Understanding the Spirit of the

Sharḥ Tradition

Charperdī’s Tatimmat al-Kashshāf as a Classic Example of Qur’anic Commentary

M. Taha Boyalık

Understanding the Spirit of the Sharḥ Tradition

Charperdī’s Tatimmat al-Kashshāf as a Classic Example of Qur’anic Commentary

M. Taha Boyalık

In classical writing culture, the value of a text is not determined solely by the era in which it was composed, but rather by the attention and interpretive activity it receives from subsequent generations. One of the most enduring and productive forms of such activity is the tradition of sharḥ (commentary), which is not merely an effort to explain or simplify a text. More often, it signifies the establishment of a profound intellectual engagement with the source text—rethinking it, and reinterpreting it in light of the needs of a new era. In the history of Islamic thought, this tradition has gone beyond serving as a pedagogical tool; it has evolved into a form that cultivates intellectual discipline and ethical reasoning. Indeed, a sharḥ authored by a theologian (mutakallim), grammarian (naḥwī), exegete (mufassir), or logician (manṭiqī) not only analyzes the foundational text but also reveals the commentator’s scholarly perspective, their dialogical relationship with the tradition, and how they reformulate that tradition. In this regard, the sharḥ tradition tends to coalesce around canonical texts: these works are meticulously examined word by word, their meanings are scrutinized, critiqued, and enriched through reinterpretation in response to contemporary intellectual concerns.

The period between the 7th and 13th centuries AH (13th to 19th centuries CE), during which sharḥ practices became institutionalized and acquired a defining character, may be described as the “Late Classical Period” in the Islamic intellectual tradition. During this phase, the production of shurūḥ (commentaries) and ḥawāshī (marginal glosses) began to outpace the composition of original treatises (taʾlīf). A primary reason for this shift was the maturation and systematization of the major Islamic sciences, which had by then reached a stage of intellectual refinement and internal stability. Following the passing of the Prophet Muhammad, the Muslim community underwent a series of turbulent transitions. The intellectual responses to these challenges gradually crystallized in the form of the linguistic and religious sciences. Muslim encounters with diverse religious and cultural environments, coupled with exposure to the legacy of Ancient Greek thought from the 2nd/8th century onward, accelerated the development of various disciplines. This formative stage extended up to the late 5th/11th century and is referred to as the “Early Classical Period,” marked by intense and multifaceted intellectual contestations. By the onset of the Late Classical Period, the foundational tensions that once defined the trajectories of Islamic thought—such as those between the ahl al-ḥadīth and ahl al-raʾy, grammarians and logicians, theologians and philosophers, mystics and jurists—had lost their defining force. In their place emerged more reconciliatory approaches and comprehensive syntheses. The classical texts that shaped this era, along with their abridged (ikhtiṣār), systematized (tartīb), and refined (tahdhīb) versions, captured the intellectual arc of their respective traditions in condensed form. In doing so, they laid a robust foundation for the flourishing of the sharḥ tradition.

An overall progressive reading of the Late Classical Period—and more specifically of the sharḥ activities that defined this era—has often led to reductive analyses divorced from historical reality. In our view, the tendency to interpret the sharḥ tradition, which gained significant momentum during the Late Classical Period, as a symptom of “intellectual stagnation” or the “end of original thought” reflects a superficial reading that fails to consider the complexity of the historical and scholarly dynamics at play. In truth, the predominance of commentary over original treatise (taʾlīf) writing during this period signals not intellectual decline, but rather the maturation of traditional Islamic sciences within a coherent paradigm—an indication that these disciplines had reached their structural limits in terms of what they could offer to Islamic thought and society at the time. To denigrate the sharḥ tradition on the grounds of a lack of original composition during an era in which the conditions for paradigm shifts had not yet fully matured is a misplaced critique. By the Late Classical Period, the traditional linguistic, religious, and metaphysical sciences had already developed their theoretical frameworks in accordance with their own internal contexts and problematics. Thus, the sharḥ activities of this period may be seen as the final stage in the formation, development, and consolidation of these intellectual traditions. In this light, both the claims that shurūḥ and ḥawāshī are mere repetitions lacking originality, and the opposing view that they serve as near-magical keys capable of resolving even contemporary issues, are devoid of scholarly merit. The sharḥ–ḥāshiya tradition of the Late Classical Period must be approached not through sweeping affirmations or dismissals, but through a rigorous, scholarly lens.

My own engagement with the tafsīr sharḥ–ḥāshiya tradition was largely shaped by such considerations. Specifically, through my prior intensive readings in the al-Kashshāf tradition, I came to recognize that independent exegetical works composed in the stylistic lineage of al-Kashshāf or Anwār al-Tanzīl rarely offered as much intellectual contribution as the shurūḥ written on those texts. When composed using similar methods, original treatises frequently fell into repetition, whereas the sharḥ form allowed scholars to contribute insights without redundancy. Indeed, when one considers the exegetical traditions surrounding al-Kashshāf and Anwār al-Tanzīl, it becomes evident that the highest level of refinement achieved within mainstream traditional Qur’anic exegesis found its most complete expression in the form of commentaries. At the same time, it should also be acknowledged that, in terms of original composition, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s al-Tafsīr al-Kabīr occupies a singular and unparalleled position in the application of traditional exegetical methodologies.

In sum, within the intellectual boundaries of traditional tafsīr, the commentaries written during the Late Classical Period clearly hold a significant place. Nearly a decade ago, while pursuing my studies on the al-Kashshāfcorpus, I realized the critical importance of producing scholarly editions (taḥqīq) in order to replace prevailing generalizations about the sharḥ tradition with more rigorous academic assessments. Motivated by this realization, I undertook several editorial initiatives.

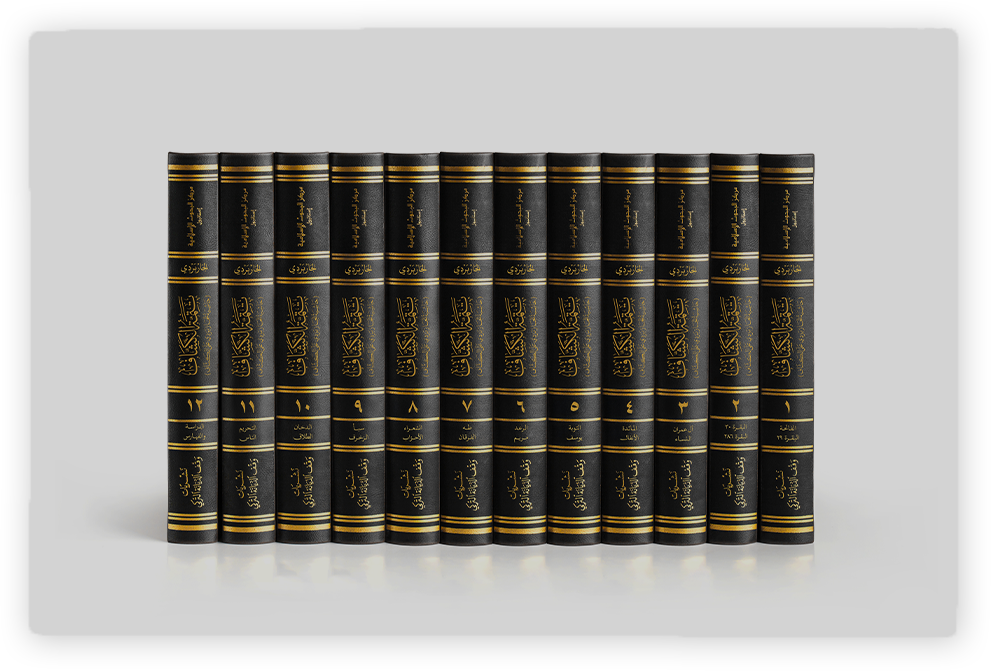

When these convictions aligned with the objectives of the TDV Center for Islamic Studies’ Late Classical Period Project, we launched a critical edition project of Charperdī’s Tatimmat al-Kashshāf, a foundational commentary on al-Kashshāf, as a starting point for renewed scholarly engagement with the tradition of Qur’anic commentary. The work, prepared as a twelve-volume edition through a collective academic effort, includes the full text of al-Kashshāf and features a dual-layered page design. This first-ever critical edition of a classical sharḥ on al-Kashshāf will offer valuable contributions to the still-nascent academic field of tafsīr sharḥ–ḥāshiya studies.

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Chārpardī and the Composition Process of His Commentary

Fakhr al-Dīn Abū al-Makārim Aḥmad b. Ḥasan b. Yūsuf, better known by his nisba as al-Chārpardī, was born in the village of Chārpard near Tabriz in 664/1265–66, according to the report of the Baghdadi bibliographer Ismāʿīl Pasha. Most biographers record his death in 746/1346. During Chārpardī’s lifetime, Tabriz served as the political capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty, established by the Mongol ruler Hülegü. The Ilkhanid elite’s patronage of scholars, coupled with the scholars’ efforts to Islamize the ruling class, transformed the city into a vibrant intellectual center. It was during this period that al-Bayḍāwī moved from Shiraz to Tabriz (in either 680 or 681/1281–82), where he spent the final decade of his life. During this time, Chārpardī—then in his twenties—became his student. It is therefore reasonable to assume that Bayḍāwī’s influence played a significant role in shaping Chārpardī’s interest in Qur’anic exegesis, particularly in his focus on al-Kashshāf.

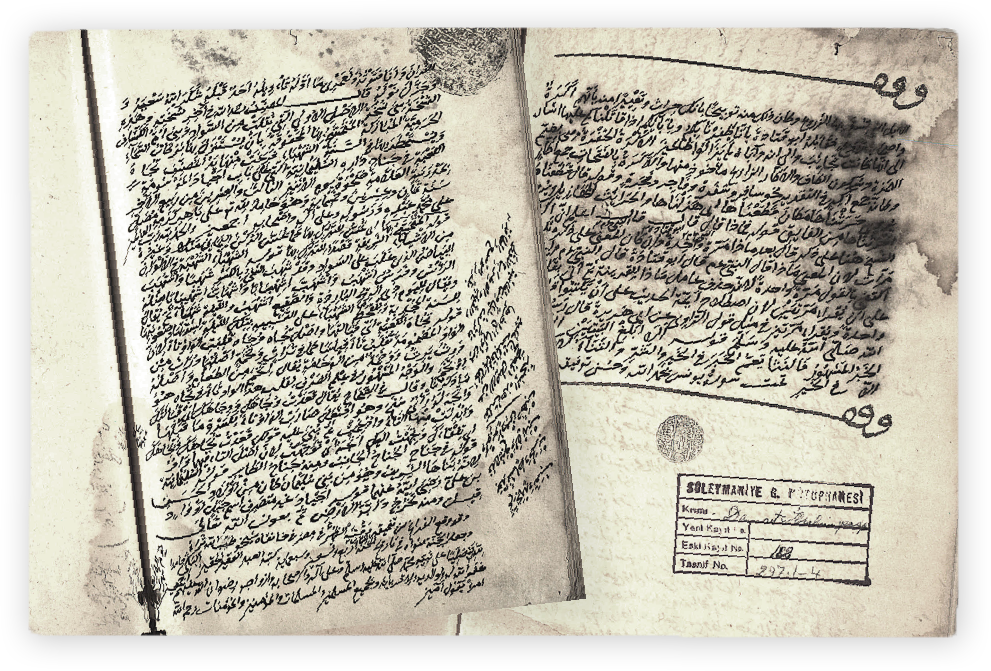

The genesis of Chārpardī’s commentary on al-Kashshāf began with marginal notes he inscribed on his personal copy of the text. Likely composed in conjunction with his teaching activities, these annotations were eventually organized and expanded—at the urging of his students—into a comprehensive and independent commentary covering the entirety of al-Kashshāf. After completing the draft manuscripts of the work, Chārpardī began the process of producing a clean copy (tabyīḍ), but he was only able to carry this out up to verse 2:197 (al-Baqara). According to notes found in one manuscript, the remaining sections were copied from Chārpardī’s draft version by his students. As such, in the parts of the commentary not reviewed by the author, one can occasionally find redundant phrases or passages that require correction.

It is not known precisely when Chārpardī completed his sharḥ of al-Kashshāf. However, one extant manuscript containing the marginal draft notes on al-Kashshāf is dated 734/1333–34. Furthermore, it has been established that Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tībī (d. 743/1342) made use of Chārpardī’s commentary in his own work, Futūḥ al-ghayb, which was completed before 735/1334–35. Even if a finalized version of Chārpardī’s sharḥ does not survive, the existence of these references suggests that at least the draft version must have been completed by that time. Prior to Tatimmat al-Kashshāf, the works composed on al-Kashshāf were either in the form of abridgments (mukhtaṣarāt) or centered primarily on critique—especially targeting Muʿtazilī elements—rather than offering direct exposition. In this respect, Tatimmat al-Kashshāf stands out as the first commentary to encompass the entire al-Kashshāf, one that does not privilege polemical critique in theological matters, but instead seeks to provide clear and systematic explanation.

Tatimmat al-Kashshāf and Methodological Structure

In the history of Islamic sciences, the periods during which classical works suitable for commentary (sharḥ) began to be composed varied from one discipline to another. For instance, al-Kitāb, the foundational classic of Arabic grammar (naḥw), was written as early as the 2nd/8th century, and commentaries on it began to appear in the following century. In the field of Qur’anic exegesis (tafsīr), however, the sharḥ tradition developed relatively late—emerging toward the end of the 7th/13th century, particularly with the commentaries written on al-Zamakhsharī’s (d. 538/1144) al-Kashshāf. Setting aside a few earlier commentaries on tafsīr works, it can be said that al-Kashshāf served as the primary catalyst for the emergence of the sharḥ–ḥāshiya tradition in Qur’anic exegesis.

Completed in 528/1134 after a two-year writing process, al-Kashshāf generated considerable enthusiasm among Muʿtazilī circles, especially in regions such as the Ḥijāz and Khwārazm, where the school maintained influence at the time. Due to its uncompromising application of Muʿtazilī hermeneutic principles, the work initially failed to gain comparable attention within Sunnī scholarly circles. Consequently, during the century and a half following the Muʿtazila’s waning influence, al-Kashshāf received relatively little scholarly attention, aside from a few exceptional cases. This cautious Sunnī reception began to shift in the early 8th/14th century, when the work began to attract significant scholarly interest. One of the turning points in this shift was the exegetical approach adopted by al-Bayḍāwī (d. 691/1291–92), a prominent figure in Sunnī scholarship. In his tafsīr Anwār al-Tanzīl, Bayḍāwī frequently relied on al-Kashshāf as a principal source—systematically comparing his own interpretations with it and, in many places, presenting a condensed version of it—while reworking its Muʿtazilī content to align with Sunnī orthodoxy. Bayḍāwī’s methodological choice confirmed the status of al-Kashshāf as an indispensable reference for the application of grammatical and rhetorical (balāgha) tools in Qur’anic interpretation. Following Bayḍāwī, commentaries on al-Kashshāf increasingly emphasized explanatory clarity over theological critique. The first comprehensive explanatory shurūḥ were composed in Tabriz, the very city where Bayḍāwī had spent many years engaged in teaching. Among the leading scholars of this trend was his student, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Chārpardī, who played a pioneering role in this development.

At the beginning of his work, Chārpardī states that he composed this text as a tatimma (supplement) to al-Kashshāf. He notes that he will clarify the contentious issues found in al-Kashshāf, explain the lexical meanings of words, analyze sentence structures, comment on poetic verses, identify views that contradict Sunnī doctrine and present the correct interpretation, address certain iʿrāb (grammatical) possibilities and semantic subtleties neglected in al-Kashshāf, and distinguish among the recitations (qirāʾāt) mentioned in the text by identifying those belonging to the canonical seven and separating them from the anomalous (shādh) ones, as well as referencing additional recitations not mentioned in the original. In addition to these points explicitly stated by the shāriḥ himself, one of the notable features of the work is its effort to identify different transmitted versions of the al-Kashshāf text and offer informed preferences among them. Another distinctive aspect is that the commentary serves as a bridge between al-Kashshāf and Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s al-Tafsīr al-Kabīr. On numerous occasions, the shāriḥ supplements the al-Kashshāf text with lengthy quotations—sometimes spanning entire pages—from Rāzī’s work, aiming to complete Zamakhsharī’s interpretations through Rāzī’s methodological lens.

Chārpardī’s principal source in tafsīr is unquestionably Rāzī’s al-Tafsīr. Another regularly cited work is al-Wāḥidī’s al-Tafsīr al-Wasīṭ. Beyond these, Chārpardī draws from a wide range of commentaries, including al-Farrāʾ’s Maʿānī al-Qurʾān and al-Kawāshī’s Tafsīr. In the field of lexicography, Chārpardī refers to a continuum of scholars ranging from Khalīl b. Aḥmad to al-Zamakhsharī; in grammar (naḥw), from Sībawayh to Ibn al-Ḥājib; in rhetoric (balāgha), from al-Jurjānī to al-Sakkākī; and in jurisprudence, primarily within the Shāfiʿī school, from al-Māwardī to al-Nawawī. As for ḥadīth, Chārpardī typically transmits reports through existing tafsīr works. Nevertheless, he also consults major collections such as the Ṣaḥīḥayn, al-Baghawī’s Masābīḥ al-Sunna, and Ibn al-Athīr’s Jāmiʿ al-Uṣūl. Regarding the science of Qur’anic recitation, his most frequently cited source is Abū ʿAlī al-Fārisī’s al-Ḥujja. He also references works by numerous other qirāʾa scholars, including al-Dānī and al-Sajāwandī. Since Chārpardī does not deeply engage in theological debates, it is difficult to identify a defined corpus of sources in the field of kalām. However, within the limited scope of his critiques of Muʿtazilī views, he makes occasional references to Ibn al-Munayyir’s al-Intiṣāf.

Chārpardī’s Tatimmat al-Kashshāf, as the first complete and comprehensive commentary on al-Kashshāf, became one of the most foundational sources within the al-Kashshāf sharḥ–ḥāshiya tradition. Numerous subsequent commentaries on al-Kashshāf cite this work regularly. It served as a principal reference for prominent commentators such as Fāḍil al-Yamanī, al-Tībī, Sirāj al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī, and al-Bābartī. Moreover, it has been established that even later exegetes such as Kemālpāşazāde and Taşköprizāde benefited from this commentary in their own ḥāshiya writings. In this context, it may be said that both al-Tībī’s Futūḥ al-ghayb and Chārpardī’s Tatimmat al-Kashshāf mark a turning point in the history of exegetical commentary (tafsīr sharḥ) in general, and in the reception of al-Kashshāf in particular.

There is much to be said about the intense scholarly labor invested by the editorial team—especially the critical editors—throughout the preparation process. But by way of a concluding remark, the following may suffice: In the 12th century, al-Zamakhsharī opened a remarkable new chapter in the Islamic intellectual tradition with his seminal tafsīr, al-Kashshāf. In the following century, Chārpardī read this monumental work with care, took detailed notes, and connected it to the broader tradition of Islamic scholarship, eventually composing his commentary under the title Tatimmat al-Kashshāf. In the 21st century, we, too, recognized the significance of Tatimmat al-Kashshāf, gathered and examined its manuscripts—perhaps for the first time in such a systematic manner—and brought the work to light through a rigorous critical edition based on challenging manuscript sources. As a result, a major obstacle has been overcome with regard to the re-reading, reassessment, and proper contextualization of this work within the classical tafsīr tradition.

References

Arıcı, Müstakim, “Reconstructing a Biography: Qāḍī Bayḍāwī, His Intellectual Networks and Works,” in Qāḍī Bayḍāwī in the Tradition of Islamic Knowledge and Thought, ed. Müstakim Arıcı, Istanbul: İSAM, 2017, pp. 23–103.

Bāghdādī Ismāʿīl Pasha, Hadiyyat al-ʿĀrifīn fī Asmāʾ al-Muʾallifīn wa-Āthār al-Muṣannifīn, ed. Kilisli Rifʿat Bilge, Ibn al-Amīn Maḥmūd Kemāl Ināl, Avni Aktuç, 2 vols., Istanbul: Millî Eğitim Basımevi, 1951–55.

Boyalık, Mehmet Taha, The al-Kashshāf Corpus: The Reception History of al-Zamakhsharī’s Tafsīr Classic, Istanbul: İSAM Publications, 2019.

Jamīl Banī ʿAṭāʾ, “al-Dirāsa,” in al-Tībī, Futūḥ al-Ghayb fī al-Kashf ʿan Qināʿ al-Rayb, ed. Iyād Aḥmad al-Ghawj et al., Dubai: Dubai International Award for the Qur’an, 1424/2013, vol. I, pp. 91–605.

Chārpardī, Ḥāshiyat al-Chārpardī ʿalā al-Kashshāf, Çorum Hasan Pasha Provincial Public Library, MS no. 3378.

Chārpardī, Tatimmat al-Kashshāf, Süleymaniye Library, Damad İbrahim Collection, MS no. 162.

|

M. Taha Boyalık He graduated from the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University. He completed his master’s thesis titled “An Analysis and Evaluation of the Introduction to Molla Fenârî’s Tafsīr Ayn al-ʿAyn” and his doctoral dissertation titled “ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī’s Theory of Syntax and Its Impact on the Tafsīr Tradition” at the Institute of Social Sciences of the same university. He conducted research as a visiting scholar at Duke University’s Department of Islamic Studies and the University of Amman. His primary research interests include Qur’anic exegesis (tafsīr), rhetoric (balāgha), linguistics, philosophy of language, and post-classical Islamic thought. Since 2011, he has been continuing his academic work at Istanbul 29 Mayıs University. In addition to his books “Language, Discourse, and Eloquence: ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī’s Theory of Syntax” and “The al-Kashshāf Literature: The Impact History of al-Zamakhsharī’s Tafsīr Classic”, he has authored numerous critical editions, translations, articles, and conference papers. |

M. Taha Boyalık

He graduated from the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University. He completed his master’s thesis titled “An Analysis and Evaluation of the Introduction to Molla Fenârî’s Tafsīr Ayn al-ʿAyn” and his doctoral dissertation titled “ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī’s Theory of Syntax and Its Impact on the Tafsīr Tradition” at the Institute of Social Sciences of the same university. He conducted research as a visiting scholar at Duke University’s Department of Islamic Studies and the University of Amman. His primary research interests include Qur’anic exegesis (tafsīr), rhetoric (balāgha), linguistics, philosophy of language, and post-classical Islamic thought. Since 2011, he has been continuing his academic work at Istanbul 29 Mayıs University. In addition to his books “Language, Discourse, and Eloquence: ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī’s Theory of Syntax” and “The al-Kashshāf Literature: The Impact History of al-Zamakhsharī’s Tafsīr Classic”, he has authored numerous critical editions, translations, articles, and conference papers.