The Missing Link in Archaeology:

Muslims, Cultural Heritage and Colonialism

Bilal Toprak

The Missing Link in Archaeology:

Muslims, Cultural Heritage and Colonialism

Bilal Toprak

One of the pivotal turning points in human history was undoubtedly the multifaceted transformations of the 19th century. During this period, marked by the acceleration of the Industrial Revolution and colonial expansion, the objects of exploitation were not limited to land and people; hegemony was also deeply felt in domains such as science, thought, and art. This aforementioned mindset, which perceives itself as the center of power, civilization, science, and thought, has either treated non-Western cultures as historical objects to be exhibited in museums or has acknowledged them only to the extent that they serve its own interests. Within this framework, even though the roots of science extended far into antiquity, it was increasingly asserted during this period that science was fundamentally a post-Enlightenment Western phenomenon. Yet the West, despite having benefited significantly from the scientific and philosophical heritage of ancient civilizations—particularly those of Mesopotamia, India, China, and the Islamic world—largely ignored these contributions. Instead, it promoted a narrow narrative that traced the origins of science almost exclusively to Greek and Roman sources.

The 19th century, in which the foundations and diversification of the social sciences in their Western sense became more clearly established, was also a period deeply shaped by colonialism. Within the logic of Eurocentrism, the functions of various disciplines were aligned with the objectives of imperial domination. While some branches of the social sciences were designed to address the problems of Western societies, others were tailored to study non-Western societies—those already colonized or perceived as possessing colonial potential. In this context, disciplines such as sociology focused on Western social structures, while economics addressed Western markets. Meanwhile, fields like anthropology and Orientalism were developed to explain the pre-Western stages of humanity and to define and extract resources from non-Western societies.

In this regard, particularly within the Anglo-American tradition, archaeology was subsumed under anthropology and evolved in close association with colonialism from its very inception. Considering the high costs associated with archaeological excavations, it is hardly surprising that the discipline’s development and sustainability were heavily dependent on imperial powers.

A review of the literature on the history of archaeological thought frequently presents archaeology as a modern science emerging in the 19th century. According to this narrative, earlier societies were allegedly indifferent to material culture and did not regard it as a source of knowledge. But is this depiction accurate? Did people before the Enlightenment truly fail to recognize material remains as meaningful sources of historical understanding? Were they indifferent to the ruins they encountered? The conventional history of archaeology suggests that civilizations outside the Greco-Roman sphere—indeed, outside the Western world—did not engage with material culture in a significant way. It asserts that our knowledge of Egypt and Mesopotamia derives mainly from Greco-Roman accounts and biblical references. Within this framework, even the Roman peasants’ interpretation of prehistoric artifacts—such as stone axes and spearheads—as supernatural objects is deemed noteworthy. By contrast, societies in the Near East are often portrayed as having shown insufficient interest in archaeological remains, which, according to the modern narrative, explains why the scripts, arts, and architectural legacies of ancient regional civilizations remained undeciphered and unstudied in a systematic manner until the 19th century. In other words, it is claimed that Muslims and other groups, who ruled the region for over a millennium, made no substantial contributions to the study or preservation of material culture.

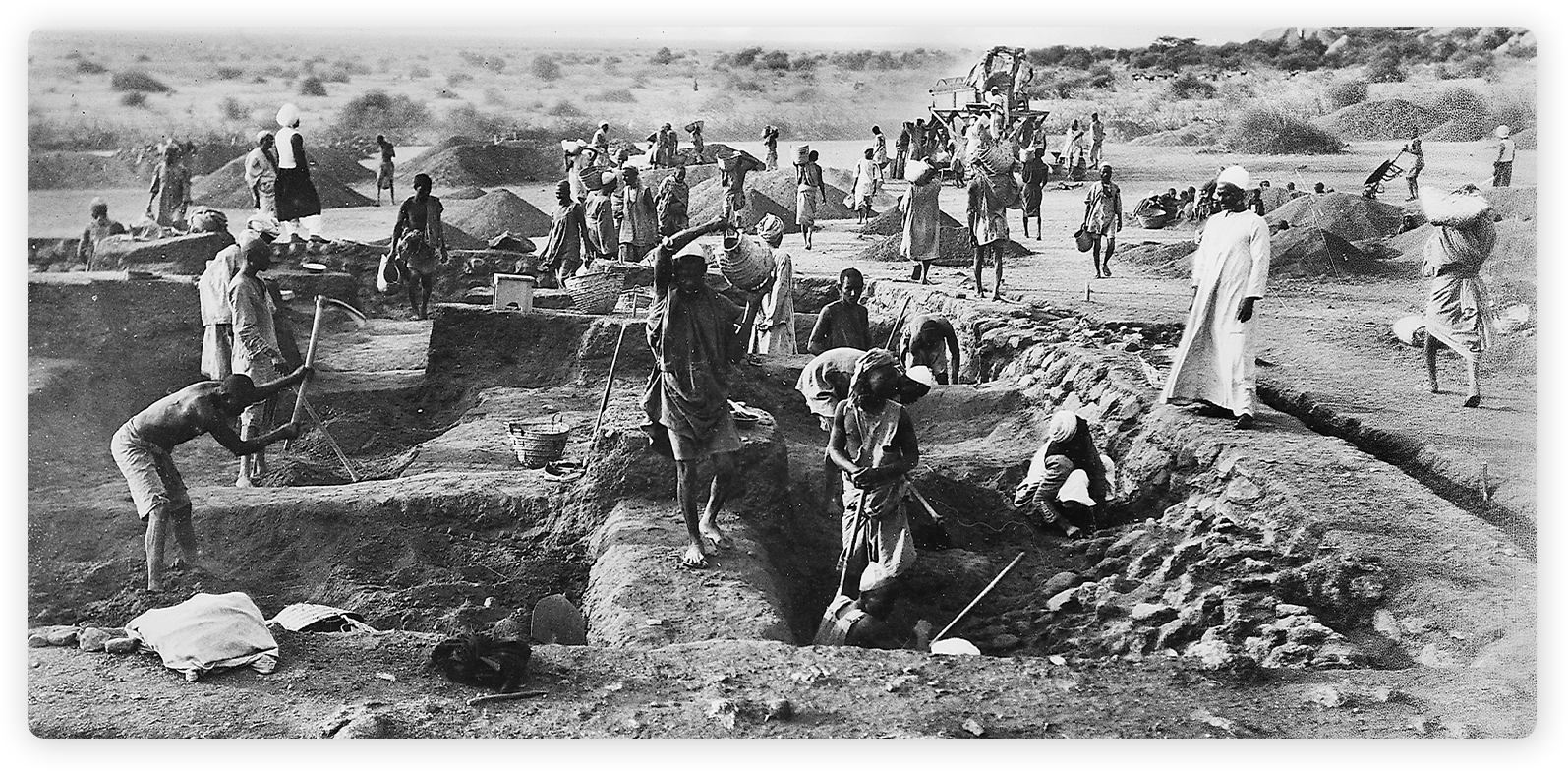

Wellcome excavations in Sudan. Eastern end of one of the ruins uncovered at Saqadi, 1913 (Jebel Moya)

Muslims,

Material Culture and

The Other

A close examination of the Islamic intellectual tradition reveals that, at least theologically, it would be implausible to claim that Muslims have remained indifferent to the past, to the remnants of bygone civilizations, or to material culture. Indeed, the Qur’an explicitly points to the material traces of previous nations as sources of knowledge:

“Have they not traveled through the land and observed how was the end of those before them? They were greater than them in power; they tilled the earth and developed it more than these have done. Their messengers came to them with clear proofs. And Allah would never have wronged them, but they were wronging themselves.” (Surah al-Rum, 30:9)

It is particularly striking that the Qur’an addresses the pre-Islamic Arab society—known as the Jahiliyya period—by urging them to reflect upon archaeological remains. In numerous verses, the Qur’an recounts the fates of nations that once wielded great power. Rather than viewing the relics of ancient civilizations as forbidden or superstitious, the Qur’an commands believers to travel the earth, observe these remnants, and derive lessons from them. Thus, upon closer examination, one may argue that the Qur’anic discourse implicitly supports the preservation of cultural heritage and encourages the transformation of the past into knowledge as a means of moral reflection.

Historically, Muslims have indeed placed value on cultural heritage, not only safeguarding it through practices such as reuse (devşirme) and resettlement (iskân), but also striving to interpret and understand it. Particularly notable is their interest in the archaeological remains of Yemen and Egypt. For instance, al-Hamdani (d. 945) drew images of many nearly forgotten historical structures in Yemen, thereby preserving them for posterity. A further example is the 13th-century work of al-Idrisi (d. 1251), which stands as a testament to medieval Muslim curiosity toward the Egyptian pyramids. His work not only highlights the significance of studying ancient remains but also reflects a systematic and methodological approach to such study. Nevertheless, modern scholarly literature tends to trace the origins of Egyptology to the post-Enlightenment era, often dismissing earlier Muslim contributions. The critique of this neglect is poignantly captured in the title of Okasha El-Daly’s work The Missing Millennium, which challenges the erasure of the Islamic period from the historiography of Egyptology.

Indeed, a review of the literature reveals that most Egyptological studies leap from selective quotations of Greco-Roman sources and the Bible directly to Enlightenment scholarship—entirely bypassing the Islamic centuries. In contrast, a study of medieval Muslim writings shows that scholars of the Islamic world developed a variety of analytical methods, made early attempts to decipher ancient Egyptian scripts, and sought to understand the religious practices, mummification techniques, and administrative structures of ancient Egypt. This evidence challenges the narrative promoted by many Western historians of archaeology who assert that archaeology only emerged as a legitimate field in the 19th century. While it is true that modern archaeology introduced novel techniques—particularly in archaeometry and dating methods—this should not imply a wholesale rejection or neglect of earlier traditions of inquiry.

In fact, this issue extends beyond archaeology to disciplines such as sociology, psychology, and the history of religions. It is often claimed, for example, that the history of religions began with the work of the German philologist Max Müller (d. 1900). However, as early as the 10th century, Muslim scholars made significant contributions to this field. Figures such as Ibn al-Nadīm (d. 995 [?]), al-Bīrūnī (d. 1061 [?]), and al-Shahrastānī (d. 1153) elevated the comparative study of religion to a high intellectual level. Yet, a key distinction must be made between the intellectual encounters that produced these two traditions. The evolution of the social sciences has often been shaped by encounters—whether cooperative or conflictual—between different societies. For Muslims, meaningful interaction with followers of other faiths fostered the production of notable works in the field of religious studies.

By contrast, the 19th-century emergence of the social sciences in the West coincided with the colonial subjugation of non-Western societies. The nature of these encounters fundamentally differed: the Islamic tradition was driven by recognition and acquaintance, whereas the colonial enterprise was motivated by knowledge for the sake of domination. This fundamental difference explains the enduring relevance and reliability of the information provided by scholars like Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Bīrūnī, and al-Shahrastānī concerning other religious traditions. Unfortunately, modern academic discourse often ignores these early Muslim contributions, perpetuating a limited and Eurocentric view of the history of knowledge.

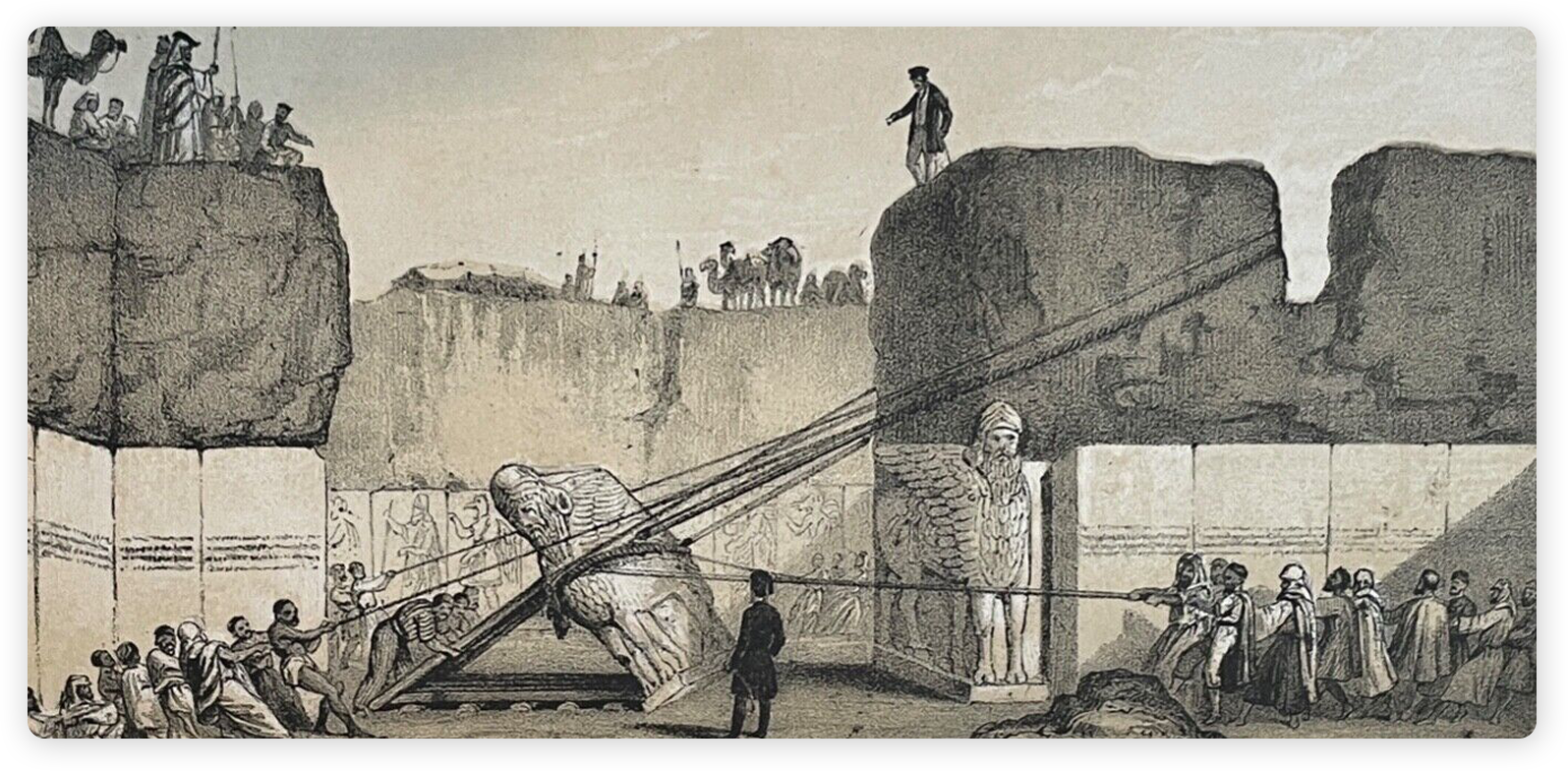

The smuggling of statues found in the Nineveh excavations to England under the leadership of Henry Layard

Plundering the Past

From its very inception in the Western world, archaeology has been intricately linked with colonialism and Orientalism—a connection that is hardly surprising. In the 19th century, European powers viewed virtually all non-European lands as potential colonies. Military expeditions were frequently accompanied by so-called scientific missions. This trend, which began with Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, was soon adopted by other European empires. While armies occupied and exploited the land above, the rich cultural substratum beneath regions such as Mesopotamia and Egypt—areas far more archaeologically fertile than Europe—was subjected to plunder by adventurous, often unscrupulous figures posing as archaeologists or antiquarians. Artifacts removed from these regions were smuggled into Europe through various means and have since begun to be exhibited in some of the world’s most prestigious institutions, such as the British Museum, the Louvre, the Berlin Museum, and museums in Copenhagen.

European interest in archaeology was further fueled by a fascination with biblical geography. The ruins and artifacts brought back from lands referenced in the Bible, along with publications introducing these distant geographies, captivated European audiences. Moreover, imperial powers found in these antiquities a symbolic resource to bolster their claims to civilizational prestige. Competing for global dominance, European states sought to portray themselves as the legitimate heirs of ancient empires. In fact, colonialism was often justified by drawing parallels between modern imperial practices and the ancient expansion of Mesopotamian civilizations. Just as the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians were thought to have disseminated their innovations through conquest, European powers positioned themselves as their modern successors in spreading civilization—again, by way of domination.

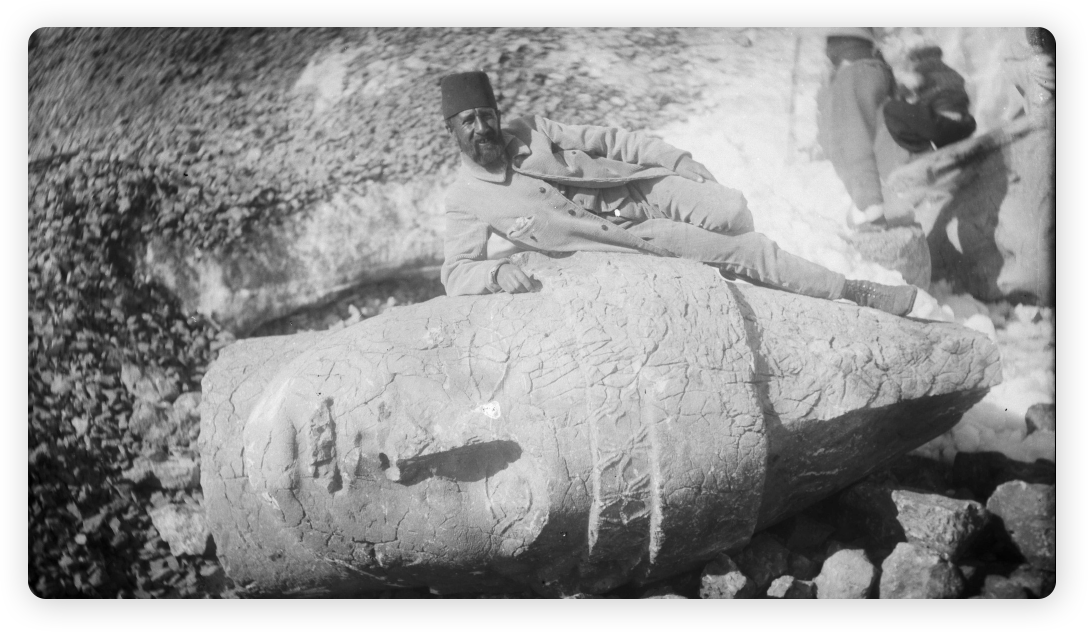

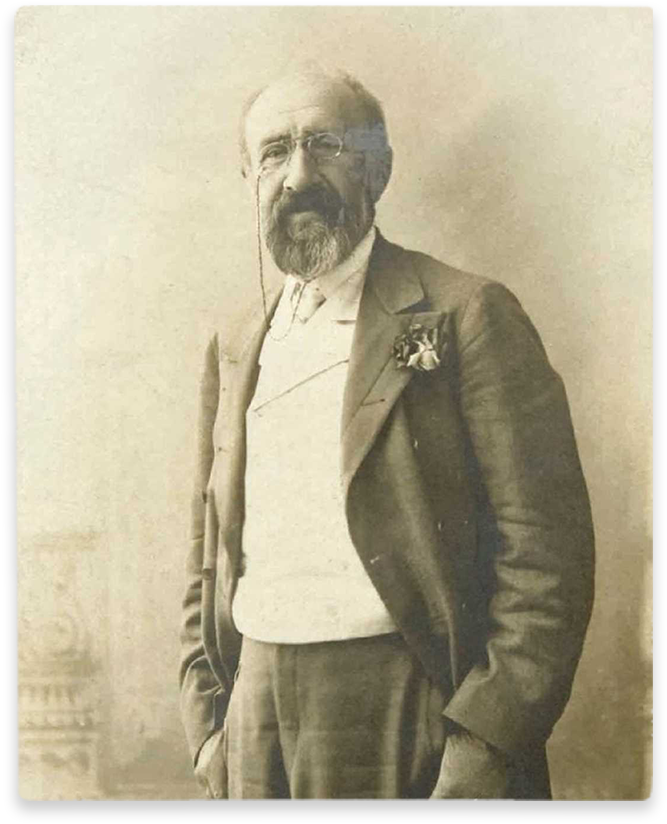

Osman Hamdi Bey at the Lagina excavation together with French archaeologists

Istanbul Archaeological Museums Archive

Portrait of Osman Hamdi Bey

This narrative of continuity helped solidify a Western claim not only to political authority over foreign lands but also to the archaeological and cultural legacies buried within them. Recognizing this exploitation of archaeology as a tool of imperialism, the Ottoman Empire began to take protective measures. Thanks to the initiatives of Osman Hamdi Bey, legal frameworks were established—most notably the promulgation of the Asar-ı Atîka (Antiquities) Regulations—aimed at preventing the illicit export of cultural artifacts. The founding of the Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümâyun) in Istanbul, and later in Jerusalem—particularly as biblical archaeology gained traction—marked further efforts to institutionalize heritage preservation within the Empire. However, these developments elicited negative reactions in European media. The prospect of an Ottoman institution rivaling Western museums sparked discomfort. Western discourse, grounded in the belief that it was both the rightful ruler of the earth’s surface and the custodian of the treasures beneath it, advanced the claim that Eastern societies—past and present—lacked a meaningful connection to material culture and archaeology. According to this worldview, civilization began in Mesopotamia, passed through Egypt and Greece, and ultimately reached its culmination in Europe. Anatolia, within this framework, was depicted merely as a bridge, a conduit for civilizational transmission. Yet subsequent archaeological discoveries have challenged this Eurocentric narrative. Sites such as Göbekli Tepe, Çayönü, and Çatalhöyük reveal that Anatolia was not merely a passageway, but a cradle of advanced and complex human settlement in its own right. These findings clearly illustrate that Eurocentrism was not limited to shaping the modern political order but also played a pivotal role in the very construction and interpretation of the past.

Göbeklitepe Excavation Site, Şanlıurfa

Conclusion

It is difficult to assert that Muslims have fully confronted the profound trauma they experienced in the 19th century—a rupture that spanned political, social, economic, cultural, and intellectual dimensions. The responses that have emerged in an attempt to comprehend this multifaceted rupture often appear partial and fragmented. This, in part, reflects an inadequate grasp of the complexity of the historical moment. Despite being significantly implicated in this historical juncture, Muslims have largely remained indifferent to fields such as material culture, cultural heritage, and archaeology. Yet it is well known that Western hegemony has exerted its influence not only over the present but also in shaping our understanding of the past. This influence is observable in numerous domains, from the inclusion of archaeological sites in World Heritage lists to the interpretative frameworks applied to material culture. It is particularly telling that even the nascent field of “Islamic Archaeology” has emerged primarily from Western academic traditions, with relatively few Muslim scholars engaged in the discipline. The issue at stake, however, is not merely one of scholarly identity, but rather the interpretive paradigms applied to material culture. Similarly, the relationship between Muslims and cultural heritage is often framed through selective and exceptional cases—such as the destruction of the Buddha statues by the Taliban in 2001 or the damage inflicted by ISIS on the ancient city of Palmyra. These acts are frequently interpreted as indicative of a broader Islamic iconoclasm, and at times equated with Byzantine iconoclastic movements. Rather than focusing on a few exceptional cases, attention should be directed to the fact that these artifacts have survived intact for fourteen centuries under Muslim rule. In contrast, the destruction caused by French researchers in Palmyra in their attempt to foreground the Roman heritage, as well as the significant damage inflicted by Israel in Gaza and by the United States in Iraq on cultural heritage, are often overlooked. In sum, it is imperative that Muslims—and indeed all other civilizational spheres—strengthen their relationship with archaeology and cultural heritage. Only through such engagement can a non-colonial and inclusive paradigm be developed, one that embraces the shared past of all humanity. Nations that can liberate their histories from the shadow of colonialism will be better equipped to build futures grounded in intellectual and cultural sovereignty.

İstanbul Archaeological Museum

Çelik, Zeynep. Asar-ı Atika: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Arkeoloji Siyaseti. İstanbul: Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2016.

El-Daly, Okasha. Kayıp Binyıl: İslam Dünyasında Hiyeroglifler ve Eski Mısır. Trans. Ümran Küçükislamoğlu. İstanbul: İthaki Yayınları, 2013.

Flood, Finbarr Barry. “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum.” The Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (2002): 641–659.

Hemdānī, Ahmed b. Yaʿqūb. al-Iklīl. Baghdad, 1980.

Idrīsī, Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. Anwār ʿuluww al-ajrām fī al-kashf ʿan asrār al-ahrām. Frankfurt, 1988.

Mulder, Stephennie. “Imagining Localities of Antiquity in Islamic Societies.” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 6, no. 2 (2017): 229–254.

Toprak, Bilal. Din Arkeolojisi ve Göbekli Tepe. İstanbul: MilelNihal Yayınları, 2020.

Trigger, Bruce. Arkeolojik Düşünce Tarihi. Trans. Fuat Aydın. Ankara: Eskiyeni Yayınları, 2014.

|

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bilal Toprak Bilal Toprak completed his undergraduate and master’s studies at Bursa Uludağ University, and received his PhD from Istanbul University with a dissertation titled “The Possibility of the Archaeology of Religion and Göbekli Tepe.” Between 2016 and 2017, he was a visiting researcher in the Department of Anthropology/Archaeology at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Toprak held academic positions for many years at Mardin Artuklu University and later at Düzce University. He is currently continuing his academic work at the Faculty of Theology at Bandırma Onyedi Eylül University. His research focuses primarily on the archaeology of religion, the relationship between material culture and religion, and belief systems of the ancient world. |

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bilal Toprak

Bilal Toprak completed his undergraduate and master’s studies at Bursa Uludağ University, and received his PhD from Istanbul University with a dissertation titled “The Possibility of the Archaeology of Religion and Göbekli Tepe.” Between 2016 and 2017, he was a visiting researcher in the Department of Anthropology/Archaeology at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Toprak held academic positions for many years at Mardin Artuklu University and later at Düzce University. He is currently continuing his academic work at the Faculty of Theology at Bandırma Onyedi Eylül University. His research focuses primarily on the archaeology of religion, the relationship between material culture and religion, and belief systems of the ancient world.