Karagöz, Sufism, and Music

in the Ottoman Empire

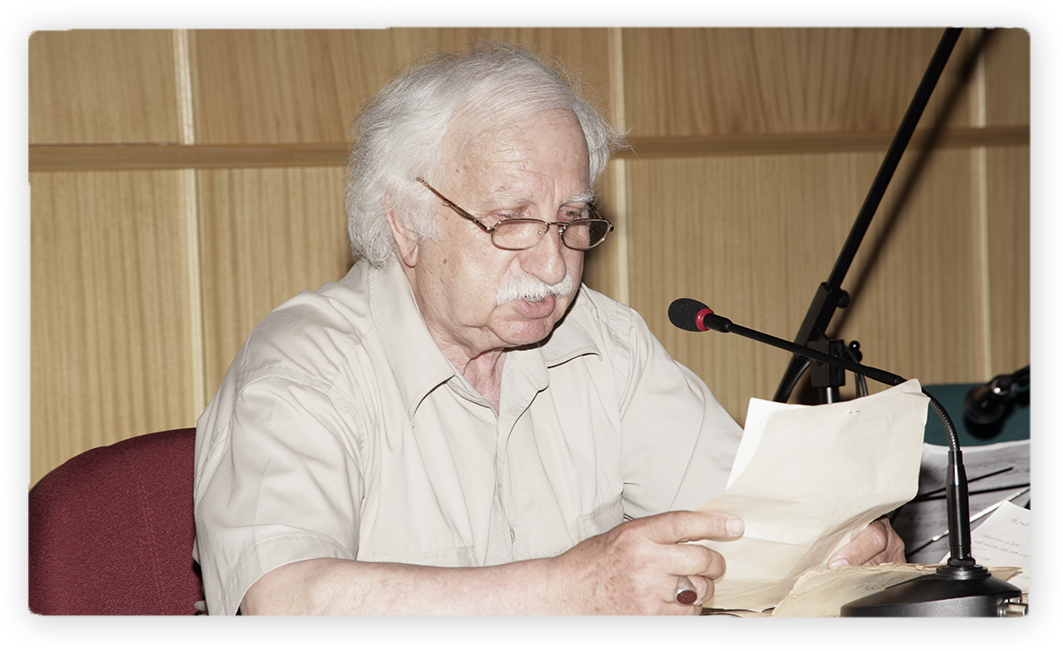

In Memory of Kutbünnâyî Niyazi Sayın

Niyazi Sayın

Karagöz, Sufism, and Music in the Ottoman Empire

In Memory of Kutbünnâyî Niyazi Sayın

Niyazi Sayın

İSAM – July 1, 2005

Transcription: Arzu Güldöşüren

Honourable audience, I stand before you not with a formal lecture but rather with an informal conversation. Although my primary field is music, my modest involvement with several other traditional arts has led me to engage in various areas to the extent of my ability, and this pursuit has continued in what might be called a “from cradle to grave” understanding. We had earlier decided to organize a talk bringing together Karagöz, Sufism (tasavvuf), and music. For this reason, I would like to speak briefly about Karagöz, its connection with Sufi thought, and music.

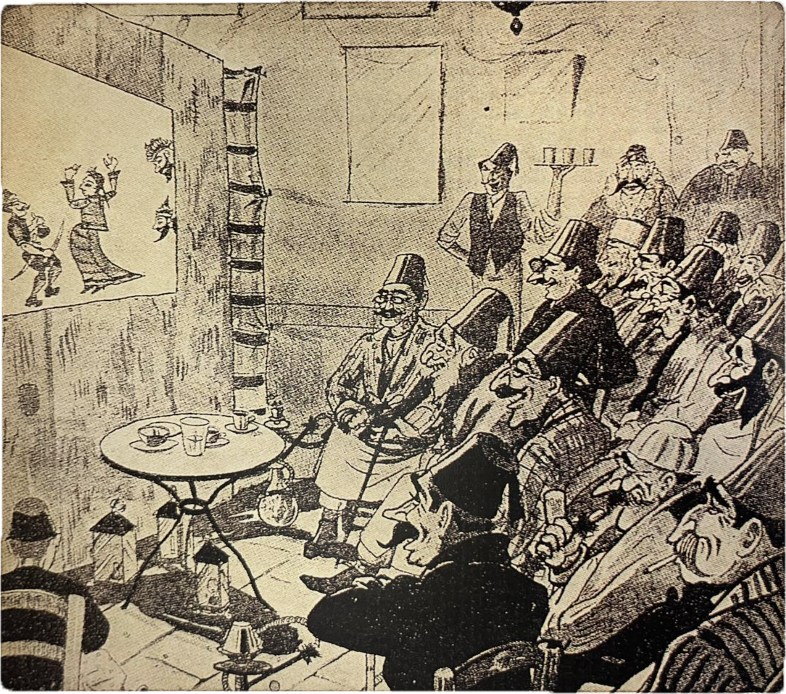

Karagöz is a theatrical system found within the cultural structures of many nations. Some assert that it came from China; others claim that it emerged in the Ottoman lands beginning from the time of Sultan Orhan. However, according to existing research, it is said to have been present in China two centuries before the Common Era, and four centuries ago in India. Each nation has its own form of the Karagöz system—its own variety of shadow-play. In this way, these peoples found the opportunity to present their manners, literature, history, and musical traditions through this form of performance. As you know, in our own tradition the appearance of the Karagöz play is associated with an event that took place in Bursa during the time of Sultan Orhan, and thus it is understood that Karagöz emerged from Bursa. Over time, the play reached such a level of development that it became a theatrical system addressing various segments of daily life. During the period in which a certain Bedir Sıdkı Dede—a man who had undertaken the Mevlevî çile (the Mevlevi novitiate) in Konya—was undergoing his spiritual retreat in the lodge, a letter arrived from “Nemse” (Austria). Since no one knew the Nemse language, they sought assistance from various people. Eventually, Bekir Sıdkı Dede stated that he knew the language and could read the letter. The matter was presented to the Çelebi (the head of the Mevlevi order). The Çelebi summoned him into his presence and had the letter read aloud. Sıdkı Dede declared that he had come into the presence of Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, that he had entered the Mevlevi novitiate, and that he also served as a mesnevîhân (reciter and interpreter of the Mathnawī). In accordance with this state, the Çelebi officially recognized him as a mesnevîhân and entrusted him with this duty. A single manuscript leaf written by this individual has survived to the present day. He was also trained as a calligrapher (hattāt). I shall now present it to you exactly as it appears.

Hayâl(Shadow-Play) and Karagöz

Among the havas (the learned and refined classes) the performance was known as “Hayâl,” whereas among the avam (the common people) and sıbyan (children) it was called “Karagöz.” This play was performed within the bounds of propriety and decorum, and particularly when the performer himself belonged to the class of zurefâ (cultivated gentlemen), it became, in every respect, an occasion for contemplation and admonition. Indeed, when viewed with an eye of discernment (çeşm-i ibret), there exist even fatwas issued by reliable scholars (sikāt) such as Fenârî and Ebüssuûd permitting the viewing of the hayâl performance; the following extract (kıṭ‘a-i âtiyye) is derived from a fatwa of Mevlânâ Fenârî. In accordance with its reputation among the people, this play is said to have been devised from the perspective of representing divine unity (temsil-i vahdet), and its originator is reported to have been a man of refined knowledge, Shaykh Küşterî, who is buried on Government Street (Hükümet Caddesi) in Bursa. According to transmitted reports, during the reign of Yıldırım Bayezid Han, two witty figures—Hacı İvaz and Hacı Evhad, known in the vernacular as Hacivat and Karagöz—had their humorous debates (münazaralar) presented upon the shadow screen (perde-i hayâl) by Shaykh Küşterî, thus bringing the play into being.

In the Seyahatnâme of Evliya Çelebi, beginning on page 654 of the first volume, he recounts, in a manner bordering on fantastical exaggeration, numerous reports concerning the mel‘abe-i hayâl (shadow-play). According to these accounts, Hacivat was a courier (sâî) who lived during the reign of ʿAlâeddin of the Seljuk dynasty, traveling between Mecca and Bursa, and was killed by desert bandits (eşkıyâ-yı urbân), being buried at Bedr-i Huneyn. Karagöz, on the other hand, is said to have come from Kırkkilise and served as a courier to Emperor Constantine. Their dialogues were performed on the shadow screen by Kör Hasan, one of the witty performers (nekregû) among the refined imitators (zurefâ-yı mukallidîn) of the reign of Yıldırım Bayezid Han, and thus enacted in the presence of Bayezid Han himself. However, in a work attributed to a noble scholar named Imâm al-Shaʿrânî, it is stated—quoting from chapter 317 of al-Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn al-ʿArabî’s al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya—as follows: “Whoever desires to know that God, exalted be He, is truly the freely acting agent (fāʿil-i muḫtār) behind the veil of creation, let him look upon the forms displayed through the veil of shadow (hayâl-i sitâre).” In the same section it is explained in detail that children become absorbed in the mel‘abe-i hayâl, while the spiritually mature (ahl-i vakt) extract subtle meanings from it. Considering that the death of al-Shaykh al-Akbar (638/1240) predates that of Shaykh Küşterî, it becomes evident that this play was already known among the Arabs of al-Andalus—the original homeland of Ibn al-ʿArabî—under the name sitâre. In any case, the cultivated and refined (zurefâ-yı urefâ) have composed numerous delicate allegories concerning this play and have written many poems. Among these, it is noted that the grave of Karagöz may be seen in Bursa, near the resting place of the venerable Süleyman Dede, the celebrated composer of the Mevlid-i Nebevî, on the right side of the road.

Such a work is indeed extant in our possession. I now present to you the views of Bekir Sıdkı Dede concerning Karagöz.

Before the performance begins, and likewise in the middle of the play as well as at its conclusion, there are poetic passages composed in verse, which I wish to draw to your attention. These are beautiful compositions bearing a Sufi character. I would like to read one or two of them for you.

The veil of vision reflects, as a symbol, the beauty of Divine craftsmanship;

The veil of truth belongs to the Master of the Decree from pre-eternity.

In outward form it is possible to behold the inward reality;

The veil of insight places no obstacle before the eye of gnosis.

Whatever you look upon with faith becomes manifest and clear;

The veil of heedlessness has cast its shadow upon the entire world.

The true art lies in surveying this world of forms like a passing shadow;

Countless darkened eyes have been effaced by the veil of appearance.

The flame of love burns away the form of the body portrayed upon the screen;

The veil of departure renders the human being a traveler on the path of return.

Whichever shade you seek refuge in, it strangely never perishes;

Behold the master who moves the puppets—he has set up a veil of affection.

Remain steadfast, O Kemterî, at the threshold of the House of the Cloak (Āl-i Abâ);

For as the veil of multiplicity is lifted, the hand of unity becomes apparent.

I draw your particular attention to this final couplet:

“Remain steadfast, O Kemterî, at the threshold of the House of the Cloak;

For as the veil of multiplicity is lifted, the hand of unity becomes manifest.”

I shall read one more piece.

To the outward-looking eye this screen is but an image of form;

Yet for the people of symbols it is the very representation of truth.

Shaykh Küşterî set up this screen in resemblance to the world;

What attentiveness he displayed in likening each form to its kinds.

Its spectacle bestows joy upon those who seek delight;

While for those who behold reality, it is the very eye of admonition.

No one knows what lies beyond the veil—this is the matter established;

Through the tongue of state, it narrates the condition of the world.

Should one look carefully upon Karagöz and Hacı Evhad,

Those who grasp their meaning perceive an entirely different state.

How many subtle meanings there are to be considered beneath its surface;

It is offered with courtesy so that people of discernment may understand its witticisms.

When the candle is extinguished the figures of form vanish at once;

This is a sign of the world’s impermanence and lack of abiding.

Now I shall present to you a passage from the Dîvân of Mehmet Ali Baba, one of the sheikhs (babas) of the Merdivenköy Bektashi Lodge in the later period, who had a prayer-platform (namazgâh) constructed at the lodge’s outer gate and spent his time between the mosque and the tekke. It is a beautiful perde gazeli composed for Karagöz; I shall now read it.

Upon the banquet of existence is set the veil of wisdom’s shadow;

It displays, from pre-eternity, the veil of power fashioned by Divine artistry.

The purpose is that the wise may draw a lesson from the tale;

Though Karagöz performs the play, this is truly the screen of admonition.

The One who causes the inner and outer worlds to be traversed

Is the Artisan Himself—the veil of vision makes this evident to the eye.

Every soul that comes and goes within the realm of forms

Manifests its own deeds upon the veil of manifestation.

Cast a single gaze upon essence and form in the realm of meaning,

So that the veil of unity may be unveiled to you in its secret.

It is the Light of Truth that renders visible every shadow beyond the screen;

The Eternal Master has set the veil of form upon the plane of appearance.

Be a devotee of the House of the Cloak (Âl-i Abâ), O Hilmî, in truth and constancy;

For from the Gate of Ali the veil of union with God is opened.

In our musical tradition, great value has also been attributed—particularly in terms of güfte (lyrics)—to the works of Nakşî-i Akkirmânî Ali Efendi (d. 1065/1655), a figure belonging to the Khalwatiyya order (Tarikat-ı Halvetiyye). Many poets have benefited from his compositions, and composers have likewise drawn upon them. Indeed, in the Arazbar and Bayatî-Araban modes—especially in Bayatî-Araban—there is a well-known hymn beginning with the line “Eyâ sen sanma kim senden bu güftârı dehân söyler,” which you may be familiar with. I now present to you the perde gazeli written by this same master.

Do not suppose that these words are spoken by your mouth,

Nor that they are uttered by the elements combined or by the flesh of the tongue.

Wishing first to make you known unto yourself, the Lord intended such,

And having clothed you in a garment of the elements, He speaks through your outward form as His interpreter.

The shadow-image upon the tent of the body is sufficient as an admonition;

It is not the visible form that speaks, but the One who resides within.

Those who know not the self and have taken no lesson from “Know thyself,”

Are not the true knowers of God; they speak falsehood without knowing their own essence.

Whose are these countless movements, whose is the jewel that speaks?

If you have not attained knowledge of your own essence, then it is not you but another source that speaks through you.

He created all things, concealing His own essence within them;

Though He appeared through a thousand forms, He Himself remains hidden as the One speaking.

“Their Lord shall give them to drink”—O Nakşî, those lovers who drink this wine

Reach their Beloved, and they speak beyond place, from non-spatial realms.

In verse 72 of Sūrat al-Aḥzāb, there is a manifestation of the dignity and worth that God, exalted be He, has bestowed upon us; yet while it is incumbent upon us to recognize that worth, one of the masters among the people of God (ahlullāh) interprets the phrase “innahū kāna ẓalūman jahūlā” as indicating that, when we look into the mirror, we are unable to perceive our own mysteries and our own beauty, and thus live deprived of Divine truth and of the Messenger of God. Likewise, in verse 23 of Sūrat al-Shūrā, God expresses to us a matter of fundamental importance: “Qul lā as’alukum ‘alayhi ajran illā al-mawaddata fī al-qurbā”. I am not a ḥāfiẓ; if I make an error, you will surely pardon me. Here, the meaning is: “I ask of you no recompense—save that you show love (mawadda) toward my near kin (qurbā, i.e., the Ahl al-Bayt).” This love, this mawadda, is of great significance and must be reflected upon. It is an injunction commanded to us by God Himself, so that we may cultivate this love for the Ahl al-Bayt. Indeed, at the conclusion of the perde gazeli in the Karagöz repertoire, the poets too have embedded this very philosophy by emphasizing love for the Ahl al-Bayt. There are many more verses concerning this matter, and it would be beneficial for us to reflect upon them with due attention. There are numerous definitions of taṣawwuf in the scholarly tradition: being with God, becoming purified from all that is other-than-God (sivā), and similar expressions—many of which appear in hymns and devotional compositions. For my part—and I prefer to speak concisely—I understand the essence of taṣawwuf as “love for the Messenger of God, living one’s life continuously with the desire to understand him, to live with him, and to live by his example.” Many hymns and musical compositions—religious and non-religious—express this meaning. This state is also reflected in the Karagöz performance. In the version performed for children, these notions do not appear; however, in the Karagöz performed for the havas and the urefâ, this philosophy is always present. You will appreciate that a Karagöz performance presented in the presence of the sultan cannot resemble one staged for children. Our musicians have rendered great service to the Karagöz tradition; today, we possess notated versions of approximately two hundred and ten thousand pieces associated with Karagöz. We know that works by major composers such as Dellâlzâde İsmâil Efendi (d. 1286/1869), Hamâmîzâde İsmâil Dede Efendi (d. 1846), Ebûbekir Ağa (d. 1172/1759), Buhûrizâde Mustafa Itrî Efendi (d. 1123/1711), and ʿAbdülkādir-i Merâgī (d. 838/1435) were performed within Karagöz plays. Within these performances, musical forms such as pişekâr havaları, kavuklu havaları, zenne havaları, Acem havaları, Kayseri havaları, muhacir havaları, and similar pieces—each associated with specific characters who appear on stage—were composed by our master musicians. With the emergence of highly skilled Karagöz performers—particularly in the Ottoman period—the tradition was maintained with refinement, though later, around the time of Karagözcü Kâtip Salih, it began to decline somewhat. We have learned from venerable figures whom we deeply respect—men of great spiritual worth—that masters such as Müştak Baba and Karagözcü Ömer Efendi performed Karagöz with a distinctively Sufi mode and meaning.

I do not wish to detain you any further. This is all I have to say concerning Karagöz, Sufism, and music. I would prefer not to take more of your time and to leave you now to the music itself. I extend my thanks for your kind attention.

References

Balıkhane Nazırı Ali Rızâ Bey. Eski Zamanlarda İstanbul Hayatı. Nşr. Ali Şükrü Çoruk. İstanbul: Kitabevi, 2001.

Uzun, Mustafa İsmet (ed.). Meşrûtiyet’ten Cumhuriyet’e Yakın Tarihimizin Belgesi 1908-1925 Sırâtımüstakim Mecmuası. İstanbul: Bağcılar Belediyesi, 2013.

Mehmed Ali Hilmi Dedebaba. Mehmed Ali Hilmi Dedebaba Dîvânı. Nşr. Gülbeyaz Karakuş. İstanbul: Revak Kitabevi, 2012.

|

Niyazi Sayın (12 February 1927 – 8 October 2025) He was born in Üsküdar, Istanbul. He completed his primary and secondary schooling in Üsküdar Paşakapısı and began his high-school education in Haydarpaşa and Beyoğlu, though he was unable to continue due to the economic circumstances of the post-war period. His acquaintance with Mustafa Düzgünman in 1947 marks the beginning of his involvement with traditional Ottoman-Turkish arts and ney training. He commenced his first ney lessons on 4 March 1948 with Gavsi Baykara; from 21 January 1949 onward he pursued regular meşk sessions with Halil Dikmen for nearly fifteen years. In the 1950’s he served as a ney performer for the Istanbul Radio Music Broadcasts. Between 1956 and 1969 he was a member of the Performing Ensemble (İcra Heyeti) of the Istanbul Municipal Conservatory. After 1976 he taught at the Istanbul Technical University Turkish Music State Conservatory as an instructor and served within the Department of Wind Instruments (Nefesli Sazlar Anabilim Dalı). In 1980 he taught Turkish music within an educational program at Seattle University in the United States. His artistic activities beyond music included work in ebru (marbling), photography, and various forms of traditional craftsmanship. Sayın was awarded the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Grand Award for Culture and Arts in 2009 and the Presidential Grand Award for Culture and Arts in 2014; through both his repertoire contributions and the performance techniques he developed, he is regarded as one of the principal figures shaping the modern ney tradition. He passed away in Istanbul on 8 October 2025. His funeral was held on 10 October 2025 at the Valide-i Cedid Mosque in Üsküdar, after which he was interred in the burial ground of the Sandıkçı Şeyh Edhem Baba Lodge (tekke). |

Niyazi Sayın

(12 February 1927 – 8 October 2025)

He was born in Üsküdar, Istanbul. He completed his primary and secondary schooling in Üsküdar Paşakapısı and began his high-school education in Haydarpaşa and Beyoğlu, though he was unable to continue due to the economic circumstances of the post-war period. His acquaintance with Mustafa Düzgünman in 1947 marks the beginning of his involvement with traditional Ottoman-Turkish arts and ney training. He commenced his first ney lessons on 4 March 1948 with Gavsi Baykara; from 21 January 1949 onward he pursued regular meşk sessions with Halil Dikmen for nearly fifteen years.

In the 1950’s he served as a ney performer for the Istanbul Radio Music Broadcasts. Between 1956 and 1969 he was a member of the Performing Ensemble (İcra Heyeti) of the Istanbul Municipal Conservatory. After 1976 he taught at the Istanbul Technical University Turkish Music State Conservatory as an instructor and served within the Department of Wind Instruments (Nefesli Sazlar Anabilim Dalı). In 1980 he taught Turkish music within an educational program at Seattle University in the United States. His artistic activities beyond music included work in ebru (marbling), photography, and various forms of traditional craftsmanship. Sayın was awarded the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Grand Award for Culture and Arts in 2009 and the Presidential Grand Award for Culture and Arts in 2014; through both his repertoire contributions and the performance techniques he developed, he is regarded as one of the principal figures shaping the modern ney tradition.

He passed away in Istanbul on 8 October 2025. His funeral was held on 10 October 2025 at the Valide-i Cedid Mosque in Üsküdar, after which he was interred in the burial ground of the Sandıkçı Şeyh Edhem Baba Lodge (tekke).