Ramazan Yazıları III

Farewell, O Month of Fasting

Welcome O Day of Eid

İskender Pala

Ramazan Yazıları III

Farewell, O Month of Fasting

Welcome O Day of Eid

İskender Pala

Divan poets have frequently been subjected to negative criticism regarding their perceived failure to reflect their temporal reality in poetry. Particularly in the period following the establishment of the Republic, certain official ideologies labeled this literary tradition as detached from real life and, over the years, adopted an approach aimed at erasing Divan poetry from our cultural memory, primarily through its exclusion from school textbooks. However, careful examination of Divan literary products readily reveals the injustice of these judgments. Indeed, all contemporary research in Divan literature emphasizes facts that contradict this dismissive attitude. We now propose to examine certain scenes of traditional life through the lens of Ramadan, Eid al-Fitr, and festive celebrations, drawing not from general ramazāniyyes or īdiyyeles but specifically from the verses of a single poet: the 16th-century Janissary poet Üsküdarlı Aşkī (d. 984/1576).

Aşkī’s divan contains three īdiyyes (festival odes), one of which was composed for Eid al-Fitr, as evidenced by the couplet:

Rûzede irdi kemâle kâr-ı takvâ vü salâh

Câm-i cem sun sâkîyâ zevk ü safâdır şân-ı ıyd

Here the poet declares: “O cupbearer! Piety and sincere devotion reached perfection through fasting. Now offer the cup of Jamshid, for the glory of Eid lies in joy and merriment.” The poet suggests he has attained spiritual excellence during Ramadan through ascetic practice, yet his unruly soul cannot maintain this state – with Eid’s arrival, it yearns for revelry. He justifies this by pronouncing “The essence of Eid is celebration” – a remarkable statement considering this was the era of Süleyman the Magnificent when alcohol prohibitions were most stringent.

Let us examine our own contemporary experience: After the Three Sacred Months and their blessed nights, the Ramadan fast, and Laylat al-Qadr, we greet Eid as if having earned paradise, slipping into complacency (or so we imagine). More troubling, with Eid’s commencement we swiftly abandon the spiritual refinement and devotional intensity cultivated during Ramadan, reverting to our baser selves. Sins avoided during the holy month suddenly seem permissible again. Taverns fill with those who have “completed their annual worship” (!), while Islamic injunctions recede before more frivolous behaviors. This transformation manifests across all spheres – from television programming to newspaper columns, commercial establishments to government offices. Eid is indeed for celebration – but what manner of celebration? From this perspective, Aşkī’s couplet appears strikingly relevant to modern conditions.

Aşkī, renowned for his murabbas, expresses heartfelt emotions about Ramadan’s conclusion in this tekerrürlü murabba:

On bir aylık râhdan gelmişdin ey mâh-ı sand

Eylemişti pertevin halkın günâhın nâbedîd

İsmetinle ağzına iblîsin urmuşdun kilid

Hak müyesser ede ferhunde hilâlin bir dahi

Kim bile kime nasîb ola visâlin bir dahi

Görevüz ayn-ı riyâzetle cemâlin bir dahi

Elvedâ ey mâh-ı rûze merhabâ ey rûz-ı ıyd

Her menâr üzre kanâdilden geçirdin tavk-ı nûr

İ’tikâf ashâbının kalbine bahş ettin sürûr

Sür’at ile kıldın âhir ömrümüz gibi ubûr

Elvedâ ey mâh-ı rûze merhabâ ey rûz-ı ıyd

In the first stanza, the poet portrays Ramadan as a blessed sovereign arriving after an eleven-month journey, its radiance effacing people’s sins and locking Satan’s jaws – the latter image being authenticated by hadith. This demonstrates the remarkable consistency in Islamic perspectives on Ramadan across centuries. In the second stanza, the poet begins by mentioning the Ramadan crescent. Even today—despite colossal telescopes and the advanced developments of astronomical science—the sighting of the Ramadan crescent remains one of the enduring religious controversies in the Islamic world. Debates such as “Was it seen? Was it not? Someone saw it; someone else didn’t…” recur every year, much like a refrain repeated without end. Evidently, in Aşkî’s time, this issue was not nearly as contentious, for he speaks in the verse with notable certainty.

He then declares, “Who knows to whom the reunion will be granted once again?” On the final day of Ramadan, do we not all still utter some variation of this line—whether aloud or silently to ourselves? It is essentially a Ramadan-centered articulation of the age-old phrase, “Who shall live, who shall die?” On the first day of Eid, when all stand equal regardless of whether they fasted, people often express such thoughts—not only as a reckoning of the soul, but also as a reflection of the serenity, spiritual clarity, and gentle refinement that a month of fasting brings.

These words seem to echo a kind of wistfulness, as if to say:

“If only we could remain in the same state as we were during Ramadan! Yet, beginning with the very morning of Eid, we embark upon a long and testing journey—a period requiring patience, inner vigilance, and constant struggle with the self. God willing, we may once again reach the next Ramadan to seek forgiveness for the faults we will inevitably commit during these eleven intervening months.”

In the final stanza of the murabba we have chosen, Aşkî describes enduring Ramadan traditions: the adornment of minarets with lanterns, the custom of mahya (illuminated inscriptions between minarets), and the i‘tikaf (spiritual retreat) observed during the last ten days of the holy month. These are scenes of Ramadan that remain very much alive even today. The poet then invokes a familiar expression to reflect the fleeting nature of time:

“You passed by swiftly, like life itself.”

Indeed, Ramadan often feels as though it slips away in an instant. This perception is no doubt shaped by the way the month is filled with activity, reflection, and spiritual engagement.

The refrain of the murabba, echoing with the cadence of a hymn or the glow of a mahya inscription, encapsulates this transition with striking beauty:

Elvedâ ey mâh-ı rûze, merhabâ ey rûz-ı ıyd

Farewell, O month of fasting; welcome, O day of festivity!

Or, in the contemporary idiom of today’s mahya banners:

Aşkī composed two ghazals intertwining Ramadan and Eid themes. One particularly noteworthy ghazal includes these couplets:

Keşf olup yine nikâb-ı rûzeden dîdâr-ı ıyd

Kalbine mü’mînlerin verdi safâ envâr-ı ıyd

Eid’s countenance unveiled from behind Ramadan’s veil

Filling believers’ hearts with joyful radiance

Rûze-i hicrinde ıyd-ı vaslının müştâkına

Arz edip cânâ hilâl ebrûnu kıl izhâr-ı ıyd

O beloved, display your crescent brows to those fasting in separation’s anguish

That they might rejoice as at Eid’s arrival

Rûzedârân-ı firâk olanlar eylerler niyâz

Nâz ile salınan her bir serv-i gül ruhsâr-ı ıyd

Those keeping separation’s fast continually pray

For the swaying, rose-cheeked cypress-tall beauties of Eid

Yok demez virür metâ-ı vasla cânın müşterî

Her kaçan gün yüzlülerle germ ola bâzâr-ı ıyd

No buyer says ‘no’ but gives his soul for union’s merchandise

When sun-faced beauties animate the Eid market

Allar gülgûnîler geymiş çü her bir lâle-had

Taze güllerle donanmış ser-be-ser gülzâr-ı ıyd

Each tulip-cheeked beauty wears crimson and rose

The Eid garden blossoms with fresh roses.

Kılsa vaslında gönül bûsen temennâ etme ayb

Dûstum âdettir eyler cerrini cerrâr-ı ıyd

If my heart craves kisses in union, don’t reproach

For even beggars ply their trade at Eid, dear friend

Ömr-i âdem gibi kûtehdir zamân-ı vasl-ı yâr

Aşkîyâ anı güzer kılmakda olmuş yâr-ı ıyd

Like human life, beloved’s union is brief

Eid itself helps speed its passing, Aşkī

The moment of union with the beloved is as fleeting as human life. O Aşkī! Even Eid itself becomes an accomplice in hastening its passing.

This ghazal preserves several Ramadan and Eid-related cultural motifs that remain vibrant to this day:

The opening couplet captures the growing festive anticipation among fasting believers as Eid approaches. The second couplet depicts the traditional race to sight the Eid crescent – a practice still observed with fervor. The third couplet references the enduring belief in the special efficacy of prayers made at iftar, particularly the lover’s supreme supplication: the rose-cheeked beloved’s graceful arrival at breaking fast.

Subsequent verses transport us to the Eid bazaar. Then as now, pre-festival markets thrum with exceptional vitality and abundance. The poet’s quest to “purchase” his beloved in this setting suggests 16th century marketplaces differed little from their modern counterparts in their festive commercial energy.

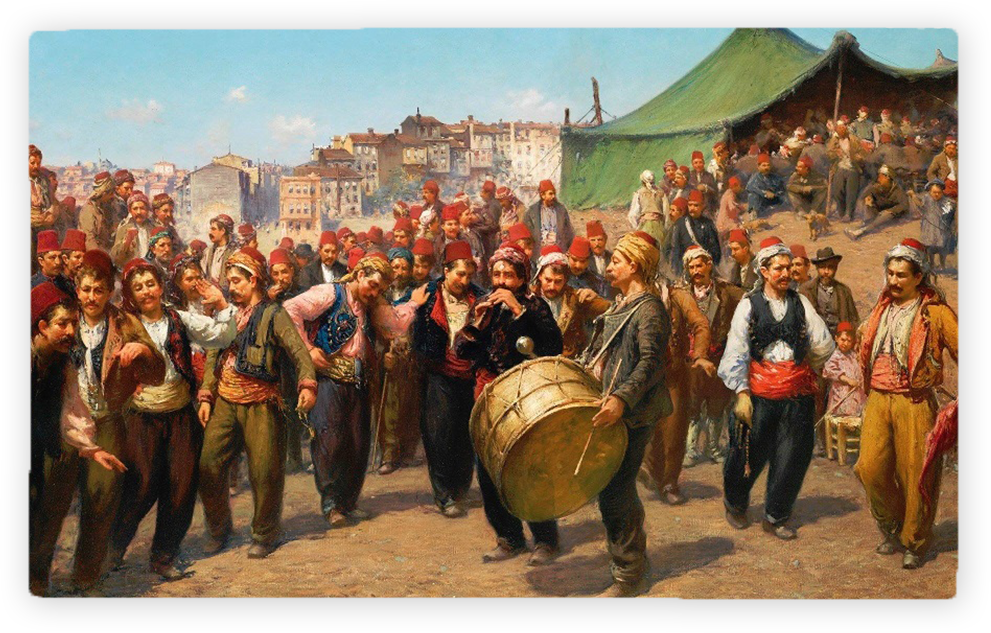

The fifth couplet paints a vivid panorama of traditional Eid festivities. While Aşkī’s era knew no amusement parks, its festival grounds certainly featured swings, sweet vendors, acrobats and illusionists. Traveling menageries might display exotic beasts – perhaps some lethargic lion from distant Cathay, roaring halfheartedly (!). Fortune-tellers, candle-makers, prayer bead craftsmen and fez vendors would have completed the scene. But the true essence of these celebrations lay in their crowds of tulip-cheeked beauties in crimson and rose – much as provincial festival grounds today still swarm with mustachioed youths pursuing rosy-cheeked maidens.

The sixth couplet documents the “cerr” tradition: During the Three Sacred Months, madrasa students would disperse to rural mosques to preach, receiving sustenance from villagers – a dignified form of seasonal begging. By later centuries this custom degenerated, with neighborhood toughs replacing the scholar-beggars of old. In my own childhood, I witnessed remnants of this practice: On Arefe day after dawn prayers, groups would go door-to-door chanting rhymes (“oil money! salt money! grape stems! pear stalks!”) to collect treats – a tradition surviving today in the ceremonial Ramadan drummers’ manis. The closing couplet returns to the motif of Ramadan’s swift passage.

Yet this very literature, often dismissed as elitist and detached from the people, has in fact articulated the essence of the populace itself—their faith, their seasons of joy and sorrow, their daily rituals, the bustling excitement of festivals, and even the inner struggle against the self (nafs), all in an exquisite manner. The poet has witnessed the glow of Ramadan lamps (mahya) and heard the silence of the retreating dervish in spiritual seclusion (i’tikaf); they have captured in verse both the delight of a child passing by the sweet-seller at the festival grounds and the reckless fervor of the self dashing toward the tavern. In short, all that exists in life exists in poetry; all that resides in the people resides in the Divan. Were it not for the verses of a poet like Aşkî, we today could never imagine what was lived or felt in the aftermath of a 16th-century festival. For Divan poetry is not merely an aesthetic art of words—it is also the memory of our culture, the history of our civilization written in verse

Clearly, there are cultural and folkloric values that have endured unchanged since the 16th century, and it was Divan poetry—the same poetry we long accused of being alien to the people—that documented them. How many modern poets, I wonder, now turn their gaze so intently upon the people and their values, invoking them in their verse? Or let us ask instead: How many of the “common folk” (kara budun) today consider contemporary poets their own, or feel any connection to them?

“Divan poetry is detached from the people?” Don’t make us laugh.

|

İskender Pala Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.” With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak. His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages. Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies. |

İskender Pala

Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.”

With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak.

His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages.

Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies.