The Season of Ramadan

İskender Pala

Ramadan Writings I

The Season of Ramadan

İskender Pala

In Islamic belief, the month of Ramadan is associated with forgiveness, divine grace, and benevolence. We all believe that during this month, no outstretched hand will be turned away empty, hearts will be filled with joy, and faces will glow with smiles. Every fasting believer knows that, alongside the joy and peace of iftar (the evening meal to break the fast), the blessings of suhoor (the pre-dawn meal) bring happiness and contentment. Fasting is for Allah, and its reward will be granted by Allah Himself. This is why, during this month, believers are joyful, hypocrites are sorrowful, and Satan is chained and distraught. The gates of Paradise are open, the gates of Hell are closed, and the believer ascends to an angelic state. Just as humans are the most honorable of creations, Ramadan is the most virtuous of months. It is the sultan of the eleven months, welcomed with “Welcome, O Ramadan!” and bid farewell with “Farewell, O month of forgiveness!” It is the joy, hope, and celebration of the believers. This is why people begin preparations even before Ramadan arrives, ensuring that this month is observed with special care and sensitivity.

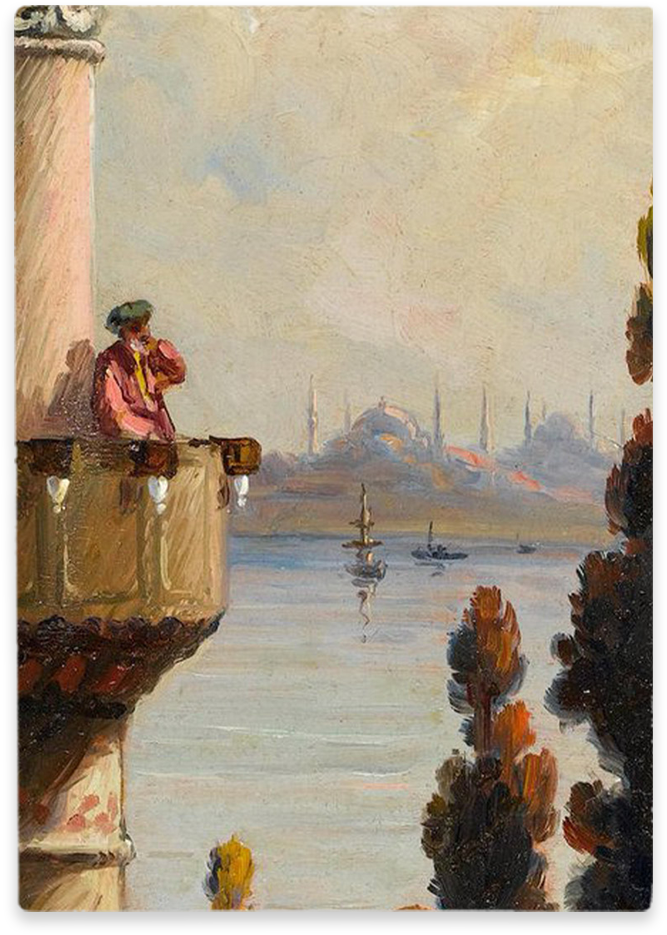

But what about the old days, the Ramadans of the past? I do not believe that what is written in old books about the Ramadans experienced in a homogeneous Islamic society is sufficient. Rather than what I have read about the Ramadans of the recent past, I wonder how blissful it would have been to live in Istanbul during one of the unspoiled Ramadans of the distant past. When poets describe these times, it feels as though the veil of imagination is about to tear. The abundance of couplets in thick divans that mention fasting, Ramadan, and Eid is enough to show that the Ramadans of old left their mark on every passing and future year. Of course, the poet is part of this life and is inevitably influenced by fasting, iftar, Ramadan, and Eid. For example, one poet laments:

Günümüz gün gibi türlü zevâl ile geçer

Kadrimiz bilmediler nite ki mâh-ı ramazân

Yahya Bey

Our days pass like the sun, with various declines (i.e., heartbreaks in love).

Just as they did not know the value of Ramadan, they did not know ours. What can one do?

This is truly a magnificent couplet! It is a subtle way of boasting while complaining about being undervalued. The poet appears to criticize himself while actually praising himself (a rhetorical device known as ta’kid al-madh bi-ma yushbih al-dhamm). No matter how much a believer worships during Ramadan, they still cannot fully appreciate its value, for the virtues of this month are boundless. Wise people, aware of this, constantly lament their inability to fully grasp the significance of Ramadan. Especially the Night of Power (Laylat al-Qadr), which is better than a thousand months! When the poet says, “They did not know our value,” he is also subtly alluding to the uncertainty of which night is the Night of Power, employing a clever play on words (tawriya).

In almost every household where fasting is observed, there is a visible abundance during Ramadan. By Allah’s grace and wisdom, Ramadan is a month of plenty. Here is a poetic dialogue between two individuals:

Dedim artırdı gamın hânını hicrin gecesi

Dedi nimet çoğ olur çünki şeb-i rûze gele

Ahmet Paşa

I said, ‘The night of separation has increased the sorrow of your absence.’

He replied, ‘Of course, blessings multiply when the night of fasting arrives.’

For the old poets, the first thing that comes to mind when Ramadan is mentioned is longing, separation, and heartbreak. There is little difference between the fasting person waiting for iftar and the lover (the poet) waiting for their beloved. Especially if this waiting culminates in Eid (reunion)! Observe what Fatih says:

Zülfün şeb-i kadr oldu kaşın ıyd hilâli

Vaslın demi ıyd oldu firâkın ramazândır

Avnî

Your hair is the Night of Power, your brow the crescent of Eid.

Your union is the time of Eid, your separation is Ramadan

Now let us see Hayâlî’s imagination:

Aynısın lâmın otuz gün olduğuna müzenin

Ya felek levhinde nûn-ı dâmen-i Rahmân mısın

Are you the ‘ayn-lām’ because fasting lasts thirty days?

Or are you the ‘nūn’ at the end of the word ‘Rahman’ on the celestial sphere

The poet first implies that the letter “lām” in the abjad system equals 30, then combines the letters “nūn-ayn-lām” to form the word “na’l” (a branding wound), suggesting that his heart is torn and wounded from longing for his beloved during the fast. Finally, he desires reunion, symbolized by the crescent of Eid. Such imagination deserves admiration: “Modesty and decorum!”

In a repetitive murabba, Aşkî describes the final days of Ramadan in the 16th century with sincere emotions, without exaggeration. Here is one stanza:

On bir aylık râhdan gelmiştin ey mâh-ı sâik

Eylemişti pertevin halkın günâhın nâ-bedîd

İsmetinle ağzına İblis’in urmuştun kilid

Elvedâ ey mâh-ı rûze merhabâ ey rûz-ı ıyd

Aşkî

O blessed month, you came from an eleven-month journey.

Your light erased the sins of the people.

With your purity, you locked the mouth of Satan.

Farewell, O month of fasting; welcome, O day of Eid!

Speaking of Eid, let us also recall that in the past, taverns were completely closed during Ramadan (thankfully, some still close out of respect for Ramadan today!) and reopened as soon as Eid arrived. Tavern keepers even prepared silk shawls as gifts for the first customer on Eid. (Surely, many drunkards rushed to the tavern doors after Eid prayers to claim this prize.) Although Ahmet Paşa was not one of the drunkards, he expressed the official closure of taverns during Ramadan as follows:

Çektim firâkın savmını, erdim cemâlin iydine

Aç leblerin meyhânesin ney gibi nâlân et beni

Ahmet Paşa

I endured the fast of separation and reached the Eid of your beauty.

Now open the tavern of your lips and make me lament like a reed flute.

In our history, Ramadan jokes and pranks are also famous. Here are some couplets of that kind:

Olmayam şâhid ü meysiz bir an

Niyyetim çok hele çıksın ramazân

Şâmî

I cannot be beautiful or without wine for even a moment.

My intention is strong—just let Ramadan end!

Gündüz çıkarır zevkini rindân ramazanım

İftâr safâsın dahi ehl-i şikem eyler

Neş’et

During the day, the revelers enjoy Ramadan.

The pleasure of iftar is for the gluttons.

The revelers enjoyed Ramadan during the day. Otherwise, the pleasure of iftar belongs to the gluttonous hypocrites. Note that the revelers’ enjoyment involved breaking the fast! As they asked a Bektashi:

-Do you like the fast, O dervish?

-Of course I do, because it is eaten.

In short, it seems that among our ancestors, there were those who enlivened Ramadan and those who ruined it. Just like today! But back then, the proportion of those who enlivened it was likely higher.

In Islamic belief, the month of Ramadan is associated with forgiveness, divine grace, and benevolence. We all believe that during this month, no outstretched hand will be turned away empty, hearts will be filled with joy, and faces will glow with smiles. Every fasting believer knows that, alongside the joy and peace of iftar (the evening meal to break the fast), the blessings of suhoor (the pre-dawn meal) bring happiness and contentment. Fasting is for Allah, and its reward will be granted by Allah Himself. This is why, during this month, believers are joyful, hypocrites are sorrowful, and Satan is chained and distraught. The gates of Paradise are open, the gates of Hell are closed, and the believer ascends to an angelic state. Just as humans are the most honorable of creations, Ramadan is the most virtuous of months. It is the sultan of the eleven months, welcomed with “Welcome, O Ramadan!” and bid farewell with “Farewell, O month of forgiveness!” It is the joy, hope, and celebration of the believers. This is why people begin preparations even before Ramadan arrives, ensuring that this month is observed with special care and sensitivity.

But what about the old days, the Ramadans of the past? I do not believe that what is written in old books about the Ramadans experienced in a homogeneous Islamic society is sufficient. Rather than what I have read about the Ramadans of the recent past, I wonder how blissful it would have been to live in Istanbul during one of the unspoiled Ramadans of the distant past. When poets describe these times, it feels as though the veil of imagination is about to tear. The abundance of couplets in thick divans that mention fasting, Ramadan, and Eid is enough to show that the Ramadans of old left their mark on every passing and future year. Of course, the poet is part of this life and is inevitably influenced by fasting, iftar, Ramadan, and Eid. For example, one poet laments:

Günümüz gün gibi türlü zevâl ile geçer

Kadrimiz bilmediler nite ki mâh-ı ramazân

Yahya Bey

Our days pass like the sun, with various declines (i.e., heartbreaks in love).

Just as they did not know the value of Ramadan, they did not know ours. What can one do?

This is truly a magnificent couplet! It is a subtle way of boasting while complaining about being undervalued. The poet appears to criticize himself while actually praising himself (a rhetorical device known as ta’kid al-madh bi-ma yushbih al-dhamm). No matter how much a believer worships during Ramadan, they still cannot fully appreciate its value, for the virtues of this month are boundless. Wise people, aware of this, constantly lament their inability to fully grasp the significance of Ramadan. Especially the Night of Power (Laylat al-Qadr), which is better than a thousand months! When the poet says, “They did not know our value,” he is also subtly alluding to the uncertainty of which night is the Night of Power, employing a clever play on words (tawriya).

In almost every household where fasting is observed, there is a visible abundance during Ramadan. By Allah’s grace and wisdom, Ramadan is a month of plenty. Here is a poetic dialogue between two individuals:

Dedim artırdı gamın hânını hicrin gecesi

Dedi nimet çoğ olur çünki şeb-i rûze gele

Ahmet Paşa

I said, ‘The night of separation has increased the sorrow of your absence.’

He replied, ‘Of course, blessings multiply when the night of fasting arrives.’

For the old poets, the first thing that comes to mind when Ramadan is mentioned is longing, separation, and heartbreak. There is little difference between the fasting person waiting for iftar and the lover (the poet) waiting for their beloved. Especially if this waiting culminates in Eid (reunion)! Observe what Fatih says:

Zülfün şeb-i kadr oldu kaşın ıyd hilâli

Vaslın demi ıyd oldu firâkın ramazândır

Avnî

Your hair is the Night of Power, your brow the crescent of Eid.

Your union is the time of Eid, your separation is Ramadan

Now let us see Hayâlî’s imagination:

Aynısın lâmın otuz gün olduğuna müzenin

Ya felek levhinde nûn-ı dâmen-i Rahmân mısın

Are you the ‘ayn-lām’ because fasting lasts thirty days?

Or are you the ‘nūn’ at the end of the word ‘Rahman’ on the celestial sphere

The poet first implies that the letter “lām” in the abjad system equals 30, then combines the letters “nūn-ayn-lām” to form the word “na’l” (a branding wound), suggesting that his heart is torn and wounded from longing for his beloved during the fast. Finally, he desires reunion, symbolized by the crescent of Eid. Such imagination deserves admiration: “Modesty and decorum!”

In a repetitive murabba, Aşkî describes the final days of Ramadan in the 16th century with sincere emotions, without exaggeration. Here is one stanza:

On bir aylık râhdan gelmiştin ey mâh-ı sâik

Eylemişti pertevin halkın günâhın nâ-bedîd

İsmetinle ağzına İblis’in urmuştun kilid

Elvedâ ey mâh-ı rûze merhabâ ey rûz-ı ıyd

Aşkî

O blessed month, you came from an eleven-month journey.

Your light erased the sins of the people.

With your purity, you locked the mouth of Satan.

Farewell, O month of fasting; welcome, O day of Eid!

Speaking of Eid, let us also recall that in the past, taverns were completely closed during Ramadan (thankfully, some still close out of respect for Ramadan today!) and reopened as soon as Eid arrived. Tavern keepers even prepared silk shawls as gifts for the first customer on Eid. (Surely, many drunkards rushed to the tavern doors after Eid prayers to claim this prize.) Although Ahmet Paşa was not one of the drunkards, he expressed the official closure of taverns during Ramadan as follows:

Çektim firâkın savmını, erdim cemâlin iyine

Aç leblerin meyhânesin ney gibi nâlân et beni

Ahmet Paşa

I endured the fast of separation and reached the Eid of your beauty.

Now open the tavern of your lips and make me lament like a reed flute.

In our history, Ramadan jokes and pranks are also famous. Here are some couplets of that kind:

Olmayam şâhid ü meysiz bir an

Niyyetim çok hele çıksın ramazân

Şâmî

I cannot be beautiful or without wine for even a moment.

My intention is strong—just let Ramadan end!

Gündüz çıkarır zevkini rindân ramazanım

İftâr safâsın dahi ehl-i şikem eyler

Neş’et

During the day, the revelers enjoy Ramadan.

The pleasure of iftar is for the gluttons.

The revelers enjoyed Ramadan during the day. Otherwise, the pleasure of iftar belongs to the gluttonous hypocrites. Note that the revelers’ enjoyment involved breaking the fast! As they asked a Bektashi:

-Do you like the fast, O dervish?

-Of course I do, because it is eaten.

In short, it seems that among our ancestors, there were those who enlivened Ramadan and those who ruined it. Just like today! But back then, the proportion of those who enlivened it was likely higher.

FASTING ODDITIES

Fasting and humor have, for some reason, been like twin siblings since ancient times. In fact, the religious and psychological aspects of this are a research topic in themselves. To what extent is humor permissible for a fasting person? What should the limits of humor be? Why does humor appeal more to those who are fasting? These questions can be multiplied. However, from the Ottoman period onward, the corrupted Janissary-Bektashi tradition seems to trivialize fasting. We all know or have heard a few Bektashi jokes that begin with “O dervishes!” and are related to Ramadan.

Setting all this aside for now, I would like to bring together strange fasting stories and literary figures. But first, I intend to share a memory with you.

I do not know if this is still practiced in Anatolia, but during my childhood Ramadans, I used to become a “fasting tycoon.” How? Let me explain:

When I was about 8 or 10 years old, I would wake up for suhoor every night and intend to fast like the adults in my family. By midday, I would get hungry, wandering around the pantry like a calf tied to a short rope, turning pale as I gazed at the food. At that moment, my mother or father would take pity on me and come to my rescue, making me an offer:

-My dear child, why don’t you sell me your fast?

As if I were not hungry at all, I would start bargaining, sometimes selling my fast for five kurus (a significant amount back then), sometimes for a biscuit sandwich, sometimes for a pair of shoes, and sometimes for a new pair of pants made from my older brother’s old ones. I remember that through this, I earned both my Eid clothes and my Eid pocket money with the sweat of my fasting. Those were such delightful days!

I believe almost everyone has experienced some form of fasting bargaining. Muslim Turks have found such appealing ways to accustom their children to prayer and fasting. Buying a child’s innocent fast in exchange for a gift and encouraging them in this way is not only a health measure but also a great lesson in pedagogy.

The poet Sâbit has a rather strange couplet:

Za’f ile hilâl eylemiş ol mâh-ı cihanı

Vaslına ermiş iken yiye yazdım ramazânı

With weakness, that world-moon has turned into a crescent.

Though I reached union, I nearly ate Ramadan.

Truly, one must applaud such sharp-witted poets who find legal loopholes to break the fast. This couplet is more like a Bektashi joke.

Nesîmî has a couplet that goes:

Gel gel berû ki savm u salâtın kazâsı var

Sensiz geçen zamân-ı hayâtın kazâsı yok

Come, come, for the makeup of fasting and prayer exists.

But the time of life spent without you has no makeup.

Had Nesîmî not been flayed for his divine love, we might have considered this statement a crime. Let him be blessed in his love!

And here is a joke:

In history, the Keçecizâde family is known for their wit. İzzet Molla, may he rest in peace, was not only witty but also quite (and by quite, I mean very) overweight. One evening, he was invited to a friend’s mansion for iftar. In those days, it was customary to sit down for the meal after the evening prayer. The iftar cannon fired, and the fasts were opened with zamzam water, etc., before the prayer began. At that moment, a new guest arrived, breathless, and seeing that the others had started praying, he quickly removed his socks and rolled up his sleeves. The water jug and basin were brought for him to perform ablution. Meanwhile, the evening prayer is short, with minimal additional recitations. The imam was also in a hurry, reciting quickly and keeping the bowing and prostrations brief. Molla struggled to keep up with the imam. The guest, preparing for ablution, called out to the water bearer:

-My son, hurry up. Let us perform ablution and catch up with the imam.

Observing this from within the prayer, Molla could not resist murmuring loud enough for the guest to hear:

-Sir, no need to hurry! We cannot keep up with this imam while inside the prayer; how will you catch up from outside?

|

İskender Pala Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.” With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak. His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages. Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies. |

İskender Pala

Born in 1958 in Uşak, İskender Pala graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Literature in 1979. He earned his doctorate in Divan literature in 1983, became an associate professor in 1993, and was awarded the title of professor in 1998. To rekindle public interest in Divan literature, he wrote articles, essays, stories, and newspaper columns inspired by classical poetry. His seminars and conferences were widely followed, earning him the title “The Man Who Made Divan Poetry Loved.”

With his significant contributions to literature, he has received numerous prestigious awards, including: The Turkish Writers’ Association Language Award (1989), The AKDTYK Turkish Language Institution Award (1990), The Turkish Writers’ Association Research Award (1996). Additionally, in 2001, he was named “People’s Hero” by the citizens of Uşak.

His literary works, including Babil’de Ölüm İstanbul’da Aşk (Death in Babylon, Love in Istanbul), Katre-i Matem (The Drop of Mourning), Şah & Sultan (Shah & Sultan), OD, Efsane (The Legend), Mihmandar, Karun ve Anarşist (Karun and the Anarchist), Abum Rabum, İtiraf (The Confession), Akşam Yıldızı (The Evening Star), Kervan (The Caravan), A-71, Surnâme, Aşk Hikâyesi (A Love Story) and Azdahaki have been widely acclaimed, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers and being translated into multiple languages.

Recognizing his influence, the Turkish Patent Institute registered his name as a trademark. He was also honored with the Presidential Grand Award of the Republic of Turkey in 2013 and received the Turkish World TURKSOY Honor Medal in 2023. Considering Bülbülün Kırk Şarkısı (The Nightingale’s Forty Songs) as the most meaningful work of his career, İskender Pala is married with three children. In addition to being a faculty member at Istanbul Kültür University, he serves as a member of the Turkish Presidency’s Council on Culture and Arts Policies.