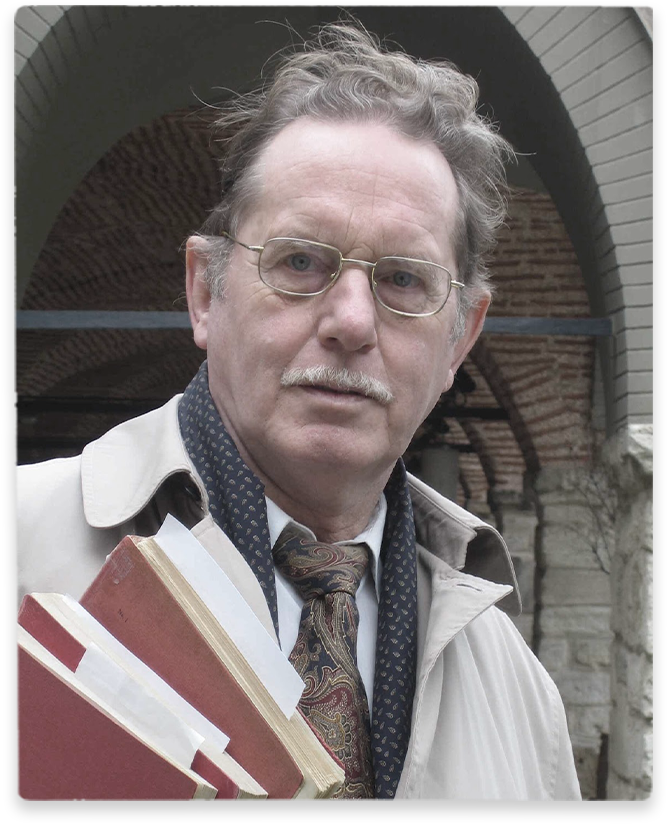

An Extraordinary Figure in Balkan Historiography: Machiel Kiel

As Recounted by Feridun M. Emecen

Arzu Güldöşüren

An Extraordinary Figure in Balkan Historiography: Machiel Kiel

As Recounted by Feridun M. Emecen

Arzu Güldöşüren

How did your collaboration with Machiel Kiel—beginning with his archival research and later continuing with the TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi—evolve into an academic relationship from your perspective?

I first met Machiel Kiel in the archives, sometime around the 1980s. I recall that during those years, while I was conducting my own research, he would frequently come there as well. He was particularly examining the tahrir registers. Later, he turned to the avârız registers and the mukâtaa registers. From time to time, he would ask me about passages he could not read, and through such exchanges we would converse. That is how we became acquainted.

Subsequently, during the work on the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi—especially after 1986—he was commissioned to prepare entries on Balkan cities. With regard to Balkan towns as well, he was asked to propose entries based on his own findings. In this way, he began to write and submit those articles from time to time.

At that period, I was working on the editing of entries on Turkish history and civilization for the encyclopedia, so I was directly involved with his submissions. During that time, he also began visiting the encyclopedia frequently. From the 1990s onward, this process became more regular. Each time he came to Istanbul, he would invariably stop by İSAM and our offices at the encyclopedia. Occasionally we would converse there, and he would show us the passages where he had difficulties, so that we might assist him as best we could.

Meanwhile, there were various congresses and symposia held both within Türkiye and abroad. I distinctly recall that we also met on such occasions. We invited him to conferences that we organized in Türkiye. And abroad, at large-scale congresses such as those of CIEPO, we participated together. At one point, he held a position at the Netherlands Institute in Istanbul, and I remember attending some of the events he organized there.

In general, our contact was not in the form of close daily collaboration, but rather through such academic endeavors and various symposia that brought us together.

In the preface you wrote for the introduction of Kiel’s work on Albania, you provided a striking summary of his approach to the Ottoman heritage and his contributions to Balkan historiography. Could you tell us about that piece?

Yes, in 1990 I wrote a review in Osmanlı Araştırmaları (published in English by IRCICA) of the book dealing with Ottoman monuments in Albania. To be honest, I had forgotten about it until now. This question brought it back to my mind, and when I looked, I saw that I had indeed written an introduction. If I read the beginning of that introduction, I believe my initial impressions regarding his scholarship, career, attitudes, and objectives will be clear. I wrote as follows:

“It is well known that the monuments of the centuries-long Ottoman domination in the Balkans have, for the past one hundred to one hundred and fifty years, been subjected to almost systematic destruction, with the aim of erasing the traces of this magnificent culture. The portrayal of the Ottoman period as one of darkness, occupation, and devastation has been perpetuated for a long time under the influence of the official ideologies of the respective countries, and this view has even prevailed in scholarly research. However, in the last thirty to forty years, studies that have concentrated on archival sources and been supplemented by local investigations have demonstrated that Ottoman administration in the Balkans needs to be re-evaluated. In this regard, at the forefront of those who, by identifying visible remains, describing them, and analyzing their artistic aspects, have sought to supplement these findings with archival sources and interpret them within a historical perspective, stands the Dutch art historian Dr. Machiel Kiel, whose research on Turkish monuments in the Balkan countries has drawn considerable attention. Alongside his numerous articles, Machiel Kiel has particularly attracted wide interest with his book on Ottoman monuments in Bulgaria. And now, he presents us with the Ottoman architectural monuments of Albania—this small country of the Balkans, long a closed book, where Islam once deeply penetrated.”

Machiel Kiel was an exceptionally valuable researcher who devoted himself to the study of Ottoman monuments in the Balkans. For him, “Ottoman heritage” did not consist solely of Islamic structures belonging to our culture—such as mosques, masjids, and zawiyas—but also included local churches that had been constructed, or more accurately repaired, during the Ottoman period. He made observations on the wall paintings and decorations of these churches, matters on which even today very few people possess any knowledge.

In Bulgaria and Greece, particularly in areas with dense Christian populations, he examined the decorations of churches in villages and small towns, and he published on them as well. In reflecting on this, he argued that these monuments should not be viewed as confined solely to Islamic works, but that churches belonging to Christians ought likewise to be considered from a shared perspective. In this way, he produced findings that invalidated the reductionist thesis claiming that “nothing was built” in the Christian regions of the Balkans during Ottoman rule. In this respect, his studies were of the utmost value.

How do you evaluate the methodological and ethical stance that Machiel Kiel adopted while working in regions marked by strong ideological pressures, such as in the case of Bulgaria?

In Bulgaria, due to his research, he was occasionally subjected to harassment. At that time, because of Bulgarian nationalism, there was severe pressure on Muslims in Bulgaria. They were being told, “You are not Turks; you are Bulgarians.” I myself once conducted research on Hazergrad in northern Bulgaria. Incidentally, Kiel also authored the encyclopedia entry on Hazergrad. In that entry, I know that he stated quite boldly that the newly founded towns and settlements had in fact been established during the Ottoman period.

In other words, he approached such matters with the stance of a neutral historian, not under any particular label or agenda. This is important to emphasize. Of course, he did not refrain from criticism; from time to time he also adopted a critical perspective toward the Ottomans themselves. But, speaking as a balanced Western scholar, he evaluated these works in a neutral manner. He was thus a significant scholar who brought an impartial perspective to bear on the subject.

Right to left: Muhammed Eroğlu, Yusuf Şevki Yavuz, Machiel Kiel, Mehmet İpşirli, Feridun M. Emecen

How did the editing and translation process of the encyclopedia entries proceed? In what way did you contribute to this process?

İngilizce yazdığı maddeleri biraz da hızlı yazdığı için zaman zaman İngilizcesi problemli olabiliyordu, anlamak zorlaşıyordu. Tabii ben mevzuyu bildiğim için hem tercümesini hem redaktörlüğünü ilk dönemlerde sıklıkla yaptım. Sonra tercüme için başka arkadaşlar devreye girdiler. Bazı bilgileri eklediğimi de hatırlıyorum çoğu maddeye. Görülemeyen yerler vardı. Veya tahrir defterine bakarak yaptıklarını kontrol ettiğimi hatırlıyorum. Redaksiyon sırasında çok iyi bir süzgeçten geçiriyorduk. Bazı yerler çıkartılarak, bazı yerler eklenerek o şekilde redaksiyon yapıyorduk. Ve sonra da bunları kendisine Türkçe olarak gönderiyorduk. O da bakıyordu bazı hatalar varsa veya başka bir şeyler varsa onları işaretleyip yolluyordu bize. Zaten tertip açısından da biz onu ansiklopedinin tertibine uyduruyorduk. Bunlar hakkında hiçbir şey söylemezdi kendisi. Genellikle bakar ufak tefek hatalar varsa veya bir şekilde yanlış bir durum varsa onları kısaca işaretlerdi. Çok önemli bir problemle karşı karşıya kalmadığımızı söyleyebilirim.

Was Machiel Kiel’s contribution to the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi limited only to the commissioned entries, or did he also enrich it with entries submitted on his own initiative?

We commissioned him to write on the principal cities and towns of the Balkans. Yet his most important contribution came through the proposals he made to us. Following his fieldwork, he would suggest highly valuable entries that even we had not identified. From the 1970s onward, he had traveled the Balkans extensively, recording everything in detail. In light of these findings, he would propose entries such as Demirhisar, insisting, “This must absolutely be written.” He would often draft and send these entries in advance.

Thus, entries would reach us without having been formally commissioned. That was his style of working, and afterwards we would approve them as encyclopedia entries before moving on to other matters. Thanks to Kiel, many small towns and settlements of the Balkans were documented in the encyclopedia. We had in fact requested this of him. I believe that, of the 127 entries he authored, the vast majority concerned these smaller Balkan towns, and they contained very valuable first-hand information. In this respect, his contribution to the encyclopedia was of great significance.

Kiel also contributed to Ottoman archival sources and methodological issues. In your view, what significance did these methodological writings hold for Balkan historiography?

He did not only focus on urban histories, but also produced methodological studies. A large portion of these have not been translated into Turkish. In some of the collected volumes he compiled, I know he sought from time to time to address such issues. Among the Ottoman tahrir registers are the cizye registers, in which he thoroughly analyzed the Christian population of the seventeenth century. In addition, there are the avârız registers belonging to this same period.

These registers take two forms in the seventeenth century. One type, which we call the mufassal avârız defterleri, resemble the sixteenth-century tahrir system and may be considered its continuation. Yet compared with the earlier tahrirregisters, they are much weaker in nature and content. This was because the tax system itself was undergoing a transformation in that period, which necessitated the compilation of these registers. Naturally, these were among the primary sources he used.

In particular, the article he wrote on the mufassal avârız defterleri became very popular. Many people still remember it. In fact, these things were already known before. They had been written about. But because his study addressed the international scholarly community, it gained a particular prominence and wide currency. In this sense, his methodological contributions may be considered especially significant.

Could you tell us about Machiel Kiel’s field trips, especially those undertaken together with his wife, Hedda?

Together with Mrs. Hedda, he traveled extensively to many places. In this way, he was able to bring together and harmonize his book-based knowledge with the geographical understanding acquired through these journeys. They traveled to Asian countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. I also know that they visited other Turkic republics as well as Iran. They would often pass through Türkiye and stop by on their way.

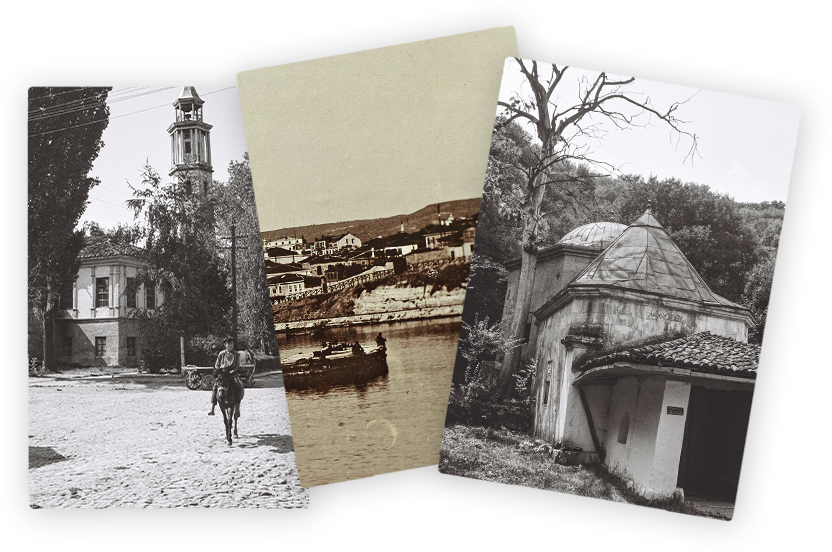

Prilep, North Macedonia, 1969 (Left)

Varna, Bulgaria (Center)

Razgrad, Kemanlar Demir Baba Tekke, Bulgaria, 1972 (Right)

Professor, what do you think was the source of his motivation for his interest in Ottoman monuments in the Balkans, as well as in the monuments of earlier civilizations?

On that matter, he himself did not say much. Yet as far as I understand, especially from the 1970s onward, his frequent travels to the Balkans must have fostered such an interest. From his biography, I also gathered this impression. He used to say that he had not undergone full formal academic training. He came from a background in masonry and stonework. Later, after receiving academic training, he entered the field. But because he came from such a practical craft background—rather than being purely academically trained—I think he possessed a sharper ability to make careful and precise diagnoses. His interest in the monuments of the Balkans arose partly in this way.

I know that he made academic efforts to promote and study these monuments, but I cannot say with certainty whether he pursued this within the framework of a particular “mission.” To me, it appears more like an academic impulse. In this sense, one could say he was sometimes ironic in his remarks, approaching things in his own distinctive way. He had a different image and background than we do, and one should not expect him to think and act exactly like us. Still, it is clear that he worked within a thoroughly academic framework. His tendency to use sources directly, without distortion, and to present them as they were, was particularly valuable.

In this respect, he made major contributions to Balkan history, especially concerning Ottoman monuments and urbanization in the region. For instance, he highlighted the fact that the Turks founded towns and introduced urban life there. His articulation of such points was often far more effective than what we ourselves might write. But he did not do this by assuming any kind of partisan mission, which I wish to emphasize.

What was Kiel’s approach to historiography? At that time, nationalist historiographies were prevalent, as you know.

It is good that you asked this question, because it allows us to clarify his stance. I know very well that he remained completely outside nationalist frameworks. His outlook was not limited merely to rejecting the harsh accusations of Bulgarian nationalism; it also reflected his academic interest in Turkish history and monuments, which he approached within the framework of scholarly concerns and his identity as an art historian—never by turning it into a kind of “mission.”

This attitude can also be seen clearly in the interviews he gave in Türkiye. For example, when asked about “the Turks in Albania,” he replied, “I am not sure.” When pressed further—“Could any have remained?”—he answered, “I do not think so.” Such responses reveal his determination to distance himself from racial or nationalist biases. These seemingly small details demonstrate that he should be regarded as a scholar—an art historian and historian—who sought to develop a neutral and methodological perspective from a Western vantage point, guided by academic concerns.

How should we assess Kiel’s contributions to academic debates in Bulgaria and Greece, as well as his impact on Balkan studies in Türkiye?

Admittedly, this is still quite recent, but I believe that through his work he served as a guide for those in Bulgaria who were able to think more academically—those who, breaking away from the classical perspective, read the registers with greater honesty. I would say the same for Greece, where, as is well known, the situation had been quite extreme. Today, in academia and in the field of history, one encounters a variety of perspectives regarding the Turks, but at that time it was much more difficult. In this sense, he was a point of reference.

In Türkiye, too, his work helped open the way for Balkan studies to some extent. There are scholars who first turned to his writings as a starting point for their own research. Especially after the 1990s, and increasingly from the 2000s onward, Turkish historiography developed a strong interest in the Balkans. Studies on cities, cultural life, and monuments multiplied, producing many books and theses. In each of these, Kiel’s influence can clearly be seen. It should also be recalled that from his earliest years, Kiel visited Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi and was influenced by him.

If you had to define Machiel Kiel in a single sentence, how would you express it?

It is difficult to capture him in a single sentence. But if I must, I would say: He was a historian who brought a fresh perspective to Balkan historiography, showing that clichés such as the “oppression of the Balkans” or the “catastrophe theory” and “dark age” narratives concerning the Turks were not entirely accurate. In this sense, he offered scholars a more inclusive and scholarly methodology, thereby enriching the field.

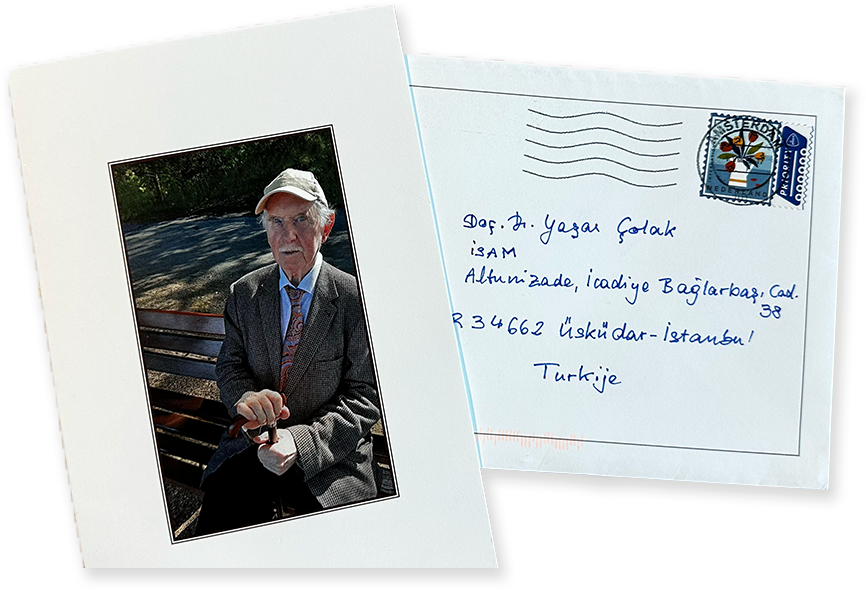

The funeral/memorial service invitation for the late Machiel Kiel, conveyed to our institution by Hedda Reindl-Kiel

Prof. Dr. Feridun Emecen

He completed his doctoral degree in Ottoman history at Istanbul University in 1985. He was appointed associate professor in 1989 and full professor in 1995. Prof. Emecen has held various administrative positions at Istanbul University and is currently serving as the Dean of the Faculty of Letters at Istanbul 29 Mayıs University. With numerous works and studies in various fields of Ottoman history, Prof. Emecen is recognized as one of the leading experts particularly on the classical period of the Ottoman Empire and its preceding era. His honorary membership in the Turkish Historical Society and membership in the Turkish Academy of Sciences attest to his distinguished position in historical scholarship. In 2014, he was awarded the Turkish Culture Research Prize by the Elginkan Foundation. Among his published books are Fetih ve Kıyamet 1453 (The Conquest and the Apocalypse 1453), Yavuz Sultan Selim, Osmanlı’nın İzinde (In the Footsteps of the Ottomans), İlk Osmanlılar ve Batı Anadolu Beylikler Dünyası (The First Ottomans and the World of the Western Anatolian Beyliks), Osmanlı Klasik Çağında Hanedan, Devlet ve Toplum (Dynasty, State, and Society in the Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire), Osmanlı Klasik Çağında Savaş (War in the Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire), and Osmanlı Klasik Çağında Siyaset (Politics in the Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire).

|

Arzu Güldöşüren He graduated from the Faculty of Letters at Istanbul University (2000). He completed his master’s degree at the Institute of Social Sciences, Marmara University, with his thesis titled “Ilmiye Ricali According to Tarik Registers in the First Half of the 19th Century” (2004) and earned his Ph.D. with his dissertation “The Ottoman Ulama in the Era of Mahmud II” (2013). He served at the Foundation for Science and Arts (2015–2018). In 2024, he was awarded the title of Associate Professor. He is currently affiliated with the TDV Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM). |