Ramadan Writings II

The Journey Of Loyalty To Hejaz:

The Tradition Of Surre

İskender Pala

Ramadan Writings II

The Journey Of Loyalty To Hejaz:

The Tradition Of Surre

İskender Pala

Surre, in its most common sense, refers to a purse filled with money, that is, a money pouch. During the Ottoman period, the wealthy would invite the poor, scholars, and students of night madrasas to iftar (the evening meal to break the fast), and after the meal, they would give them small pouches filled with coins. The common folk called this “diş kirası” (tooth rent), while the religious scholars referred to it as “surre.”

From this perspective, the tradition of surre can be seen as an institution of mutual aid, a method of assisting the poor and needy. The 19th-century poet Fâzıl mentions surre in one of his couplets:

Bilmem ki nice bu ramazân ü nice bu ıyı

Ne sâat ü ne şâl ne ihrâm u ne surre

We saw neither a watch, nor a shawl, nor an ihram, nor a surre (a pouch of gold).

I cannot comprehend what kind of Ramadan or what sort of Eid this was!

In this couplet, the poet laments that by the 19th century, the tradition of surre had begun to fade, and no one was giving “diş kirası” or surre during iftar. Today, this tradition has completely vanished. Iftars have multiplied, but not for the purpose of giving surre—rather, for collecting money during iftar! Be that as it may…

The term “surre” gained its true significance in our history through the “surre procession” (surre-i hümâyun). Surre-i hümâyun refers to the money and gifts sent by Ottoman sultans to Mecca and Medina. The name derives from the fact that the cash gifts were placed in small pouches.

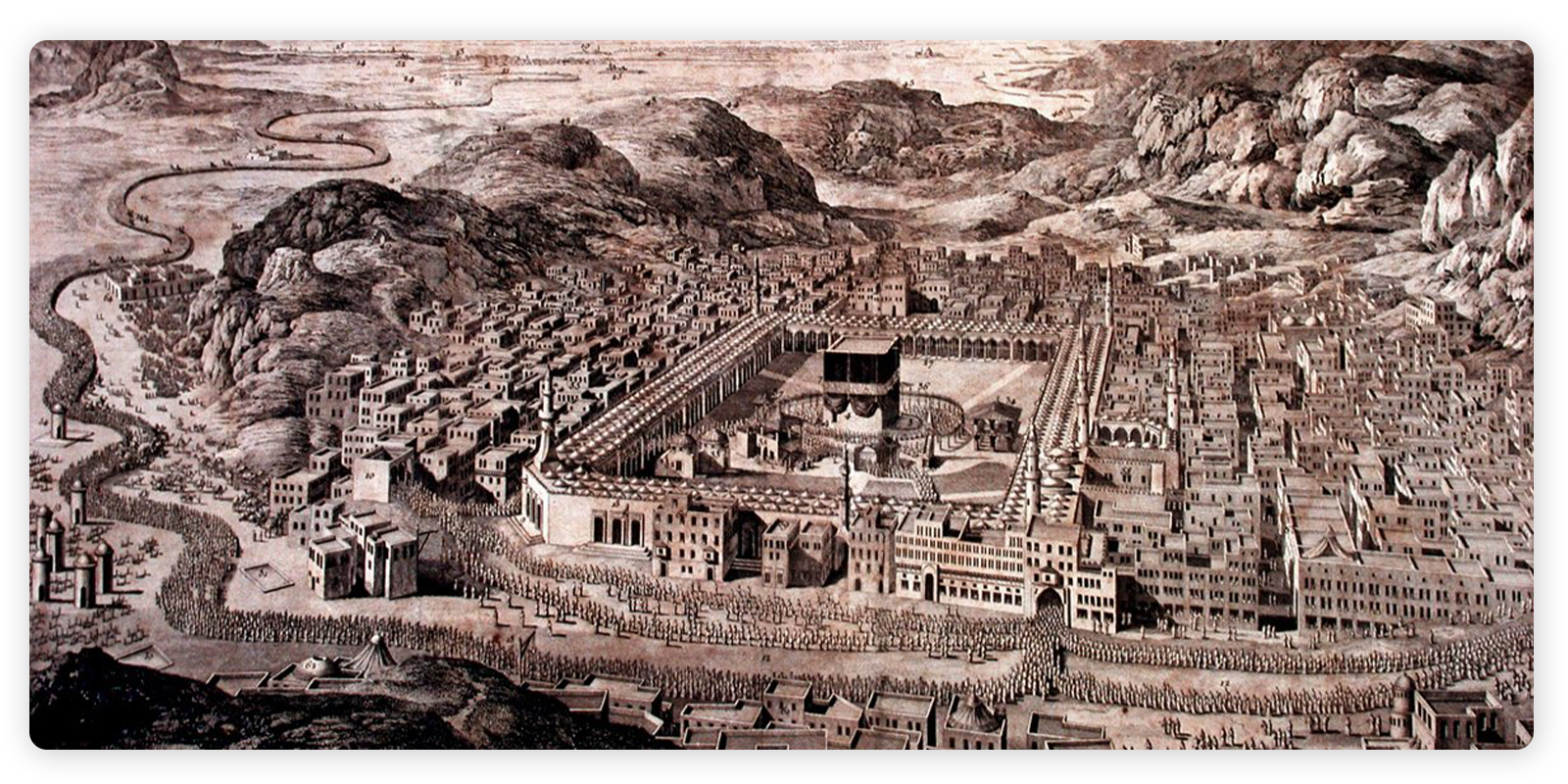

Every year, on the 12th of Rajab, a caravan would depart from Topkapı Palace, led by a surre emini (surre official), and travel for months until it reached the Haramayn (the Two Holy Mosques).

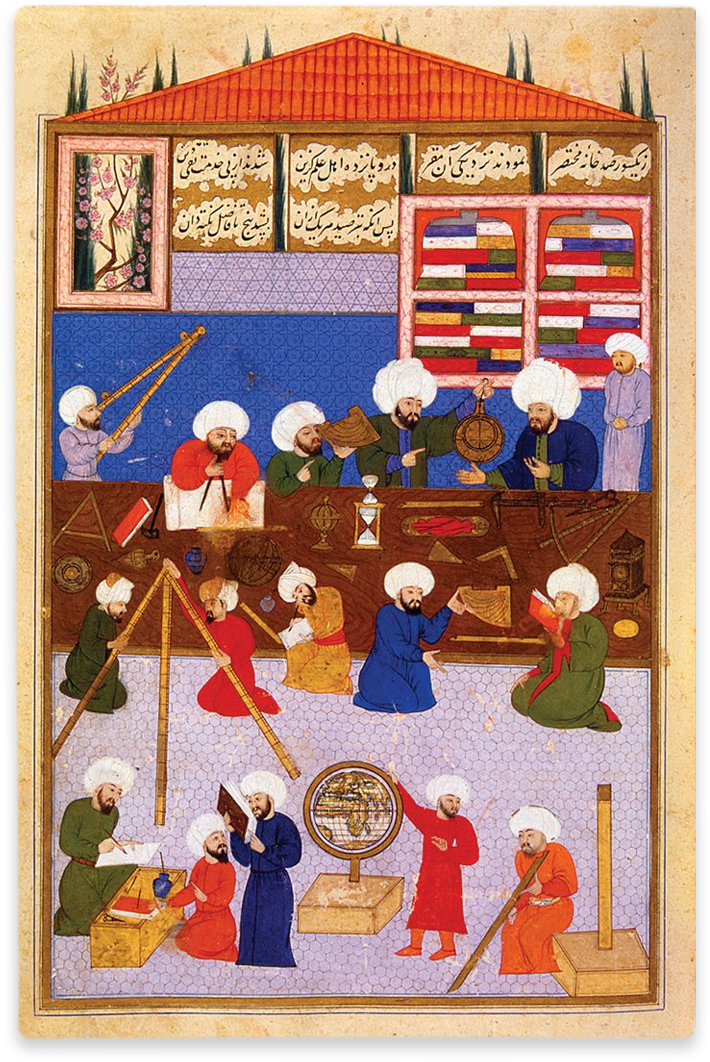

The first surre procession in history was organized by the Abbasid caliph Al-Muqtadir Billah (923-924). Among the Ottoman sultans, the tradition of surre began with Çelebi Mehmet (1413-1421). These charitable surres took on an official and political significance after Yavuz Sultan Selim secured the sacred relics and the caliphate for the Ottomans. The income, which the people of Hijaz awaited with the phrase “Sadâkat-i Rûmiyye” (Loyalty of the Anatolians), was of vital importance to the bedouin Arabs, who had no oil or Hajj tourism. The surre allocation, which increased gradually each year, reached 3,514,000 kurush during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II. This tradition continued until the British incited Arab tribes to revolt against the Ottomans. Even in 1918, when the Ottomans could barely find funds for the war, they did not neglect to send a surre procession worth 3,650,000 kurush.

After the opening of the Suez Canal, the departure date of the surre, which previously traveled by land and was sent on the 12th of Rajab, was changed to the 14th of Sha’ban.

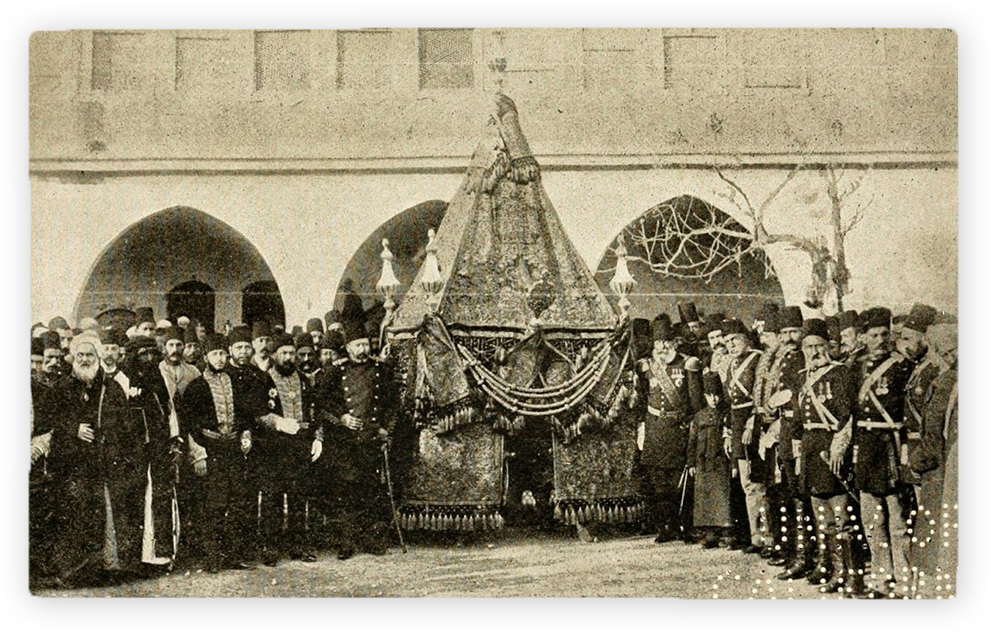

In the Ottoman capital, the departure of the surre procession carried a festive atmosphere. The Ottoman sultans, who saw themselves as the “Servants of the Two Holy Mosques” (hâdimü’l-Haremeyn), did not reject the contributions of the people and included them in the surre procession. Thus, cash and gifts

collected over days at Topkapı Palace were loaded onto mules, and the sultan’s gold was carried by the chief of the palace eunuchs, who led the camels by their reins in front of the divan for all to see. Afterward, the surre procession was handed over to the surre emini, an elderly and highly trusted official chosen for that year. Verses from the Quran were recited, and naats (poems in praise of the Prophet) were sung as the procession set out toward Beşiktaş. Along the way from Topkapı to Beşiktaş, the caravan grew as mules and gifts allocated by the people were added, and the roads became scenes of festive celebrations as crowds gathered to watch. The camels destined for Hijaz were adorned with carpets and silks, their necks and legs decorated with ornaments and henna. At the head of the procession rode 12 mounted officers, followed by foot soldiers, then the chief doorkeeper, and finally the surre emini and the surre steward, along with the splendid surre caravan. Around the camel carrying the sultan’s surre marched about 30 soldiers, followed by mules laden with money and goods to be distributed to the poor of Mecca and Medina, and finally the crowd of onlookers. The procession, resembling a parade, would reach Beşiktaş and then cross by sea to Üsküdar. After spending the night in Üsküdar, the surre procession would set out again the next day amid festive crowds, heading toward the Haramayn. Prayers were recited, filling hearts with light and joy.

The surre processions, which were met with great respect and affection wherever they passed, undertook journeys lasting months. This noble tradition, which delivered sacred relics to the holy lands and was maintained with unwavering devotion for centuries, adorned a glorious chapter of Ottoman history and the hearts of thousands. Many old engravings still capture the magnificence of this tradition.

THE CRESCENT APPEARS

In recent years, an issue of great concern to the Islamic world has emerged: The sighting of the Ramadan and Eid crescent.

The sighting of the Ramadan and Eid crescent has perhaps never been as contentious as it has been in recent years, with people falling into such confusion. One might even jest, “The telescope was invented, and fasting was ruined!”

Be that as it may!

Our main concern here is to speak of the crescent as seen by the ancients.

The Hijri lunar months begin with the sighting of the crescent moon; when the crescent of Shawwal is sighted, the month of Ramadan is completed, and the time of Eid is reached. Divan poets frequently mentioned both Eid and the crescent, using this occasion to express their feelings for their beloveds in classical forms. One such poet, the 16th-century Janissary poet Aşkî, says:

Sen hilâl-ebrûdan ayru ıyd mâtemdir bana

Kimse bayrâm eylemez çün kim görünmeye hilâl

O beloved, without your crescent-shaped brow, Eid is but mourning for me,

For no one celebrates Eid if the crescent does not appear.

Here, the poet compares his beloved’s brows to the crescent, suggesting that seeing her crescent-like brows brings him joy, while an Eid without her is akin to mourning. Indeed, for those separated from their loved ones, Eid is a source of sorrow. Only those who have experienced the pain of being apart from their loved ones during the festive days of Eid can truly understand this. May Allah grant patience and victory to those who are far from their homes or whose homelands are engulfed in war and strife!

One who spends the days of Ramadan fasting longs for Eid. This longing is akin to a lover’s yearning for their beloved. Poets often liken fasting to separation and sorrow, while Eid represents reunion and joy. Consider this couplet by Ahmet Pasha, the vizier of Fatih:

Çektim firâkın savmını erdim cemâlin iydine

Aç leblerin meyhânesin ney gibi nâlân et beni

I endured the fast of separation and finally reached the Eid of your beauty. (Now, O beloved!)

Open the tavern of your lips and make me lament like a reed flute.

The poet associates Eid with fasting, suggesting that fasting is a prerequisite for celebrating Eid. In the second line, he pleads for sweet words from his beloved’s lips, which would intoxicate him like wine. Thus, a kind word from the beloved is like Eid, the sighting of the crescent.

During Ramadan, the tradition of “hân-ı yağma” (plunder feast) iftars is well-known. Nâilî, referencing this tradition, highlights the Eid crescent as follows:

Rûzedârı hân-ı yağmâ-yı visâle Nail

Gurre-i mâh-ı muharremdir hilâl-i câm-ı ıyd

O Nâilî! For the fasting ones gathered around the plunder feast of union with the beloved,

the crescent of the Eid cup is like the first days of Muharram.

The poet suggests that those who attain union with their beloved are reborn, beginning a new life like the start of a new year.

Aşkî İlyas Efendi, playing with words, beautifully describes fasting and Eid:

Öldürdü idi kâfir-i nefsimizi siyah

Olmasa idi dahi penâhı hisâr-ı ıyd

Had we not sought refuge in the fortress of Eid,

fasting would have nearly killed our sinful selves.

While the poet rejoices at the arrival of Eid for the sake of his soul, his words imply that a few more days of fasting might have completely subdued his ego. Thirty days were not enough for the blessed fast!

|

İskender Pala Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.” With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak. His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages. Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies. |

İskender Pala

Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.”

With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak.

His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages.

Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies.