A New Understanding of Sīrah

Glimpses from the Blessed Life

Ahmet Özel

A New Understanding of Sīrah

Glimpses from the Blessed Life

Ahmet Özel

The significance of the Prophet Muḥammad (peace and blessings be upon him) in Islam lies not merely in his conveying of the divine message to humanity. As expressed in the Qur’ānic verse, “Indeed, in the Messenger of Allah you have an excellent example for whoever hopes in Allah and the Last Day and remembers Allah often” (al-Aḥzāb 33:21), his importance also resides in the fact that he personally embodied how the ideal of the insān-i kāmil (the perfected human) presented in this message could be realized in life. Through the entirety of his being—his thoughts, conduct, and inner disposition—he established the measure for both the deepest spiritual life and the most complete social order. When ʿĀʾisha (may Allah be pleased with her) was asked about the character of the Messenger of Allah, she replied, “His character was the Qur’ān itself,” a statement that perfectly conveys this truth.

Since he was sent as a guide to all humankind—whose characters, moral inclinations, and temperaments differ—he was endowed with a spiritual and intellectual maturity sufficient to address the personal and social needs of all people and to lead them aright. Yet, despite these divine endowments, the Prophet lived as a human being among other human beings; he possessed no superhuman traits that would remove him from the realm of human imitation. Were it otherwise, his life could not serve as a perfect model for humanity, as the Qur’ān declares. Indeed, his being the only prophet and leader known to have successfully applied the ethical, legal, political, and social principles he proclaimed throughout human history is a direct consequence of his role as a human exemplar and guide.

The life of the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) represents harmony and balance amid the complex web of human existence—among social, political, economic, and even sensual desires that no one can master without transcending the limits of mere human weakness. He was, at once, a prophet, a statesman, a leader, a commander, a judge, a teacher, a merchant, a head of family, a father, a neighbor, a friend, and even, at times, a dignified adversary; in all these dimensions, he offered an exemplary model to humanity in both material and spiritual realms.

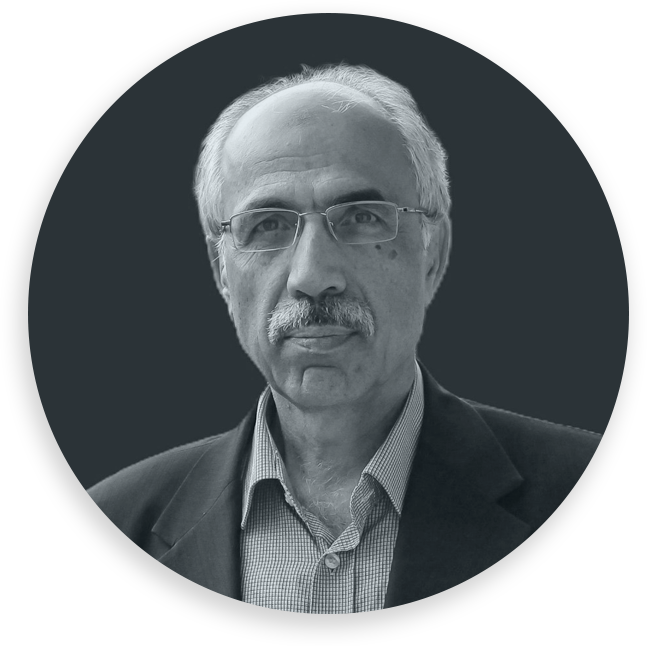

The ta‘liq calligraphic Hilye-i Şerif panel by Hulûsi Efendi

(from the Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi calligraphy collection)

The biographical and ḥadīth sources that record his life thus present not merely historical data but a lived exposition of the Qur’ānic vision. They reveal how the divine message was reflected in concrete existence and made manifest as an example to others. Early sīrah compilations, though characterized by simplicity, realism, and restraint from exaggeration, nevertheless contained, albeit rarely, certain legendary narratives, miraculous reports, and Isrāʾīliyyāt-type materials whose historical authenticity is highly doubtful. In subsequent centuries, the religious, intellectual, and socio-political circumstances of various authors led some to alter or embellish the existing sīrah corpus—out of excessive love for the Prophet, in an effort to elevate him beyond human measure, or to provide doctrinal support for their own ideological positions. Such tendencies gradually made the task of discerning authentic accounts increasingly difficult. As a natural result of this process, historical reality was often replaced by literary imagination: the Prophet Muḥammad came to be viewed less as a model to emulate and more as an object of affection and veneration. Consequently, he ceased to be the subject of history and became instead the subject of art and literature, around which a vast devotional culture and a rich variety of literary genres eventually developed.

From the nineteenth century onward, under the influence of the rationalist and positivist spirit of Western science and the expanding field of Orientalist studies, a new era began within the sīrah tradition, alongside other branches of Islamic scholarship. In addition to the traditional Western polemical approach—largely characterized by distortion, fabrication, and defamation toward Islam and the Prophet Muḥammad (peace be upon him)—there also emerged, during this period, a number of Orientalists who sought to examine the Prophet’s life on the basis of the earliest Islamic sources. Their critical analyses of the data found in sīrah and ḥadīth collections gave rise to extensive debates, particularly concerning the authenticity and reliability of these materials. While some Orientalists attempted to cast comprehensive doubt on all sīrah and ḥadīth literature, others adopted a more moderate stance, arguing that by applying certain critical methods it was still possible to identify sound information within these sources and to reconstruct a trustworthy portrait of the Prophet.

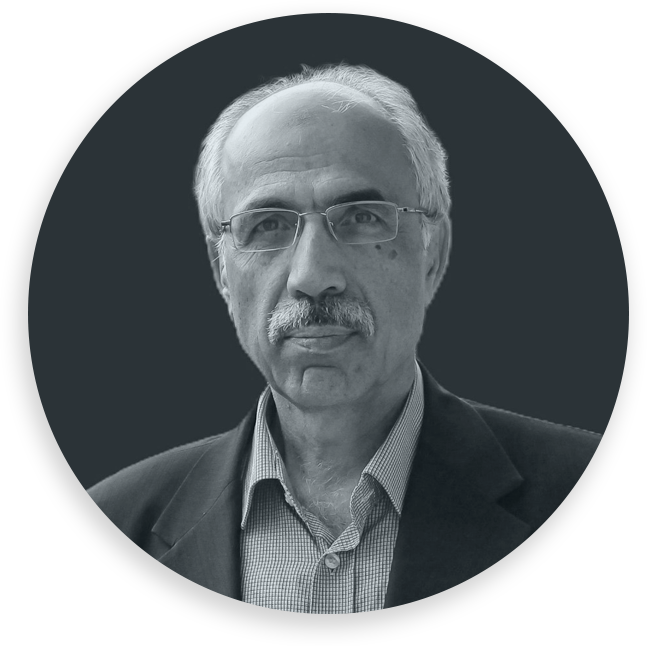

At Ahmet Özel’s study desk in the İSAM Library

Some of these works were soon translated into Eastern languages and began to resonate within Muslim societies that were themselves undergoing profound transformations under Western influence. The intellectual and social life of these societies—shaped by the military, political, and economic dominance that Western scientific and technological advancement had made possible—entered a period of introspection, reform (iṣlāḥ), revival (iḥyāʾ), and renewal (tajdīd). Within this context, a new phase of the sīrah tradition took form.

From India to Turkey and Egypt, numerous scholars, despite variations in style and approach, undertook efforts to reinterpret the Prophet’s life in its authentic historical context—stripped of legendary tales, miracle narratives, and popular embellishments. Relying instead on the Qur’ān, authentic ḥadīths, and verified sīrah reports, they sought to re-present the Prophet as a preacher, moral reformer, and social activist who transformed his society through the moral and spiritual force of his message.

As in the past, Muslims across different regions and cultures continue today to compose works about the Prophet, seeking to understand and introduce him anew. Naturally, these writings reflect the intellectual climates and cultural sensibilities of their respective contexts, producing diverse conceptions and literary expressions of the Prophet’s image. What must always be safeguarded, however, is that such portrayals emerge strictly from sound and authoritative sources, in full harmony with the spirit of the Qur’ān and the authentic Sunnah, so that the image of the Prophet as both the Messenger of God and the perfect human being (al-insān al-kāmil) is presented faithfully.

It is impossible to comprehend or convey how the Prophet transformed his society—within scarcely a quarter of a century—from its former religious, intellectual, social, and political state solely by relying on narratives woven entirely of miraculous accounts. The key to understanding him, and to cultivating a sound conception of prophethood in the minds of believers, lies within the framework set by the Qur’ān itself. Indeed, the Prophet’s transformation of his community in accordance with the divine message he preached constitutes an unparalleled achievement in human history—one that, by itself, suffices to demonstrate his truthfulness as the Messenger of God. As early scholars such as al-Jāḥiẓ, al-Māturīdī, and Qāḍī ʿAbd al-Jabbār observed, his very life stands as a miracle in its own right.

Just as a person who recites the Qur’ān daily may one day, after months or even years of reading, suddenly perceive a verse as if struck by lightning—its meaning penetrating the folds of the mind and depths of the heart—so too may one who studies the life of that exalted Messenger, who transmitted this divine message and fully absorbed it into his own being, experience moments of spiritual awakening. One may find oneself astonished by a single act, word, or gesture of the Prophet and exclaim: “Such a thing could never be conceived, spoken, or done by an ordinary human being!” Those who observed him closely—his noble Companions—were repeatedly moved by such moments, their admiration for the Messenger of God deepening each time. Likewise, as a reader seeks to enter into the life of the Prophet, the Prophet’s life begins to enter into the reader—enveloping the soul, illuminating the heart, and bringing serenity and peace. Yet, to partake in the spiritual grace (barakah) of both the Qur’ān and the noble Messenger who conveyed it, one must approach them with sincerity and without prejudice. Only a heart purified of ulterior motives and animated by genuine devotion can truly perceive the radiance of the Prophet’s example.

In what follows, a number of striking and evocative instances will be presented—episodes from the life of the Messenger of God that touch the heart, enlighten the spirit, and reveal glimpses of the moral beauty that transformed humanity.

Forgiveness and Clemency

Hebbâr b. Esved, of the Banū Asad branch of the Quraysh, had lost his brothers — ʿAkīl b. Asved, Zamʿa b. Asved, and Zamʿa’s son Ḥārith b. Zamʿa — at Badr. Hebbâr had been among the foremost opponents of Islām, lampooning the Prophet and the Muslims in his poetry. About a month after the Battle of Badr (2/624), upon learning that the Prophet’s daughter Zaynab was travelling from Mecca to Medina, he and Nāfiʿ b. Abd al-Qays set off in pursuit. At Zūtuwa, on the way out of Mecca, their thrusting of a lance frightened the caravan’s camel; Zaynab fell onto a rock, suffering a fractured rib and losing the child she was carrying — an injury whose pain she felt for the remainder of her life. On account of this incident the Prophet dispatched a detachment and ordered that Hebbâr and Nāfiʿ be apprehended and put to death; but the party returned without finding them. Hebbâr later figured among the ten men who had been sentenced to death when Mecca was to be captured, yet he could not be apprehended at that time either. Some time afterwards, however, Hebbâr resolved to embrace Islām. He came to the Prophet after the distribution of the spoils at Hunayn, when the Prophet had just returned to Medina from Jirāna. Seeing him in the Prophet’s presence in the Masjid an-Nabawi, some of the Companions — aware of the earlier death-sentence against him — immediately informed the Messenger that this man was Hebbâr; some among them rose as if to attack him. The Messenger of Allah, however, gestured for them to be seated. Hebbâr then addressed the Prophet, saying: “Peace be upon you, O Messenger of Allah. I testify that there is no god but Allah and that you are His Messenger. I fled from you from place to place, thinking to take refuge in foreign lands; then I recalled your kindness to your relatives, your nobility, and your forgiving disposition toward those who had treated you ignorantly and coarsely. O Messenger of Allah, we were a people of idolatry; by your means Allah guided us, by your agency He delivered us from ruin. Forgive me for the rudeness I committed against you — I confess my wrongdoing and acknowledge my sin.” Thereupon the Messenger replied, “I have forgiven you; by guiding you to Islām Allah has conferred a favour upon you. Islām erases the sins committed before it.” Zubayr b. ʿAwwām reported: “I was looking at the Prophet. Seeing Hebbâr’s contrition for his deeds, the Prophet humbly bowed his head and said, ‘I have forgiven you!’”

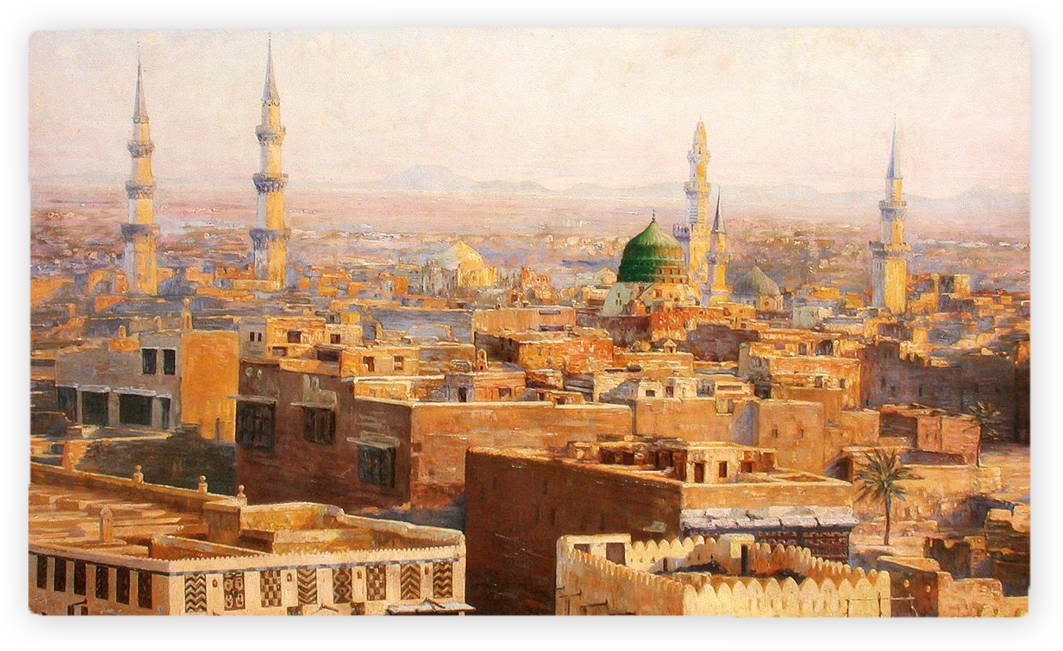

An oil painting depicting Medina in the late 19th century

Although the general amnesty granted at the conquest of Mecca extended to the Meccans at large, Ikrimah b. Abū Jahl was listed among the ten men who had been condemned to be put to death had they been captured. Ikrimah fled — at one point attempting to throw himself into the sea to die (or seeking to escape to Yemen) — and made for the port of Shuʿaybah. On the day of the Conquest his wife, Umm Ḥakīm bint Ḥārith, embraced Islām and requested that the Prophet show clemency to her husband. Acting upon her intercession, the Prophet forgave Ikrimah; his wife sought him out and, finding him by the shore or on board a ship, persuaded him to return to Mecca together. When Ikrimah arrived, the Prophet admonished the Companions not to curse his father; then, seeing Ikrimah, he rose with joy, embraced him and exclaimed, “Mounted migrant, welcome!” When Ikrimah asked what the Prophet was inviting him to, the Prophet reminded him of the essentials: faith in the oneness of Allah, prayer, almsgiving, and the other pillars of Islām. Ikrimah responded, “By Allah, you invite us only to good and to virtuous deeds! Even before you called us to that which you now call us, you were our most truthful speaker and most benevolent among us. I testify that there is no god but Allah and that Muḥammad (peace and blessings be upon him) is His Messenger.” He then requested that the Prophet pray to Allah for forgiveness for all the enmities he had borne, the campaigns in which he had opposed the Muslims, the encounters in which he had faced them, and all the words he had spoken, either to their faces or behind their backs. The Messenger of Allah enumerated these petitions and supplicated to the Exalted for his pardon. Thereupon Ikrimah declared: “I am content, O Messenger of Allah! Whatever I spent to hinder the way of Allah I will spend in His path in like measure; for whatever battles I joined to oppose the way of Allah, I will henceforth fight in His cause.”

Among the captives taken at the Battle of Badr was Suhayl b. ʿAmr, one of the most prominent notables of Mecca and a fierce opponent of Islam. He was also the cousin of the Prophet’s wife, Sawda bint Zamʿa. It was Suhayl who had signed the Treaty of al-Ḥudaybiyyah on behalf of Quraysh. Because of his eloquence and his frequent speeches against the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb once said, “O Messenger of Allah, allow me to pull out his two front teeth, so that his tongue will hang out and he will never again speak against you.” The Messenger of Allah replied: “No, ʿUmar. I will not mutilate him. Were I to do such a thing, even as a Prophet, Allah would do the same to me. Perhaps a day will come when he will stand in a place that will please you.” Indeed, Suhayl b. ʿAmr embraced Islam either at the conquest of Mecca or soon after the Battle of Ḥunayn (6 Shawwāl 8 AH / January 630 CE). When the Prophet (peace be upon him) passed away, Suhayl stood before the people of Mecca and delivered an address similar to the one Abū Bakr gave in Medina, calling the believers to composure and steadfastness. When many Arab tribes began to apostatize following the Prophet’s death, some Meccans, too, were on the verge of abandoning the faith. The city’s governor, ʿAṭṭāb b. Asīd, had gone into hiding out of fear. At that moment, Suhayl stood at the door of the Kaʿbah and declared: “O people of Mecca! You were the last to accept Islam—do not be the first to turn away from it! By Allah, the Almighty will surely complete this religion, just as His Messenger foretold. I heard him say, while standing right here: ‘Say with me, Lā ilāha illā Allāh (There is no god but Allah), and by your testimony the Arabs will embrace Islam and the non-Arabs will pay jizyah to you. By Allah, the treasures of Chosroes and Caesar shall be spent in the path of Allah!’ Some people mocked him, and others believed him. You have seen his words come true—by Allah, the rest will also be fulfilled!” Hearing these words, the people calmed down, and the governor came out of hiding. When ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb learned of this, he remembered the Prophet’s earlier words about Suhayl and exclaimed: “I bear witness once again that you are truly the Messenger of Allah!”

The place where the Battle of Badr took place

(Saudi Arabia)

It is also reported that Abū Bakr (may Allah be pleased with him) later said: “No conquest in Islam was greater than the Peace of al-Ḥudaybiyyah. People did not comprehend what passed between the Messenger of Allah and his Lord. Servants hurry, but Allah, exalted is He, is never hasty; He ordains matters in their proper time. During the Farewell Pilgrimage, I saw Suhayl b. ʿAmr holding the sacrificial camels as the Messenger of Allah slaughtered them with his own hands. I saw him summon his barber and have his hair cut, and Suhayl hastened to collect some of the blessed hair and apply it to his eyes. At that moment, I remembered how, at al-Ḥudaybiyyah, he had refused even the writing of the Basmala (In the Name of Allah, the Most Merciful, the Compassionate), and I praised Allah who had guided him to faith.”

Jubayr b. Muṭʿim, whose uncle Ṭuʿaymah b. ʿAdī had been slain at Badr, promised his Abyssinian slave Vahshī freedom if he would kill the Prophet’s uncle, Ḥamza b. ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, in revenge. During the Battle of Uḥud (3/625), Vahshī fulfilled this grim commission. He extracted the liver of the martyred Ḥamza and brought it to Hind bint ʿUtbah, the wife of Abū Sufyān, whose father, uncle, and brother had all been killed at Badr. In her fury, Hind took a piece of the liver into her mouth and chewed it, then rewarded Vahshī with her ornaments and fashioned necklaces and anklets for herself from the severed noses and ears of the martyrs.

After killing Ḥamza, Vahshī returned to Mecca and remained there until its conquest five years later, when he fled to Ṭāʾif. When a delegation from Ṭāʾif later travelled to the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) to embrace Islām, Vahshī, fearing for his life, considered escaping to Syria, Yemen, or elsewhere. At that moment, someone said to him, “Woe to you! Muḥammad does not kill anyone who enters his religion.” Encouraged by these words, he went to Medina, appeared before the Messenger of Allah, and recited the testimony of faith. The Prophet asked him, “Are you Vahshī?” When he replied, “Yes,” the Prophet had him sit down and said, “Tell me how you killed my uncle.” After Vahshī recounted the event, the Prophet (peace be upon him) said, “Woe to you! Do not appear before me again!” Out of deep shame, Vahshī withdrew and never appeared before him thereafter.

When news reached the Prophet that Vahshī had arrived in Medina, he said, “Leave him unharmed. For me, the embracing of Islām by a single soul is dearer than the killing of a thousand unbelievers.” During their conversation, when Vahshī confessed that his deed was nearly tantamount to disbelief, the Prophet recited the verse: “Indeed, Allah does not forgive association with Him, but He forgives whatever is less than that for whom He wills.” (al-Nisāʾ 4:116). Still uneasy, Vahshī said that although the verse spoke of Allah forgiving whomever He willed, he did not know whether he himself could be forgiven. Then the Messenger of Allah recited another verse: “Say, ‘O My servants who have transgressed against themselves, do not despair of the mercy of Allah. Indeed, Allah forgives all sins. Truly, He is the All-Forgiving, the Most Merciful.’” (al-Zumar 39:53).

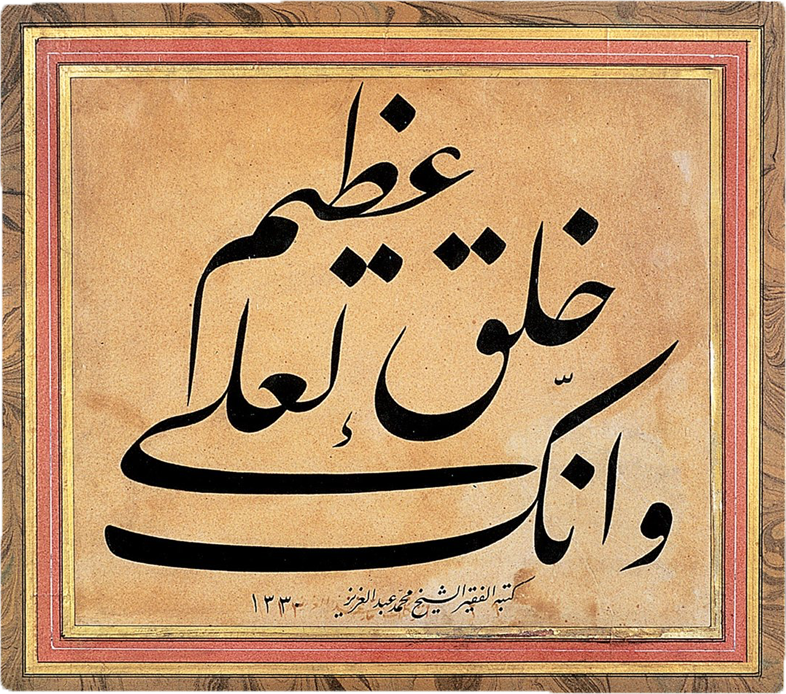

A composition of the Qur’anic verse praising the Prophet (Qur’an, al-Qalam 68:4), written in jālī ta‘liq script by Aziz Efendi

(from the Muhittin Serin collection)

His Humility

In the month of Rabīʿ al-Ākhir of the ninth year after Hijra (July–August 630 CE), the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) dispatched a detachment under the command of ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib to destroy the idol known as Fuls (Fels), located on Mount Ajā along the Mecca–Syria trade route, some 500 kilometers northwest of Medina. The tribal chief, ʿAdī b. Ḥātim al-Ṭāʾī, fled with his family into the Syrian lands inhabited by Christian Arabs. During the ensuing clash, several members of his tribe were captured and brought to Medina, among them ʿAdī’s sister, Ṣafānā. Ṣafānā, a woman of intelligence and eloquence, was brought before the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) and pleaded: “O Muḥammad, release us, that we may not become a tale on the tongues of the Arab tribes! I am the daughter of my people’s chief. My father was a man who protected the sacred trusts of honor, who freed captives, fed the hungry, clothed the naked, hosted guests, provided food, greeted all, and never turned away a petitioner. I am the daughter of Ḥātim al-Ṭāʾī.” Hearing this, the Prophet replied: “O young woman, these are the attributes of a true believer. If your father had been a Muslim, I would have prayed for Allah’s mercy upon him.” He then ordered, “Release her, for her father loved noble character (makārim al-akhlāq), and Allah loves noble character.”

Later, when Ṣafānā informed the Prophet that she had found a caravan with which she could safely return home, he provided her with new garments, a riding animal, and the necessary provisions for her journey. Upon reaching Syria, Ṣafānā went to her brother ʿAdī and reproached him, saying: “O oppressor who severed the bond of kinship! You fled with your wife and children but abandoned your father’s trust and honor!” ʿAdī acknowledged her rebuke and apologized. He then asked, “What do you think of this man?” Ṣafānā replied: “By Allah, I believe that you should go to him and join him without delay. If he is indeed a Prophet, then to reach him early is a virtue and an honor. So-and-so went to him and found his share, and another went to him and found his share. But if he is merely a king, then you will lose nothing of your status in Yemen—you are who you are, and your father is who he was; your dignity is known.” ʿAdī said, “By Allah, this is a sound opinion indeed!” Thus, in the month of Shaʿbān of that same year, he set out with his family for Medina. When he entered the mosque, he saw the Prophet (peace be upon him) seated with a woman and one or two children whom he was attending to. “Then I knew,” said ʿAdī later, “that he was not a Kisrā or a Qaysar (an emperor or a king).” After introducing himself, the Prophet took him to his home. On the way, they encountered an elderly and frail woman, and the Prophet stopped to tend to her needs with gentleness and care. Witnessing this, ʿAdī said to himself, “By Allah, this man is no king!” When they reached his house, the Prophet insisted that ʿAdī sit on a leather cushion, while he himself sat upon the ground. Again ʿAdī thought, “By Allah, this is not the behavior of a king.” They then conversed at length, during which ʿAdī’s heart was opened to the truth and he embraced Islām.

That No One Has Assurance of the Hereafter

ʿUthmān b. Maẓʿūn, one of the earliest and most devout Companions, was so zealous in worship that at one point he considered having himself castrated in order to renounce worldly desires entirely. He fasted continually by day and spent his nights entirely in prayer, to the distress of his wife, who eventually complained to the Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings be upon him). The Prophet summoned ʿUthmān and said to him:

“Have I not been given to you as a beautiful example? I live with women, I eat meat, I fast and I break my fast. The celibacy (tabattul) of my ummah is fasting. Whoever castrates himself is not of my community!” In another narration, the Prophet advised him, saying: “Your eyes have a right over you, your body has a right over you, and your wife has a right over you. So pray—and also sleep; fast—and also break your fast.” ʿUthmān later became the first of the Muhājirūn (Emigrants) to die after the Battle of Badr. As his body was carried to the grave for burial, the Prophet (peace be upon him) said in praise: “You have departed—and you were untouched by this world.” Yet when ʿUthmān’s wife exclaimed, “O ʿUthmān, how fortunate you are! You have entered Paradise!” the Prophet, displeased, asked: “How do you know this?” She replied, “O Messenger of Allah, he was your companion and your close friend!” The Prophet then said: “By Allah, even though I am the Messenger of Allah, I do not know what will be done with me!” In another narration, a woman once declared with certainty about the deceased Companion Abū al-Sāʾib: “O Abū al-Sāʾib, may Allah’s mercy be upon you! I testify that Allah has honored you!” The Messenger of Allah asked her: “And how do you know that Allah has honored him?” She replied, “May my father and mother be ransomed for you, O Messenger of Allah! I do not know—but if a man like him has not been honored, then who would be?” The Prophet responded: “As for him, he has now met with the truth. By Allah, I hope for good for him—but even though I am the Messenger of Allah, I do not know what will be done with me.”

His Refusal to Distinguish Himself from Those Under His Command

Immediately after the Hijrah, when the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) undertook the construction of the Masjid al-Nabawī, he himself laid the first stone of its foundation. The sources relate that the Prophet not only encouraged his Companions to work but also carried building materials alongside them, reciting verses with them as they labored. According to his freedman Zayd b. Ḥārithah, when one of Medina’s notables, Usayd b. Ḥuḍayr, attempted to take the stone that the Prophet was carrying, the Prophet said to him, “Take another one; you are no more in need of Allah’s grace than I am.”

The Prophet’s attitude of sharing in the labor, refusing to exempt or distinguish himself from others, was repeatedly demonstrated on various occasions, particularly during the Battle of the Trench (Khandaq, 5/627). Before the battle, he was frequently seen coming out of his tent to dig with his Companions and to carry earth upon his blessed shoulders. Al-Barāʾ b. ʿĀzib described the scene: “I never saw anyone more beautiful than the Messenger of Allah. His complexion was bright, his hair was thick and flowed to his shoulders, and on that day I saw him with the earth upon his back.” Abū Saʿīd al-Khudrī likewise said: “I was watching the Messenger of Allah as he worked with the Muslims in digging the trench; dust covered his chest and abdomen.” On one occasion, after long hours of digging and breaking rocks, the Prophet grew tired, leaned against a boulder, and fell asleep. Abū Bakr and ʿUmar stood beside him, keeping people from disturbing his rest. When he awoke, he leapt to his feet and said, “Should you not have woken me?” Then, without delay, he returned to the work.

At the Battle of Badr, the Muslims numbered 313 (in other reports 310-319), and they possessed only seventy camels and two horses. Each camel was shared by three men, who took turns riding. The Prophet shared his mount with Abū Lubābah and ʿAlī (may Allah be pleased with them both). When they reached a steep incline, his two companions said, “O Messenger of Allah, you ride—we will walk in your place.” But he replied, “You are not stronger than I am for walking, nor am I in less need than you are of the reward.” Thus he refused their offer and continued to take his turn on foot.

On another journey, when a sheep was to be slaughtered and cooked, the Companions divided among themselves the tasks of slaughtering, skinning, and cooking. The Prophet then said, “I will gather the firewood.” When they protested, “O Messenger of Allah, we will take care of that for you,” he replied, “I know you would not let me do it. But I dislike having any distinction over you. Indeed, Allah does not love to see a man consider himself above his companions.”

A miniature depicting a battle

(from the Siyer-i Nebî, Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, no. T. 1924, fol. 413b).

His Teachings and Commands Regarding Warfare

At Khaybar, when the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) arranged his army in ranks, he offered them counsel, instructing them not to attack until he gave permission. His words on that occasion represent one of the clearest expressions of Islam’s principles of warfare. He said:

“Do not wish to meet the enemy; rather, ask Allah the Exalted for safety! You do not know what kind of trial meeting them will bring upon you. But when you do meet them, say: ‘O Allah! You are our Lord; our foreheads and theirs are in Your hand. It is You who grants death to whom You will.’ Then sit until they come upon you, and when they advance, rise and proclaim the takbīr (Allāhu akbar)!”

The following day, the Messenger of Allah summoned ʿAlī (may Allah be pleased with him), entrusted him with the banner, and instructed him:“Proceed calmly and with dignity until you reach their strongholds. Then call them to Islām and inform them of their duties toward Allah and His Messenger. By Allah, if Allah guides even a single man through you, it is better for you than owning a whole herd of red camels.”

Although the Jewish tribes of Khaybar were already familiar with Islam and had previously been invited to the faith, the Prophet nevertheless commanded that the call be repeated. By doing so, he reaffirmed that his mission was not one of conquest or dominion but of divine guidance. At the same time, he reminded his followers—who were enduring hardship, scarcity, and hostility—that they must never lose sight of their ultimate purpose, no matter how severe the trials they faced.

On another occasion, the Prophet instructed a commander of an expedition, saying: “Deal gently with people and do not act hastily! Do not attack them until you have invited them to Islām. By Him in whose hand is the soul of Muḥammad, there is no one—whether settled or nomadic—whom it would please me more for you to bring to me as a Muslim than for you to bring me their men slain and their women (or, according to another report, their women and children) taken captive.”

This statement underscores an essential principle: just as leading a single person to guidance is more valuable than possessing red camels—the most prized wealth of the Arabs—or, in some narrations, “the whole world and all that is in it,” so too causing a person’s heart to turn away from Islām, alienating them from faith or from the community of believers, is a loss as grave as forfeiting the world and everything it contains. Therefore, a Muslim must take utmost care that their words, actions, and behavior never lead to such harm. Whether directed toward believers or non-believers, a call to faith or a word of admonition delivered without wisdom, appropriate timing, and right manner may do more harm than good.

During the Battle of Ḥunayn, when reports reached the Prophet that some of his followers had slain children among the enemy, he called out three times: “Do not kill the children!” When Usayd b. Ḥuḍayr asked, “O Messenger of Allah, are they not the children of idolaters?” the Prophet replied: “Were not your own nobles once the children of idolaters? Every child is born upon the fiṭrah (the natural disposition inclined toward faith), then when he grows old enough to express himself, his parents make him a Christian or a Jew.” When he later saw the body of a slain woman, the Prophet immediately sent word to the advance units, commanding them not to kill children, women, or servants.

His Entry into Mecca and What Followed

After the conquest of Mecca, the Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings be upon him) performed a ritual bath in his tent and requested that his camel be prepared. He donned his helmet and armor, wrapped a black turban around his blessed head, and mounted his camel, Qaṣwāʾ. Surrounded by mounted Companions, he advanced from Ḥajūn toward Ḥandamah, with Usāmah b. Zayd riding behind him. Confronted with the great victory that God had promised him from the earliest days of his mission, the Prophet was overwhelmed not with triumphal pride, but with profound humility and reverence. His head was bowed so low that the tip of his beard nearly touched the saddle of his camel, and from his lips flowed the words: “O Allah, true life is the life of the Hereafter!” ʿAbdullāh b. Mughaffal reported that he heard the Prophet repeatedly reciting Sūrat al-Fatḥ (The Victory), while Abū Saʿīd al-Khudrī related that he was saying, “This is the fulfillment of my Lord’s promise to me.” He also recited: “When the help of Allah and the victory come, and you see people entering Allah’s religion in multitudes, then glorify your Lord with His praise and seek His forgiveness; indeed, He is ever ready to accept repentance.” (Sūrat al-Naṣr, 110:1–3).

At the very moment when he attained the greatest worldly victory possible—political, military, and spiritual supremacy—the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) attached no importance to transient power or temporal glory. Instead, he turned his heart entirely toward the everlasting life and the infinite blessings of the Hereafter, thus astonishing both those who knew him and those who refused to understand him.

When he reached the Sacred Mosque (al-Masjid al-Ḥarām), the Prophet began to circumambulate the Kaʿbah while mounted on his camel. Pointing to the Black Stone (al-Ḥajar al-Aswad) with his staff, he signaled the gesture of istilām (salutation) and proclaimed the takbīr (Allāhu akbar). His Companions echoed his cry, and the sound of glorification filled the whole of Mecca. The Quraysh pagans, standing on the surrounding hills, watched in silent awe.

When the Prophet dismounted and stood before the door of the Kaʿbah, the people gathered around him. Standing elevated before them, he proclaimed:

“There is no god but Allah alone! He fulfilled His promise, gave victory to His servant, and defeated the confederates singlehandedly! O Quraysh! What do you think I shall do with you?” They replied, “You are a noble brother, the son of a noble brother. We expect nothing but goodness from you.”

The Messenger of Allah then declared: “I say to you what my brother Joseph said to his brothers: ‘There shall be no blame upon you this day. May Allah forgive you; for He is the Most Merciful of the merciful’(Yūsuf 12:92). Go, for you are all free.”

Those present were said to have risen as if from their graves, reciting the testimony of faith and embracing Islām. It is reported that among the Meccan elite—those of wealth and leadership—some accepted Islām outwardly but not yet with full conviction. The Prophet did not compel them; instead, he placed them under the status of al-muʾallafah qulūbuhum (those whose hearts are to be reconciled), granting them generous shares from the spoils after the Battle of Ḥunayn. Many of them, moved by his generosity, soon embraced faith sincerely.

When the Messenger of Allah bestowed abundant portions of the spoils upon the Quraysh and other newly reconciled tribes but gave the Anṣār little or nothing, some among them felt disheartened and murmured among themselves: “May Allah forgive the Messenger of Allah! How strange! He gives to Quraysh—(in another report: to the Emigrants and to the ṭulaqāʾ, the newly freed)—while our swords are still dripping with their blood! When hardship comes, we are summoned; but when the spoils arrive, others receive them. If this is by Allah’s command, we shall be patient; but if it is his personal judgment, then we hope he will explain it to us.” One of them even said, “Did I not tell you before that when affairs prosper, he will favor others over you?”—a remark that provoked the anger of those who heard it.

When the Prophet learned of these words, he summoned Saʿd b. ʿUbādah, the leader of the Anṣār. In one narration, Saʿd came forward and related the people’s grievances. The Prophet asked, “And what do you think, O Saʿd?” He replied, “O Messenger of Allah, I am but one of my people.” The Prophet then said, “Gather your people for me in this enclosed area (in another report: in this tent). When they have assembled, inform me.” The Anṣār gathered—all of them, without exception—while the Prophet allowed some of the Muhājirūn to attend but asked others to remain outside.

When they had assembled, the Prophet addressed them: “O assembly of the Anṣār! Did not Allah guide you when you were astray? Did He not enrich you when you were poor? Did He not unite your hearts when you were divided?” They replied, “Indeed, O Messenger of Allah! Allah and His Messenger are the most bountiful and the most gracious.” In another narration, the Prophet said, “O people of the Anṣār! Will you not answer me?” They replied, “What shall we say, O Messenger of Allah? What answer could we give? Grace and generosity belong to Allah and His Messenger.”

The Prophet then continued, with gentle reproach: “By Allah, had you said, ‘You came to us rejected, and we welcomed you; impoverished, and we enriched you; fearful, and we gave you safety; humiliated, and we supported you; denied, and we believed you,’ you would have spoken the truth—and I would have acknowledged it.”

The Anṣār once again responded, “Grace and generosity belong to Allah and His Messenger.” Then the Prophet said, “What is this that has reached me about you?” They remained silent until he repeated the question. At that point, the wise among them said, “Our elders have said nothing. Some of our young men have said, ‘May Allah forgive the Messenger of Allah! He gives to Quraysh while our swords are still wet with their blood.’” The Prophet (peace be upon him) then continued—his voice tender, his eyes filled with tears, and his heart overflowing with gratitude and affection for the Anṣār.

|

Prof. Dr. Ahmet Özel Born in 1953 in Taşlıçay (Ağrı). He graduated from the Faculty of Islamic Sciences at Atatürk University in 1977 and earned his Ph.D. from the same institution in 1982 with a dissertation titled “The Concept of Territory in Islamic Law and Its Legal Implications.” After serving in various capacities within the Presidency of Religious Affairs (1978–1985), he joined the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı (TDV) İslâm Ansiklopedisi General Directorate. Following the merger of this institution with the İSAM (Centre for Islamic Studies) in 1993, he served as a member of the Advisory Board (1996–2003), Deputy President (2005–2010), and member of the Board of Directors (2005–2022). From the inception of the TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, he contributed as an author-editor, a member of the Fiqh Editorial Board, and the Review Committee. He became associate professor in 1995 and full professor in 2012. He also taught at the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University (2011–2017), from which he later retired. His major works include: His principal works include: The Concept of Territory in Islamic Law: Dār al-Islām – Dār al-ḥarb, İz Publishing, Istanbul, 1991; Prisoners of War in Islamic International Law, Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 1995; Scholars of the Ḥanafī School, Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, first edition 1990, subsequent editions 2000 and 2022 (expanded edition: Ḥanafī Jurists and Eminent Scholars of Other Schools); Islam and Terror: A Juridical Approach, Küre Publications, Istanbul, 2005; The Hajj and ʿUmrah Handbook, Timaş Publishing, Istanbul, 2007; Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 2014; Journey to the Sacred Lands: A Guide to Hajj and ʿUmrah, Timaş Publishing, Istanbul, 2007; Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 2014; The Prophet as a Leader: Prophet Muhammad, Küre Publications, Istanbul, 2015; Imam Abū Ḥanīfa and the Ḥanafī School, Directorate of Religious Affairs Publications, Ankara, 2012; Dictionary of Religious Terms (vols. I–II), Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM) Publications, Istanbul, 2024; and In Pursuit of the Blessed Life: The New Sīra, Timaş İnanç Publications, Istanbul, 2024. |

Prof. Dr. Ahmet Özel

Born in 1953 in Taşlıçay (Ağrı). He graduated from the Faculty of Islamic Sciences at Atatürk University in 1977 and earned his Ph.D. from the same institution in 1982 with a dissertation titled “The Concept of Territory in Islamic Law and Its Legal Implications.” After serving in various capacities within the Presidency of Religious Affairs (1978–1985), he joined the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı (TDV) İslâm Ansiklopedisi General Directorate. Following the merger of this institution with the İSAM (Centre for Islamic Studies) in 1993, he served as a member of the Advisory Board (1996–2003), Deputy President (2005–2010), and member of the Board of Directors (2005–2022). From the inception of the TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, he contributed as an author-editor, a member of the Fiqh Editorial Board, and the Review Committee. He became associate professor in 1995 and full professor in 2012. He also taught at the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University (2011–2017), from which he later retired.

His major works include: His principal works include: The Concept of Territory in Islamic Law: Dār al-Islām – Dār al-ḥarb, İz Publishing, Istanbul, 1991; Prisoners of War in Islamic International Law, Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 1995; Scholars of the Ḥanafī School, Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, first edition 1990, subsequent editions 2000 and 2022 (expanded edition: Ḥanafī Jurists and Eminent Scholars of Other Schools); Islam and Terror: A Juridical Approach, Küre Publications, Istanbul, 2005; The Hajj and ʿUmrah Handbook, Timaş Publishing, Istanbul, 2007; Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 2014; Journey to the Sacred Lands: A Guide to Hajj and ʿUmrah, Timaş Publishing, Istanbul, 2007; Turkish Religious Foundation Publications, Ankara, 2014; The Prophet as a Leader: Prophet Muhammad, Küre Publications, Istanbul, 2015; Imam Abū Ḥanīfa and the Ḥanafī School, Directorate of Religious Affairs Publications, Ankara, 2012; Dictionary of Religious Terms (vols. I–II), Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM) Publications, Istanbul, 2024; and In Pursuit of the Blessed Life: The New Sīra, Timaş İnanç Publications, Istanbul, 2024.