Interview with Mehmet İpşirli

“A European Friend”

Arzu Güldöşüren

Interview with Mehmet İpşirli on

“A European Friend”

Arzu Güldöşüren

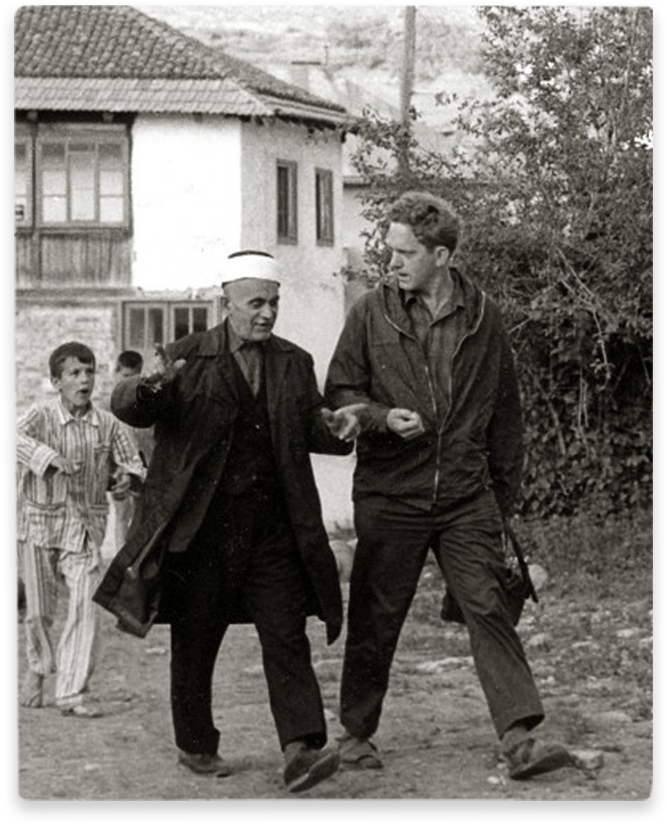

Machiel Kiel with the village imam in Pljevlja (Taşlıca), Montenegro, 1967

How did you learn about the passing of Machiel Kiel, who is renowned for his significant and original contributions to Balkan history?

When I heard the news yesterday morning, I was truly saddened. His final days had been rather difficult. I learned from his wife—who is also a distinguished colleague—Hedda Kiel, that due to illness he had been residing in a nursing home. I had sent her a photograph of us together, to which she replied, “Professor İpşirli no longer recognizes those around him. But perhaps, upon seeing this picture, he may suddenly recognize.” Naturally, we were deeply grieved by his passing. May God, if He wills, have granted him guidance. In our tradition, when referring to non-Muslims, documents often include the phrase—expressed in the form of a prayer—that you also know: Hutimet avâkibuhu bi’l-hayr. That is, “May God bring his end to goodness, and transform it into good.” I wish to emphasize this especially for our colleague Machiel Kiel.

When and under what circumstances did your first contact with Machiel Kiel take place?

Our acquaintance began in the 1970s at the Prime Ministry Archives. He would often ask his colleagues questions about documents he was unable to read, and thus we had occasional conversations. However, our genuine familiarity and closer relationship developed through İSAM, via the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. At that time, we were considering, “To whom shall we entrust the entries on Balkan cities?” We were primarily assigning Professor Semavi Eyice to write on architectural works in Türkiye. Since we were also acquainted with Machiel Kiel, we thought, “Let us commission him with one or two trial articles and see how he writes.” We did not know exactly how he would approach the task.

The entries he produced pleased us greatly. If I recall correctly, he began with the entry on Athens under the letter A. Afterwards, more followed. This was particularly significant for us, since the Ottoman Empire is widely recognized as a Balkan state, indeed as a European state. Europeans themselves emphasize this point even more frequently than we do. It was therefore essential that our historical presence in the region be presented appropriately—without advertisement or propaganda. And the fact that Ottoman monuments there were described by a foreign scholar lent the work an additional layer of value. A Muslim or a Turk, of course, might risk exaggeration, and such issues naturally arise.

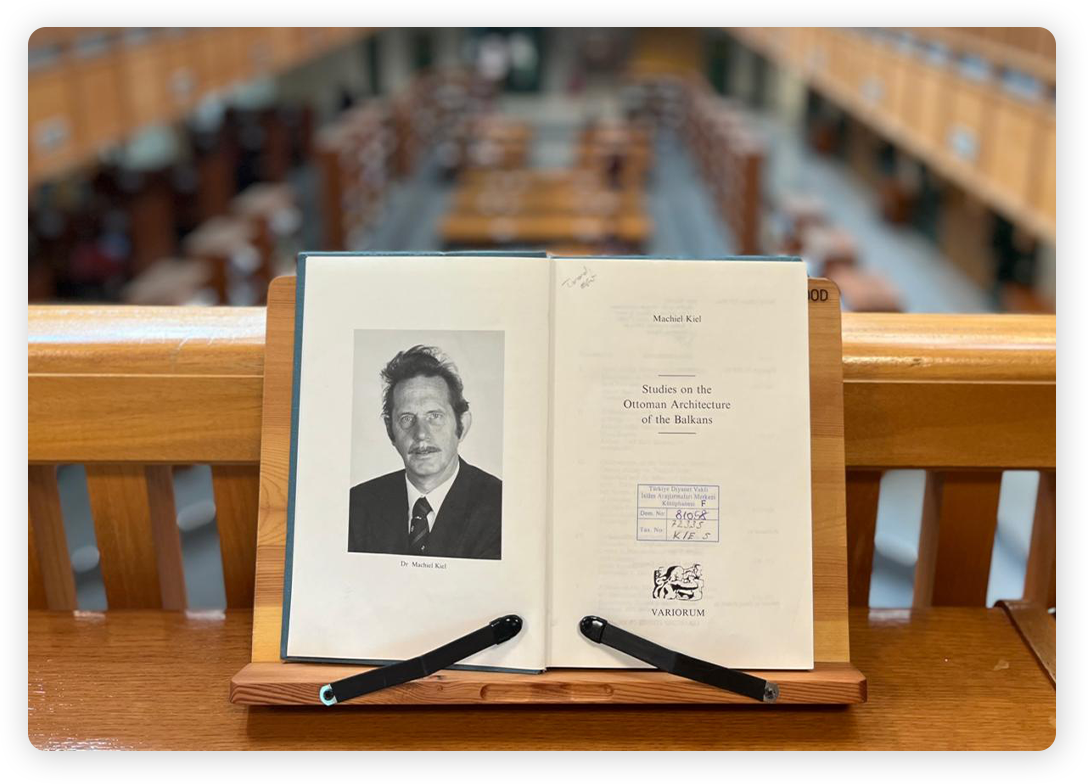

In the end, we commissioned him with over one hundred entries. With each new article, he opened up further, drawing attention to important aspects. Kiel spoke Turkish fluently, but his academic language was English. He was originally Dutch. He had begun these pursuits as an amateur, working on the restoration of various monuments. Later—if I am not mistaken, sometime in the 1980s—he completed his doctorate.

How do you evaluate the historical development of interest in Ottoman architecture in the Balkans within Türkiye’s academic and intellectual circles? In this context, how would you position Kiel’s work?

Ottoman architecture in the Balkans represents one of our greatest treasures. Although independent states have now been established there, and we recognize the independence of each, that region remains our geography of the heart, our geography of culture. We never forget it. Two essential elements stand out there: one is the architectural heritage, the other is the presence of our people. Some are Turks, some are Muslims—Albanian Muslims, Macedonian Muslims, Romanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Pomaks, and others. These two resources are of immense importance to us—not only for the past but, more importantly, for the future. That is why we were so pleased that Machiel Kiel dedicated himself wholeheartedly to this subject.

It should be emphasized, however, that this interest did not begin with Machiel Kiel. Before him, the late Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi—who was truly a monumental figure—conducted extensive field research in the Balkans during the 1970s, with the support of the Ministry of Culture and a large team. They photographed all the monuments they encountered, spoke with local people, and upon returning, did not stop there. They delved into the archives, researching the documents of the very same monuments. In addition, they made use of works by Evliya Çelebi, Kâtib Çelebi, as well as various Western travelers. As a result, Ayverdi produced five monumental volumes under the title Avrupa’da Osmanlı Mimari Eserleri(Ottoman Architectural Monuments in Europe).

In the introduction to his work, he even mentions the late Machiel Kiel. If I remember correctly, this occurred in the 1960s, though I am not entirely sure. He writes something to the effect of: “A young Dutchman came. He was very curious, eager, and asked us many questions, trying to gather information. But I could not follow what became of him afterward.” Thus, Kiel had an early beginning with regard to the study of Ottoman monuments in Europe.

When writing his articles, Machiel Kiel knew those places intimately, step by step. He constantly traveled through the region. In fact, he came to be regarded as an undesirable figure in both Greece and Bulgaria. The reason, as he himself recounted, was accusations such as: “Whose man are you? You are working in favor of the Turks. You are always trying to bring these things to the forefront.” He stated that, from time to time, he faced harassment and pressure for this very reason.

Could you provide information on the types of sources Kiel consulted in his studies on Ottoman architecture, and the manner in which he used them?

He possessed a rich array of sources, employing both our own and foreign materials—though he relied primarily on ours. What were these? Chief among them were the tahrir registers, as they contained precisely the type of information he sought. For the seventeenth century, he made extensive use of the avârız registers, and subsequently of the mühimmeregisters, which he employed in a highly effective manner.

Speaking of the mühimme registers, I should like to recount an anecdote. One day he came to the encyclopedia offices, around midday. He said, “İpşirli, could you take me to the Nurbanu Sultan Mosque?” The mosque is close to the encyclopedia, located in Atik Valide. I asked, “What is the matter?” He replied, “I will explain on the way.” So, we got into the car and went—it was quite close. As we arrived, the call to prayer began. He said, “You perform your prayer; I will sit quietly at the back and watch in peace.” He sat at the rear portico. After I finished the prayer and the congregation dispersed, he said:

“Let me tell you why I came. In the rear portico, there are some eight or ten marble columns. Two of these columns were later additions, meaning they do not belong to the time of Nurbanu Sultan.”

When I asked, “How do you know?” he replied:

“In the mühimme register there is a decree regarding this matter. It states that two marble columns, each two to two and a half meters long, were brought here from elsewhere. I need to see for myself what their quality and structure are.”

What he later wrote on that matter, I do not know. Afterwards, we returned again to the encyclopedia.

At the encyclopedia, he was held in very high esteem. A foreigner had embraced our culture—and he wrote beautifully as well. On one occasion, he came again to the encyclopedia and said: “İpşirli, could you arrange for me to meet with an authority here? I have a very important matter concerning a monument in Bulgaria.” Tayyar Bey, the founder of the institution and our most senior figure, was the appropriate person. I took him to Tayyar Bey, and Kiel explained:

“Professor”—he spoke Turkish; it was only in his writings that he used English—“in Bulgaria, the first mosque commissioned by Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror…” (at this point, he immediately pulled out a photograph from his pocket and showed it) “…is on the verge of destruction. The Bulgarians are deliberately destroying these monuments in order to erase them. Could anything possibly be done? I am already considered an undesirable person there, but even at the risk of being beaten, I would go and remain on site to ensure it is preserved.”

Tayyar Bey became very animated by this. Later, at a dinner, he said to me: “İpşirli, just look at our situation—consider the concern shown by this foreign man of seven layers’ distance!” He was deeply moved by Kiel’s dedication.

We were speaking about the sources he used, so let me return to that point. He made very effective use of Evliya Çelebi. He employed the vekāyi‘nâmes only sparingly—I do not know why, though in truth they do not contain much relevant information. So it is not that he never consulted them, but rather that his use was limited. Beyond that, he also utilized Kâtib Çelebi’s Cihannümâ. To illustrate more recent circumstances, he drew upon salnâmes. Another was Şemseddin Sâmi’s Kāmûsü’l-a‘lâm. These were among his principal sources, and he made effective use of them. And of course, he also employed European sources.

Another noteworthy point is that his second wife, Hedda, was also a historian. She specialized in prosopography during the reign of Bayezid II, focusing particularly on Gedik Ahmed Pasha and his circle. It was the first study of its kind in our context. Since his wife was also a historian, they often came together. The gathering place was Kemal Beydilli’s office, known as the Dergâh. Professor Feridun [Emecen] and Kemal Beydilli worked there side by side, and everyone would gather in that space—Machiel Kiel among them, of course.

Allow me to recount another memory of him. One day I asked, “Would you deliver a lecture at the university on the Ottoman heritage in the Balkans?” He replied, “Gladly.” So we invited him. He said: “I can lecture in Turkish with no problem, but I will explain myself more comfortably in English, as all of my writings are in English.” He began his talk, and at one point he said: “There are many Ottoman monuments in the Balkans. The attitudes of the Balkan peoples toward this heritage can be divided into two groups.” He was speaking in English: “The first group, they were very respectful, very elegant, very sensitive,” and he went on to list five or six such adjectives. “The second group—öküz(oxen),” he said. Yes, indeed. The audience of students and faculty members was very large, and the hall erupted in laughter.

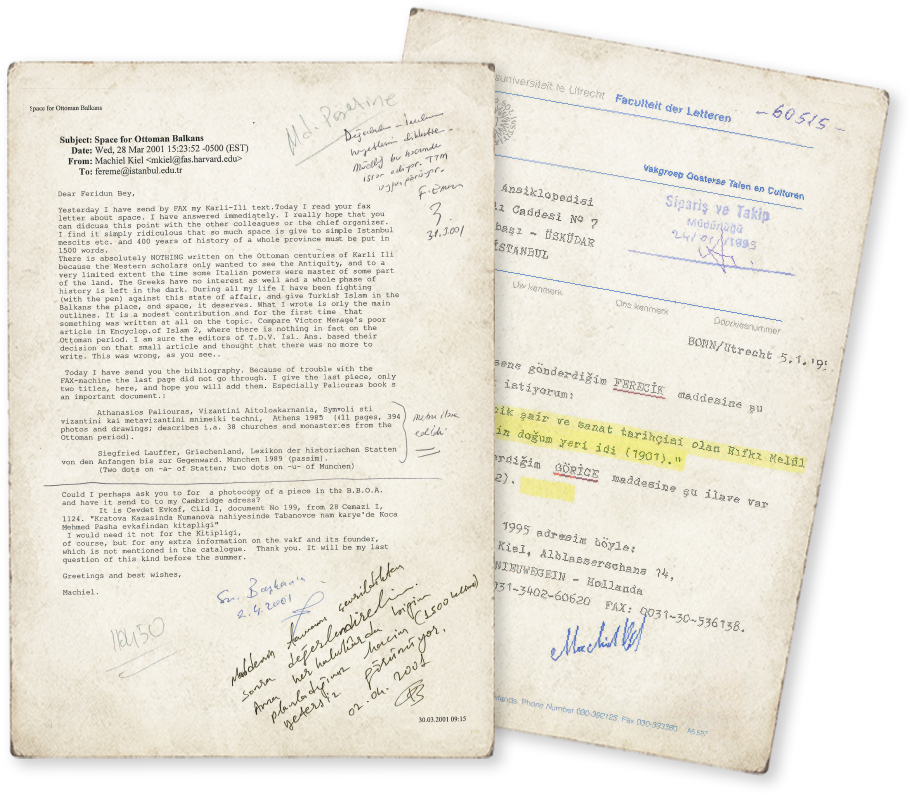

Correspondence between Machiel Kiel and the DİA Order Tracking Unit during the article-writing process

In what ways do the entries that Machiel Kiel wrote on Turkish history and civilization for the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi differ from other encyclopedia entries?

Like Evliya Çelebi, Machiel Kiel had a sort of template—how to begin, how to proceed. I do not think there was an excessive amount of evaluative commentary; rather, his work was primarily descriptive in nature. His entries were concise, succinct, and conveyed only what needed to be said. They never included unnecessary detail. What we most appreciated was that he wrote with objectivity. To my knowledge, he was a Protestant. Yet his ability to write in an objective manner was deeply reassuring for us. This was precisely in line with the mission of the encyclopedia.

In terms of depth—of course, I am not an art historian, and were you to ask one, they might offer a different perspective—but from our standpoint, he provided accurate information. And such information became part of the scholarly record. Some of those monuments may no longer exist today—they are being destroyed daily.

In what ways have the entries that Machiel Kiel wrote for the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi functioned as a reference source in historical education and field research?

I regard these entries as a highly significant contribution. From the letter A to the letter Z, we commissioned him without hesitation. He wrote in simple English, and the texts were then translated within the encyclopedia. As far as I know, almost all of them passed through the hands of Professor Feridun Emecen, just as virtually all the history entries did. If you pay attention to the photographs he used—mosques, madrasas, and so on—you will see that they were all taken in the Balkans. At first they were in black and white, later they became color images.

I also recommend Kiel’s articles to my students. The fact that they were written by a foreign scholar makes them all the more appreciated. From time to time, we organized field trips to the Balkans with our students. Before setting off, we would photocopy the relevant encyclopedia entries. When traveling to Thessaloniki, for instance, I would assign one student the task: “Read Thessaloniki,” and the student would read the encyclopedia entry aloud. Or when entering Athens, the entry on Athens would be read. Once the students arrived, they would then conduct research on these topics. I am certain that these entries have been read and used by thousands. Of course, the value of Kiel’s entries should also be asked of architects.

Varna, Bulgaria

What do you think about the difficulties and negative experiences he encountered while researching the Ottoman heritage in the Balkans?

He said that he had been harassed, even roughed up on occasion. But this was not something unique to him. Professor Halil İnalcık also experienced similar difficulties. He once recounted: “I was studying the foundation period of the Ottoman Empire. I went to the Gelibolu region. There a soldier came and said, ‘What are you doing here? I will take you to my commander.’ We went to his commander, who likewise questioned me: ‘We have seen many a hodja; tell me, what is your true purpose here?’ One of my students—he was teaching at the Military Academy, I believe—scolded that commander so harshly: ‘What are you doing? How dare you speak this way!’ After that, their attitude changed.” I suspect Machiel Kiel experienced similar situations.

What sort of innovation and pioneering role did his in-depth field research on Ottoman architecture in the Balkans represent for the academic world?

He served as a visiting scholar in various places. In Europe, there are those who are professors—that is, who lecture at universities—and then there are institute members. If you ask an institute researcher to teach a course, he trembles, for he has never taught in his life. Yet he may be a first-class researcher. Such was Machiel Kiel. He certainly gave lectures and conferences, but his true focus was research. He was not one to say, “Let me examine this as well, and that too.” His central concern was the Ottoman monuments of the Balkans. Day and night, he was occupied with them, and since he did not scatter his attention, he naturally achieved greater success.

How did Kiel obtain the financial means necessary to continue his fieldwork in the Balkans, and how did he manage this process?

Of course, the encyclopedia provided him with an author’s fee, and he attached great importance to it. Machiel Kiel was not someone who lived in luxury. He would say, “That money is very important to me. I will use it to travel to such-and-such a place.” He was always calculating and budgeting—he stated this openly, without hesitation. It was not a large sum, and we were often astonished by how much it mattered to him. Sometimes we even arranged for his payments to be made early. He would come and ask, “Could I collect the fee for this?” even before it had been processed. We would have Mr. Sabahattin handle the paperwork.

None of us working in these fields lived in comfort, but all labored with great enthusiasm. Machiel Kiel was one of them. He wore the same clothes for years, yet he would say, “I went to such a place today. Tomorrow I will go to such-and-such a museum.” He had an incredible zeal.

What impact did Kiel’s long-term field and archival research have on international academic circles?

Professor Ekmeleddin [İhsanoğlu] was among those who truly appreciated his worth. Two of his works were published by IRCICA. One concerned Bulgaria: Art and Society of Bulgaria in the Turkish Period. The other was on the monuments of Albania: Ottoman Architecture in Albania: 1385–1912. I do not think anyone else could have presented these subjects as masterfully as he did. These were not projects of three or five months’ effort. If I am not mistaken, he first went to Bulgaria in the 1960s, when he was in his twenties. From then on, he established a heartfelt bond with the region and continued to travel back and forth. Imagine: a journey that began in 1960 and continued into the 2010s, 2015s, perhaps even the 2020s.

How do you view İSAM’s project to publish Kiel’s encyclopedia entries as a book? In your opinion, what kind of contribution would such a publication make to academic and cultural memory regarding the Ottoman heritage?

The project to publish the entries he wrote for the encyclopedia is an excellent one. It will be released as a book in both English and Turkish. Its publication by İSAM will be a significant gain for our cultural history.

What are your impressions of Kiel’s personality? What kind of character did he have?

As a person, he was somewhat like a reserved European. He would smile when spoken to, but he was not the type to tell jokes, anecdotes, or to be cheerful and lively. His mind was always preoccupied. Yet he was a good listener.

If you were to describe Machiel Kiel in a single sentence, how would you express it?

He was, in the truest sense, a European friend, a colleague, and a valuable scholar who served our culture and art with objectivity and impartiality. As my final remark regarding him, I would say: “May God, if He wills, have granted him guidance.” I would wish to conclude with the phrase always used in Ottoman documents when referring to Westerners: Hutimet avâkibuhu bi’l-hayr—“May God bring his end to a good conclusion.”

Vidin Fortress, Bulgaria, 1969 (Left)

Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina (Right)

Prof. Dr. Mehmet İpşirli

Born in 1945 in Kayseri, he graduated from the Istanbul Higher Islamic Institute in 1967 and from the Faculty of Letters at Istanbul University in 1970. He completed his M.A. (1971) and Ph.D. (1976) at the University of Edinburgh. He began his academic career as a research assistant in the department from which he had graduated. In 1982, he was appointed associate professor with his dissertation The Institution of the Chief Military Judge (Kadıaskerlik) in the Ottoman Empire, and in 1988, he became full professor with his study The Mahzar from a Diplomatic Perspective. He served as the founding chair of the Department of Archival Studies at Istanbul University (1987–1999). Between 1983 and 2016, he worked as an author and editor for the Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi (Encyclopaedia of Islam). In 2018, he was awarded the Presidential Grand Prize for Culture and Arts in the field of History and Social Sciences. He is currently a faculty member in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Istanbul Medipol University.

His major works include Tarih-i Selânikî (Istanbul, 1989, 2 vols.); Tarih-i Naima (Ankara, 2014, 6 vols.); and Osmanlı İlmiyesi (Istanbul, 2021).

|

Arzu Güldöşüren He graduated from the Faculty of Letters at Istanbul University (2000). He completed his master’s degree at the Institute of Social Sciences, Marmara University, with his thesis titled “Ilmiye Ricali According to Tarik Registers in the First Half of the 19th Century” (2004) and earned his Ph.D. with his dissertation “The Ottoman Ulama in the Era of Mahmud II” (2013). He served at the Foundation for Science and Arts (2015–2018). In 2024, he was awarded the title of Associate Professor. He is currently affiliated with the TDV Centre for Islamic Studies (İSAM). |