittingly, one could not help but think: Christianity was continually slicing God as one cuts a beautiful cake, whereas God is whole, God is complete.

By contrast, Rilke’s attitude toward Islam was marked by attentiveness, interest, and respect. He always referred to the Prophet Muhammad with deep reverence, and spoke with admiration of the Qur’ān, which he read with great curiosity. During his visit to Córdoba, he wrote on December 17, 1912, to Princess Marie of Thurn und Taxis, confessing with fervor:

You must know this, Princess: since Córdoba I have been in an almost aggressive opposition to Christianity; I am reading the Qur’ān, and at times it speaks to me with such a voice that I feel myself wholly within it, like the wind within an organ. Here one imagines oneself still in a Christian country, but that already lies far behind…

The very next day, he wrote another letter, this time to Lou Andreas-Salomé:

[…] Here I am reading the Qur’ān and I am astonished, utterly taken aback; once again, I feel in myself a tremendous eagerness and desire to learn Arabic […].

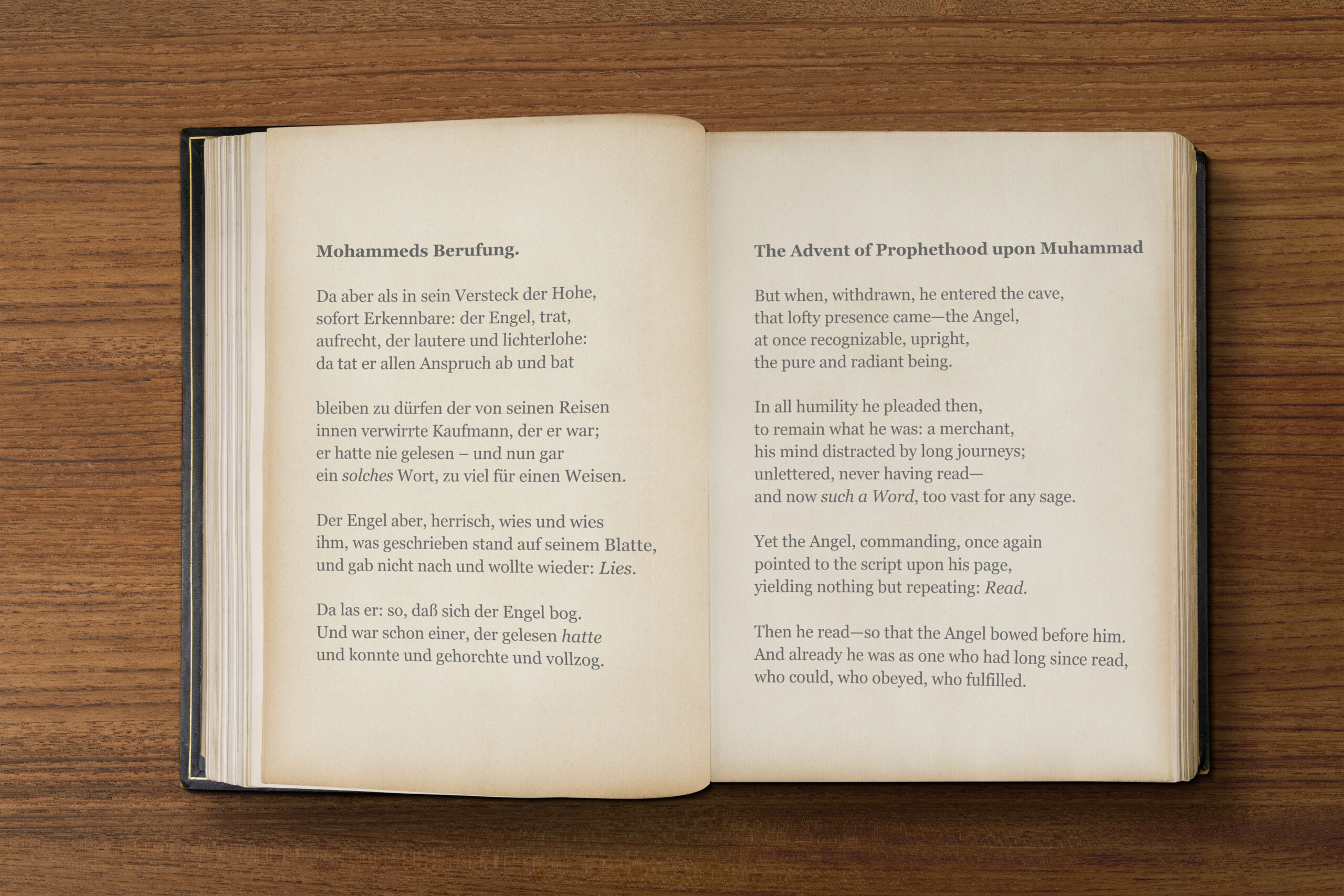

Yes, this ‘tremendous desire’ for the Qur’ān and for the Arabic language would, over the years, turn into an admiration for the Prophet Muhammad, eventually inspiring Rilke to compose this magnificent sonnet in which the Prophet’s words are reflected as if upon the inner mirrors of his heart. With extraordinary poetic sensitivity, Rilke portrays in this sonnet the advent of prophethood bestowed upon Islam’s exalted Messenger. The sonnet is presented here in its German original alongside my translation:

Now, let us consider why this poem is significant and what it conveys. First of all, from where does Rilke’s affinity or sympathy for Islam, its sacred scripture the Qur’ān, and the Prophet Muhammad arise? When we look into Rilke’s life story, we see that he had various points of contact with the cultural geographies of Islam. The poet was born in the city of Prague; his homeland was the old Austria, where he grew up, a land that functioned as Europe’s gateway to the Orient. We should not forget that the great Ottoman historian and renowned Orientalist Hammer von Purgstall was Austrian, and that the poet and Orientalist Friedrich Rückert—celebrated as the “storehouse of rhyme”—studied with Hammer. Rückert, moreover, was a remarkable translator who succeeded in rendering the Qur’ān into German with fidelity to its didactic style and even to its rhythmic cadence.

During his early years as a budding poet, when he began his university studies, Rilke became acquainted with and later befriended Lou Andreas-Salomé and her husband, the famous Persian philologist and Orientalist Friedrich Karl Andreas. They played a decisive role in nurturing Rilke’s interest in and sympathy for the world of the Orient and the culture of Islam. On his travels to Russia with Lou Andreas-Salomé, Rilke not only met Tolstoy but also encountered Muslim communities there, engaging with them directly. Though episodic, these encounters left an impression upon him and fostered a sympathy toward Muslims.

At the same time, through the encouragement and guidance of Professor Andreas, the Persian philologist, Rilke read translations of the Qur’ān, through which he formed a partial understanding of Islam and its Prophet, an understanding that over the years gradually deepened.

Rilke’s poem “The Advent of Prophethood to Muhammad” (Mohammeds Berufung) is included among the Neue Gedichte (New Poems), written between 1903 and 1908. We know that during this period Rilke served as secretary to the sculptor Rodin, and in his own words, he “learned to see” from him—for in virtually every branch of art, the secret of creativity lies in the act of seeing. What is meant here by “seeing” is not mere looking, but rather prolonged contemplation (temāshā), watching with intuition, penetrating into the essence of things, grasping their inner nature, and discerning the defining character of the artistic object. For Rilke, this form of contemplative seeing was so essential to artistic creation that he would later declare: “Yes, everything that is truly beheld must become poetry!” The criterion of Rilke’s poetic vision is this: if a poet can objectify human states and experiences through the medium of language—turning them into a “thing”—then he is truly a poet. The poems Rilke wrote employing the creative method he learned from Rodin the sculptor and Cézanne the painter, he himself classified under the category of “thing-poems” (Dinggedichte).

Having thus outlined, in general terms, Rilke’s conception of poetry, his poetic vision, and the perspective from which he approached creativity in artistic phenomena, we may now return to the poem at hand—his “The Advent of Prophethood to Muhammad.”

This poem, evidently composed to exalt the Prophet Muhammad, is cast in the sonnet form, the most frequently employed poetic structure in the West. The reason for Rilke’s particular choice of this form lies in the sonnet’s extraordinary aptitude for depiction. Indeed, from beginning to end, the poem is governed by description. With an exceptional sense of temāshā (contemplative vision) and deep emotional intuition, Rilke interiorizes and renders visible the event of prophethood’s arrival to Muhammad. Yet this perception and depiction are of such intensity that the one who describes and the one described seem to have merged into one. While the poem recounts the Prophet’s reception of prophethood in fidelity to the Qur’ānic narrative, the boundaries between the lyrical “I,” the Prophet himself, and the angel of revelation, Gabriel, are dissolved, and before our eyes language gives rise to a “work of art,” an “art-object.” As Gabriel summons the Prophet with the imperative “Read!” the lyrical subject assumes the role of a witness.

The poem’s rhyme scheme, its interplay of half and full rhymes, the linking of the two quatrains by means of enjambment, its alliterations, shifting emphases, and structural irregularities all confer upon the sonnet—so widely used in European poetry—a new and distinctive perfection. Yet our concern here lies less with form than with content.

In this context, I cannot refrain from emphasizing the following: anyone with even a modest sensitivity to poetry will inevitably encounter, while reading the sonnet, numerous pauses and stylistic devices that slow down its flow, producing certain formal dissonances. These, however, are not accidental; they are elements consciously employed by the poet to reflect the inner tension the Prophet Muhammad experienced at that moment. Indeed, as a result of these pauses, the rhythm of the poem grows heavier, generating a profound and hesitant effect upon the reader. Yet it must be remembered that this very effect corresponds precisely to the atmosphere of the prophetic event itself, and in this respect the poet achieves an extraordinary fidelity.

Briefly stated, the event depicted in the poem is this: while the Prophet Muhammad was in retreat and contemplation within the Cave of Ḥirāʾ, the angel of revelation, Gabriel, appeared before him and began to deliver the divine message. To the command of God’s messenger, “Read!”, the Prophet responded, “I do not know how to read.” At Gabriel’s insistent command—spoken with the force of divine authority—the Prophet at last complied: he repeated what had been taught to him, and thus recited the revelation. What the poet here seeks to depict, as is well known, is none other than the moment of prophethood’s advent as narrated in the Qur’ān, in Sūrat al-ʿAlaq: “Recite in the name of your Lord who created! Created man from a clot. Recite! For your Lord is Most Generous—He who taught by the pen, taught man what he knew not.”

As the Qur’ān further indicates in Sūrat al-ʿAnkabūt (29:48), the Prophet—who was unlettered, that is, unable to read or write—became the recipient of divine knowledge and inward illumination through his acceptance of revelation.

It is well known that Plato declared, “Knowledge is in truth the recollection of that which was known before creation.” In this sense, the poet is here reminding us of the primordial covenant (bezm-i elest) between humanity and God. According to this covenant, Muhammad recalls the pledge made before creation, the “Ancient Agreement” between man and God: “And [mention] when We raised the mountain above them as if it were a canopy, and they thought it would fall upon them, [and We said]: ‘Hold firmly to what We have given you and remember what is in it, that you might become righteous’” (al-Aʿrāf 7:171). Being fully aware of these theological resonances, Rilke alludes to this knowledge in the second tercet of his sonnet, particularly in its second line.

“Und war schon einer, der gelesen hatte…”

“And already he was as one who had read…”

In the first two quatrains of the sonnet, the Prophet Muhammad—who, before receiving prophethood, would at times withdraw to the cave on Mount Ḥirāʾ for prayer and contemplation—is depicted as “weary and distracted,” gripped by fear when the angel of revelation suddenly appeared before him. Yet, once Gabriel conveyed the divine message, a radical transformation takes place: Muhammad assumes the mantle of prophethood, and the dynamic between messenger and recipient is dramatically altered. The angel who had first appeared in an imperious posture now bows before the Prophet, for authority has passed to him. The Prophet is henceforth endowed not merely with human knowledge but with divine knowledge that surpasses all earthly wisdom. The final line of the second quatrain,

“ein solches Wort, zu viel für einen Weisen”

“Such a word, too much even for a sage,”

alludes to the divine Word, the speech of God Himself. After becoming the Messenger, Muhammad now bears within him knowledge beyond the realm of human comprehension; he is entrusted with the mission of conveying God’s Word. In other words, the consciousness and imagination that had until then been like a tabula rasa—a blank page—begin to be filled with the verses of God, with the influx of divine knowledge. This, in truth, is the climax of the poem. At this point, Rilke captures with profound sensitivity the Prophet’s inner struggle in the presence of God, transforming his own poetic diction into a field of struggle over words themselves. He succeeds in reflecting this tension within his verses, elevating the sonnet into a lyrical re-enactment of revelation’s drama.

In the first two quatrains of the sonnet, the mounting tension gradually gives way—through a shift in perspective—to what may be called a “song of descent” in the second half of the poem. In the tercets, the flame of words diminishes and the intensity subsides in nearly every line. The Prophet Muhammad’s sincere, humble, and defensive posture in the second quatrain undergoes, so to speak, a radical transformation after Gabriel issues the command “Read!” in the final line of the first tercet. When the Prophet, after a strenuous struggle, succeeds in reading—that is, when he accepts revelation—he acquires a station higher than that of the Angel, Gabriel, who until then had been the commanding figure. Thus the Angel bows before the Prophet who had once appeared defensive and humble.

Another striking feature of the poem is the shift in tense. In the second tercet, the verse

Da las er: so, daß sich der Engel bog

“Then he read—so that the Angel bowed before him.”

is expressed in the simple past, but soon after, in the line

Und war schon einer, der gelesen hatte

“And already he was as one who had read,”

the verb moves into the past perfect. In this way, the Prophet is not confined to the immediacy of earthly time; rather, by implication, there is an allusion to the bezm-i elest—the primordial covenant—expanding the horizon of his knowledge into the depths of pre-existence.

Likewise, in the final verse of the sonnet,

und konnte und gehorchte und vollzog

“He was able, and obeyed, and fulfilled,”

the act of “fulfilling” is projected into the future. The poem thus remains open-ended, directing the reader toward the future mission and actions of the Prophet.

It becomes evident, therefore, that before receiving prophethood, Muhammad was known as one who influenced people by his own trustworthy speech, being called al-Amīn (“the trustworthy”). After accepting prophethood, however, he no longer spoke by his own words but by the divine Word—the revealed verses—through which not only human beings but even the angels were drawn into his sphere of influence, bowing before him.

|

Senail Özkan Senail Özkan was born on October 21, 1955, in Gümüşhane, Turkey. He began his studies in Electronic Engineering at Hacettepe University in 1974, but in 1978 he left for Germany, where between 1979 and 1985 he studied philosophy, German literature, and sociology at the University of Bonn. Returning to Turkey in 1998, Özkan has since pursued his career as a philosopher, writer, and translator. Among his authored works are: Mevlâna and Goethe (2006), Nietzsche: Philosophy on the Tiger’s Back(2004), Schopenhauer: Dance upon Paradoxes (2006), Love and Reason: East and West (2006), Philosophy of Death (2013), Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan (2009), The Sorrows of Young Werther (2014), Faust (2022) His translations include: Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall’s Istanbul and the Bosphorus I (2011), Katharina Mommsen’s Goethe and Islam (2012), Goethe and World Cultures (2015), Annemarie Schimmel’s On the Roads with Yunus Emre (1999), I Am Wind, You Are Fire (1999), Muhammad Iqbal (2007), The Oriental Cat (2009) For his translation of Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan, Özkan received the Translation Prize of the Turkish Writers’ Union in 2009. In recognition of his contributions to Turkish culture through both translation and original works, he was also awarded the Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Prize by Star newspaper in 2015. |

Senail Özkan

Senail Özkan was born on October 21, 1955, in Gümüşhane, Turkey. He began his studies in Electronic Engineering at Hacettepe University in 1974, but in 1978 he left for Germany, where between 1979 and 1985 he studied philosophy, German literature, and sociology at the University of Bonn. Returning to Turkey in 1998, Özkan has since pursued his career as a philosopher, writer, and translator.

Among his authored works are: Mevlâna and Goethe (2006), Nietzsche: Philosophy on the Tiger’s Back(2004), Schopenhauer: Dance upon Paradoxes (2006), Love and Reason: East and West (2006), Philosophy of Death (2013), Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan (2009), The Sorrows of Young Werther (2014), Faust (2022)

His translations include: Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall’s Istanbul and the Bosphorus I (2011), Katharina Mommsen’s Goethe and Islam (2012), Goethe and World Cultures (2015), Annemarie Schimmel’s On the Roads with Yunus Emre (1999), I Am Wind, You Are Fire (1999), Muhammad Iqbal (2007), The Oriental Cat (2009)

For his translation of Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan, Özkan received the Translation Prize of the Turkish Writers’ Union in 2009. In recognition of his contributions to Turkish culture through both translation and original works, he was also awarded the Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Prize by Star newspaper in 2015.