“Kneel Before Emîrî Efendi”

Notes on Book Fairs and Bibliophiles

Beşir Ayvazoğlu

“Kneel Before Emîrî Efendi”

Notes on Book Fairs and Bibliophiles

Beşir Ayvazoğlu

Although some publishers claim that the time they devote to book fairs costs them the production of several books, they still make a point of attending at least one fair each year. These events offer a unique opportunity to showcase their publications collectively and to take the pulse of their readers through face-to-face interaction. At the fairgrounds, everyone strives to present what they have in the most striking and eye-catching manner possible. In this regard, book fairs have gradually come to resemble a kind of ritual for publishers, authors, and readers alike. Taking place in a festive atmosphere, these fairs bring writers and readers together at book signing events and are further animated by panels, open forums, and conferences. Their contribution is, without doubt, undeniable. At the very least, they ensure that—if only briefly—books and the structural problems of the publishing industry manage to find a place, however modest, on the media agenda. Many people, having learned of book fairs through newspapers, radio, or television, find themselves drawn by curiosity to visit them on a weekend. Immersing themselves in the crowd, they often encounter—for the very first time—the scent of books. Indeed, it is often through these fairs that people experience their first meaningful contact with the book as a tangible, authentic object. Serious readers, on the other hand, are given the chance to meet the authors they admire, to speak with them face-to-face, and to obtain signed copies of their works. But…

When it comes to the reality behind this glittering facade: A foreigner unfamiliar with Turkey’s conditions might assume, based on the enthusiasm at events like the TÜYAP Book Fair, that our people are avid readers. However, with few exceptions, print runs range between one and two thousand copies, and most books never go beyond their first edition. Many publishers express satisfaction not because they sell a lot of books at fairs, but because they manage to convert at least some of their stock into cash. Everyone knows that more than three-quarters of fair visitors are merely spectators…

Years ago, I classified the visitors to book fairs as follows: authors who come to give talks, participate in signing events, or check if their books are selling; genuine bibliophiles who spend the entire week at the fairground to see thousands of books in one place and inhale the intense scent of printed paper; those who understand the importance of reading but are too busy to do so, and who assuage their guilt by attending a few fairs each year and buying a handful of books; penniless intellectual aspirants who sit in the café during the fair, breathing in the smell of cellulose; lively students who come on their teachers’ recommendation; those who only collect catalogs; ordinary citizens who drop by out of curiosity, marvel at the thousands of books, and wonder, “Who will read all these?”; those influenced by the media who buy piles of books for show but never open a single cover all year; those who wander aimlessly; and even thieves…

One of the important functions of book fairs is undoubtedly bringing authors together with their readers. I find this encounter beneficial and necessary; however, for some authors, signing events can be a kind of nightmare—they feel exposed and uncomfortable, as if on display. Others avoid signing events out of fear of sitting idly with no one approaching them. Indeed, sitting with a pen in hand, waiting for someone to ask for an autograph, can be deeply humiliating and distressing. I have even witnessed some readers treating authors as shopkeepers, asking for books by authors they know from social media. Recently, at book fairs, while long queues form in front of stands where young authors with no presence on social media sign books—queues that even surprise other popular authors—the stands of very significant authors fall into a pitiful silence after signing a few books for acquaintances. In short, book fairs have turned into showgrounds for media-savvy popular authors and social media influencers.

If you ask me, for true bibliophiles, fairs are merely spectacles. They can always find the books they seek, no matter the circumstances. They are more interested in rare books; they frequent bookstores and second-hand shops rather than fairs, buying books not because they are trendy or widely discussed in the media, but because they need them like air or water. They are so passionate about books that they might kiss and smell a book when they find it. They have particular sensitivities; for example, they never read lying down, despise amateur bookbinders, and are driven to fury by those who dog-ear pages or wet their fingers to turn them. They never leave books open, stack them open on top of each other, dry flowers between their pages, bind different books together, or remove any illustrations, maps, or photographs. There are many who never marry because of their love for books or who divorce their wives out of jealousy for their books. They take pride in their libraries, built through detective-like pursuits, and look down on those who inherit ready-made libraries. For them, the thrill lies in the chase and the eventual acquisition of a coveted book. Once, when someone mentioned Rıza Pasha’s library to Ali Emîrî Efendi (1857-1924), he retorted, “Rıza Pasha’s library? Which library? That’s Ahmet Vefik Pasha’s (d. 1891) library. Rıza Pasha didn’t collect it; he found it ready-made!”

Needless to say, such libraries are fiercely guarded by their owners and envied by their rivals. İbnülemin Mahmud Kemal never allowed anyone into his library, and those he permitted to see it were never left alone. Mithat Cemal Kuntay (1885–1956) would sometimes dream that books he couldn’t afford were gifted to him by friends. One anecdote that perfectly encapsulates bibliophilia is this: The famous orientalist Sir Thomas W. Arnold (1864–1930), upon hearing Helmuth Ritter (1892–1971) mention an autograph manuscript of al-Bīrūnī’s (d. 1061?) Taḥdīd al-Nihāyāt al-Amākin during a chance encounter in Bebek, rushed to the Süleymaniye Library. The library director at the time swore that when Sir Thomas held the book, he kissed the colophon page.

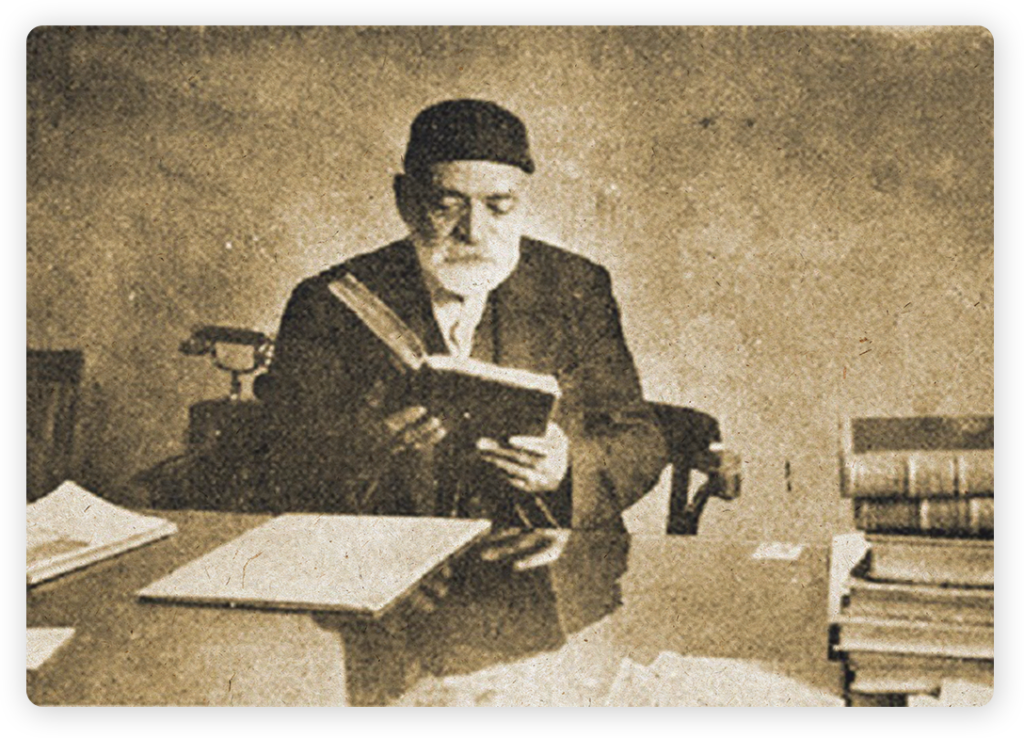

Some bibliophiles have very specific interests. Rıza Pasha, whom Ali Emîrî Efendi disparaged, was one such collector; his library contained three or four manuscript copies of the same book—one for its illumination, another for its calligraphy, and yet another for its binding. These kinds of bibliophiles can instantly recognize a valuable and important book and will go to great lengths and make significant financial sacrifices to acquire it. Mithat Cemal Kuntay, in his article “Book Lovers” published in the June 1937 issue of Her Ay magazine, masterfully portrays Emîrî Efendi, a lifelong bachelor who devoted his entire income to collecting rare books. The discovery of the Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, a work of immense importance for our linguistic and cultural history, and its subsequent acquisition by Sadrazam Talat Pasha in a staged performance, is a tale so thrilling it could be the subject of a novel. Kilisli Rifat Bilge (1874–1953) recounted this adventure in six articles published in the Yeni Sabah newspaper in 1945.

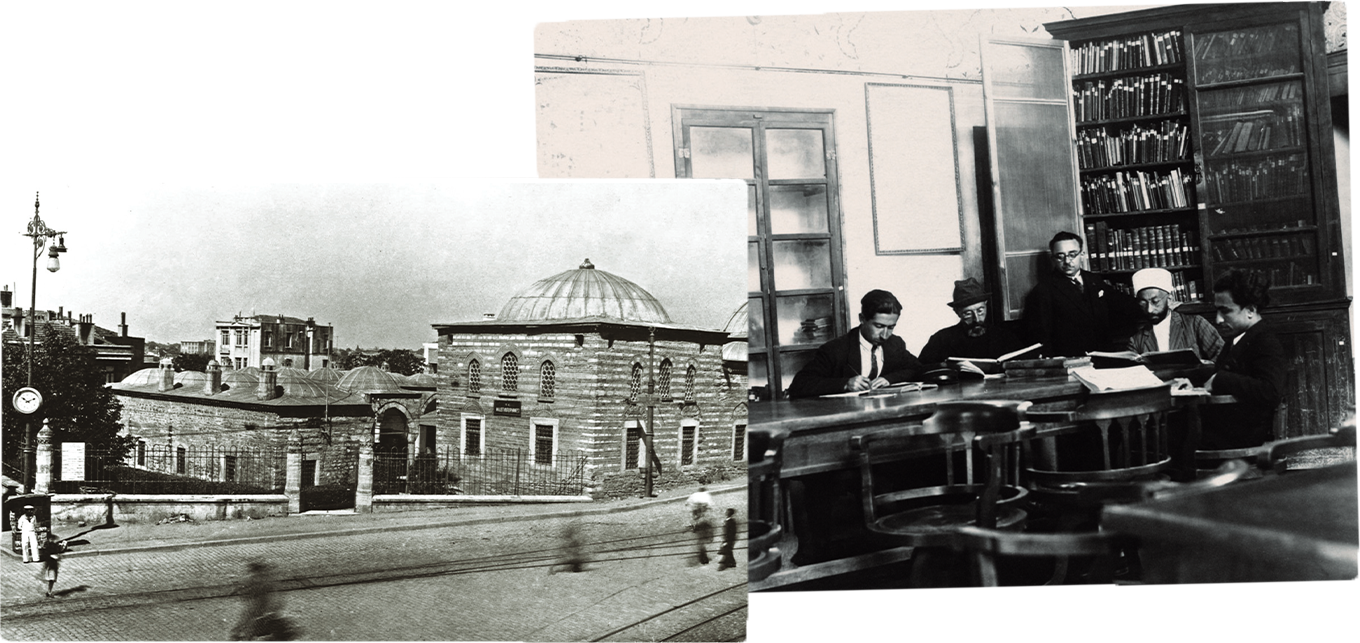

The Millet Library, founded by Ali Emîrî, to which he donated his books – Millet Library reading hall.

The love of books can sometimes turn into an uncontrollable passion and extreme jealousy. As I once read in an article by Mithat Cemal: According to Saint-Simon, a count named Astre, who was illiterate, amassed a collection of 52,500 books, while a bibliomaniac named Don Vensant shot a friend after failing to acquire a coveted book at an auction. There are even rare book enthusiasts who rejoice at the death of those who own books they desire, or who steal from libraries. Recently, the market for rare books has been inflated by wealthy collectors, making many books inaccessible. True bibliophiles are those who do not hoard their collections but use them and allow others to benefit from them as well. Emîrî Efendi was a jealous bibliophile, but he ultimately bequeathed his library to the nation, earning him a magnificent elegy by Yahya Kemal (1884–1958):

Muhtâc isen füyûzuna eslâf pendinin

Diz çök önünde şimdi Emîrî Efendi’nin

Âmid o şehr-i nûr öğünsün ilelebed

Fazl u fazîletiyle bu necl-i bülendinin

If you seek the wisdom of the ancients,

Kneel now before Emîrî Efendi.

Let the city of light boast forever,

Of the virtue and excellence of this noble soul.

I would like to conclude this article by sharing a passage from a lengthy interview I conducted with the late Nuri Aralasez, who, like Ali Emîrî Efendi, never married and spent his life abstaining from worldly pleasures to collect manuscripts, eventually donating his treasure-like collection to the Süleymaniye Library without expecting anything in return:

“The late Raif Yelkenci was a gentleman of refined character, one of the brightest representatives of Ottoman customs and traditions. Many years ago, I had the fortune of visiting his small shop once again. He handed me a rare Kelâm-ı Kadim (a manuscript Qur’an) and said, ‘Please, pay your respects!’ In my hands was a small, exquisite Kelâm-ı Kadim, likely written in 16th-century Iran, of exceptional beauty and rarity. In a moment of profound calm, he said, ‘I want you to have this Kelâm-ı Kadim.’

After expressing that my financial means were very limited, I added, ‘I gazed at this Kelâm-ı Kadim with my entire being, as if my eyes had become one with it. As a result of this gaze, this blessed Qur’an will materialize in my mind’s eye every time I close my eyes, as if I could touch it. Therefore, by the grace of God, this Kelâm-ı Kadim will be mine whenever I desire it.’ Raif Efendi, with the insight of those who are ‘the salt of the earth,’ as the Bible puts it, said, ‘I have no doubt that this Kelâm-ı Kadim will be yours every time you close your eyes, but I still want you to have it. There is a strange necessity here!’

It turned out that an Arab emir wanted to acquire this exquisite manuscript Qur’an and was willing to pay any price. But the late Raif Bey said, ‘The emir has plenty of money, yes, but he lacks the passion as we understand it. You have no money, but you have the passion. Therefore, this Kelâm-ı Kadim is drawn to you.’ But how would I pay for it? ‘Please don’t make this a big issue. Take this blessed book and disappear as soon as possible. We’ll settle the matter between us later,’ he said. Approximately a month later, when I returned to discuss the matter, he said, ‘Whenever you have some extra money, you can give what you can. You don’t even need to know how much you’ll give!’

That’s what true Istanbulites, true Ottomans, were like, my son. Those people are gone, and so is that Istanbul!”

|

Beşir Ayvazoğlu Beşir Ayvazoğlu was born on February 11, 1953, in the Zara district of Sivas, Turkey. He completed his primary and secondary education in Sivas and pursued his higher education in Bursa. Starting from 1976, he worked as a literature teacher in various high schools, as an expert at the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), and as a writer and editor at several newspapers and magazines. He also served as a consultant at the Ministry of Culture for a period. Between November 2001 and July 2005, he was a member of the Radio and Television Supreme Council. From 2005 to 2015, he managed the journal Türk Edebiyatı (Turkish Literature). Beşir Ayvazoğlu has published around sixty books and has been awarded numerous prizes in various fields. His other books published by Alfa Publishing Group include: My Life Was a Flame: The Life, Art, Aesthetics, and Drama of Ahmet Haşim (2006), The Great Agha: Tarık Buğra (2006), The Dream of Conquest in the Ruins (2006), The Anthology Book (2006), 1924: The Long Story of a Photograph (2006), Forty Portraits in My Notebook (2007), The Secret of the Ney (2007), Florinalı Nazım (2007), Peyami: His Life, Art, Philosophy, and Drama (2008), Biographies and Portraits (2008), Yahya Kemal: The Man Who Returned Home (2008), From the Mountain of God to Mount Hira (2009), The Lost Poem (2009), The Divan Road (2010), Malik Aksel: The Painter of Our Home (2011), How Would You Like Your Coffee? (2011), Dersaadet at Night (2013), The Sea of Fire (2013), The Aesthetics of Love (2013), Yunus, How Beautifully You Have Spoken (2014), He’s Two Eyes, Two Fountains (2014), Clocks, Souls, and Cats(2015), Literature’s Trial with Çanakkale (2015), A Spark, A Thousand Fires (2017), The Golden Gate (2018), Haşim (2019), Fikret (2019), A Yusuf in Every Well (2021), The Other Souls (2022), Ataç: Prospero Against Caliban (2023), The Dreams of Lady Çiçek (2024), Kemal: The National Poet’s Trial with the Republic (2024). |

Beşir Ayvazoğlu

Beşir Ayvazoğlu was born on February 11, 1953, in the Zara district of Sivas, Turkey. He completed his primary and secondary education in Sivas and pursued his higher education in Bursa. Starting from 1976, he worked as a literature teacher in various high schools, as an expert at the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), and as a writer and editor at several newspapers and magazines. He also served as a consultant at the Ministry of Culture for a period. Between November 2001 and July 2005, he was a member of the Radio and Television Supreme Council. From 2005 to 2015, he managed the journal Türk Edebiyatı (Turkish Literature). Beşir Ayvazoğlu has published around sixty books and has been awarded numerous prizes in various fields. His other books published by Alfa Publishing Group include:

My Life Was a Flame: The Life, Art, Aesthetics, and Drama of Ahmet Haşim (2006), The Great Agha: Tarık Buğra (2006), The Dream of Conquest in the Ruins (2006), The Anthology Book (2006), 1924: The Long Story of a Photograph (2006), Forty Portraits in My Notebook (2007), The Secret of the Ney (2007), Florinalı Nazım (2007), Peyami: His Life, Art, Philosophy, and Drama (2008), Biographies and Portraits (2008), Yahya Kemal: The Man Who Returned Home (2008), From the Mountain of God to Mount Hira (2009), The Lost Poem (2009), The Divan Road (2010), Malik Aksel: The Painter of Our Home (2011), How Would You Like Your Coffee? (2011), Dersaadet at Night (2013), The Sea of Fire (2013), The Aesthetics of Love (2013), Yunus, How Beautifully You Have Spoken (2014), He’s Two Eyes, Two Fountains (2014), Clocks, Souls, and Cats(2015), Literature’s Trial with Çanakkale (2015), A Spark, A Thousand Fires (2017), The Golden Gate (2018), Haşim (2019), Fikret (2019), A Yusuf in Every Well (2021), The Other Souls (2022), Ataç: Prospero Against Caliban (2023), The Dreams of Lady Çiçek (2024), Kemal: The National Poet’s Trial with the Republic (2024).